In today’s post for free subscribers we’re going back to take another look at the books that cost more than your house.

Last week we talked a little about how these magnificent objects were made, and then covered a brief survey of the artistic styles. Starting with the Hiberno-Insular (Book of Kells and Lindisfarne Gospels) we touched on the Carolingian Renaissance (we’ll get back to this massively important turning point in more depth soon, promise) and Romanesque, leaving off with our toes hanging over the edge of the early Gothic.

Let’s dive in.

This post is free to all subscribers and readers.

The Sacred Images Project looks at art history and culture through the lens of the first 1200 years of Christian sacred art.

If you would like to accompany us into a deep dive into these spiritually and culturally enriching issues, to grow in familiarity with these inestimably precious treasures, I hope you’ll consider taking out a paid membership, so I can continue doing the work and expanding it.

This is my full time work, but it is not yet generating a full time income. I rely upon subscriptions and patronages from readers like yourself to pay bills and keep body and soul together.

You can subscribe for free to get one and a half posts a week. For $9/month you also get a weekly in-depth article on this great sacred patrimony, plus extras like downloadable high res images, photos, videos and podcasts (in the works), as well as voiceovers of the articles, so you can cut back on screen time.

We are significantly further ahead in the effort to raise the percentage of paid to free subscribers than we were a month ago, from barely 2% to just over 4.5%, but this is still well below the standard on Substack for a sustainable 5-10%.

The other way you can help support the work is by signing up for a patronage through my studio site, where you can choose for yourself the amount you contribute. Anyone contributing $9/month or more there will (obviously) receive a complimentary paid membership here.

You can also take a scroll around my online shop where you can purchase prints of my drawings and paintings and other items.

Like this painting I did last year illustrating the Psalm, “Quam dilecta” in the Greek iconographic style - egg tempera on a gilded ground.

How amiable are thy tabernacles, O Lord of hosts!

My soul longeth, yea, even fainteth for the courts of the Lord: my heart and my flesh crieth out for the living God.

And now, back to our show…

Gothic (12th to 16th century); A quick list of key characteristics:

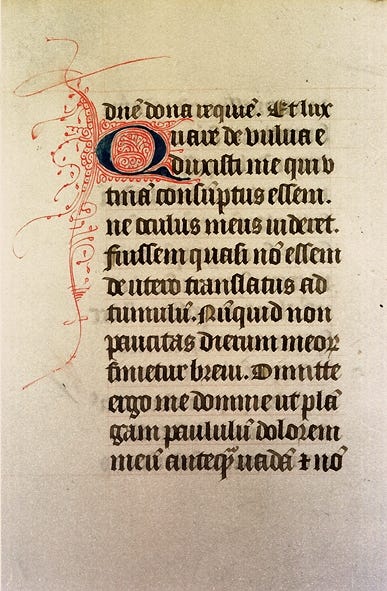

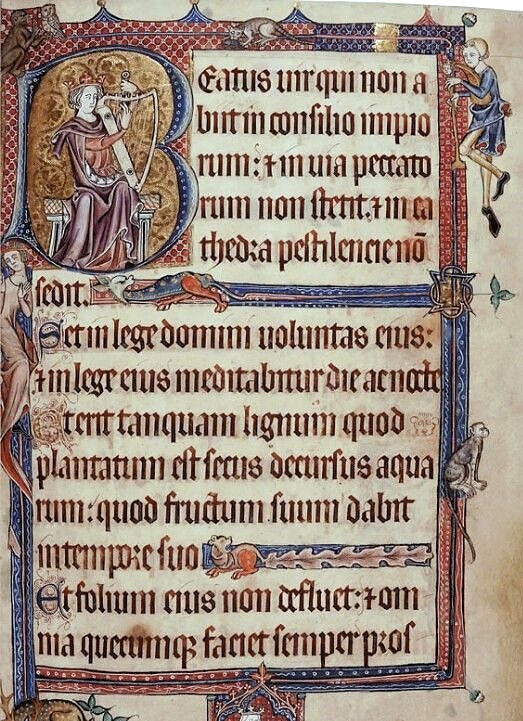

Gothic Script: Development of Gothic script (Textura), characterized by its dense and angular appearance.

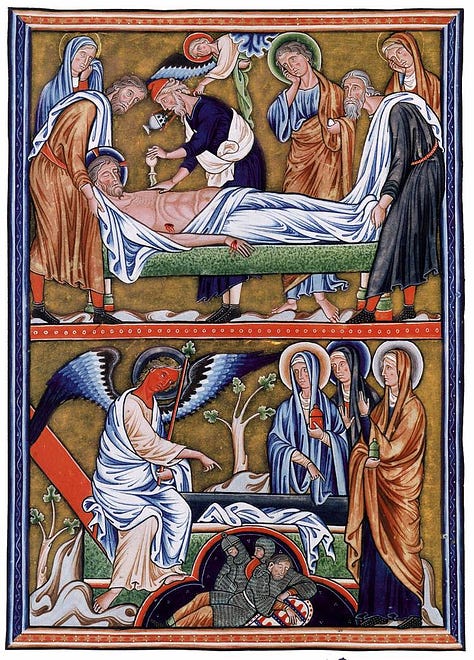

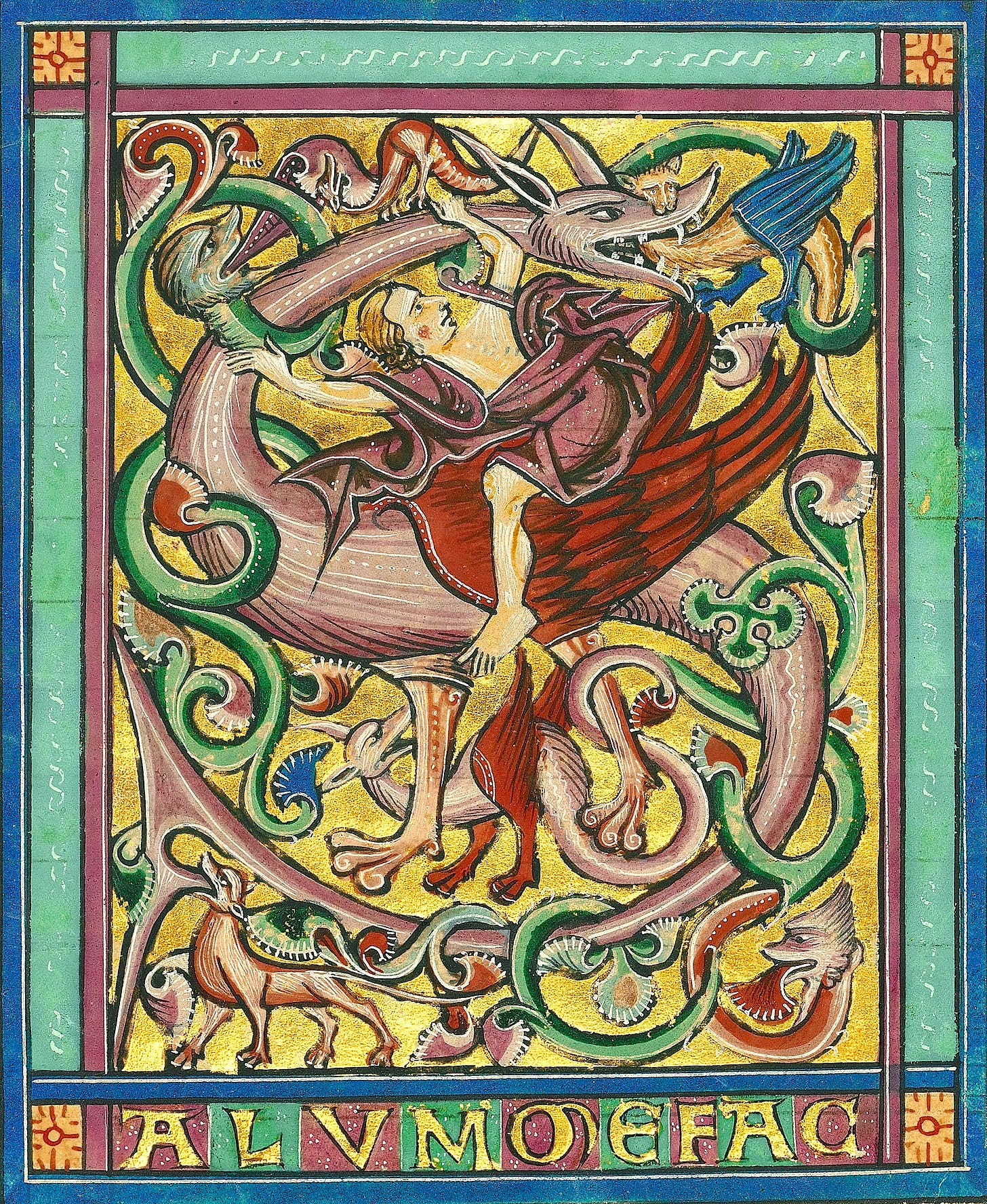

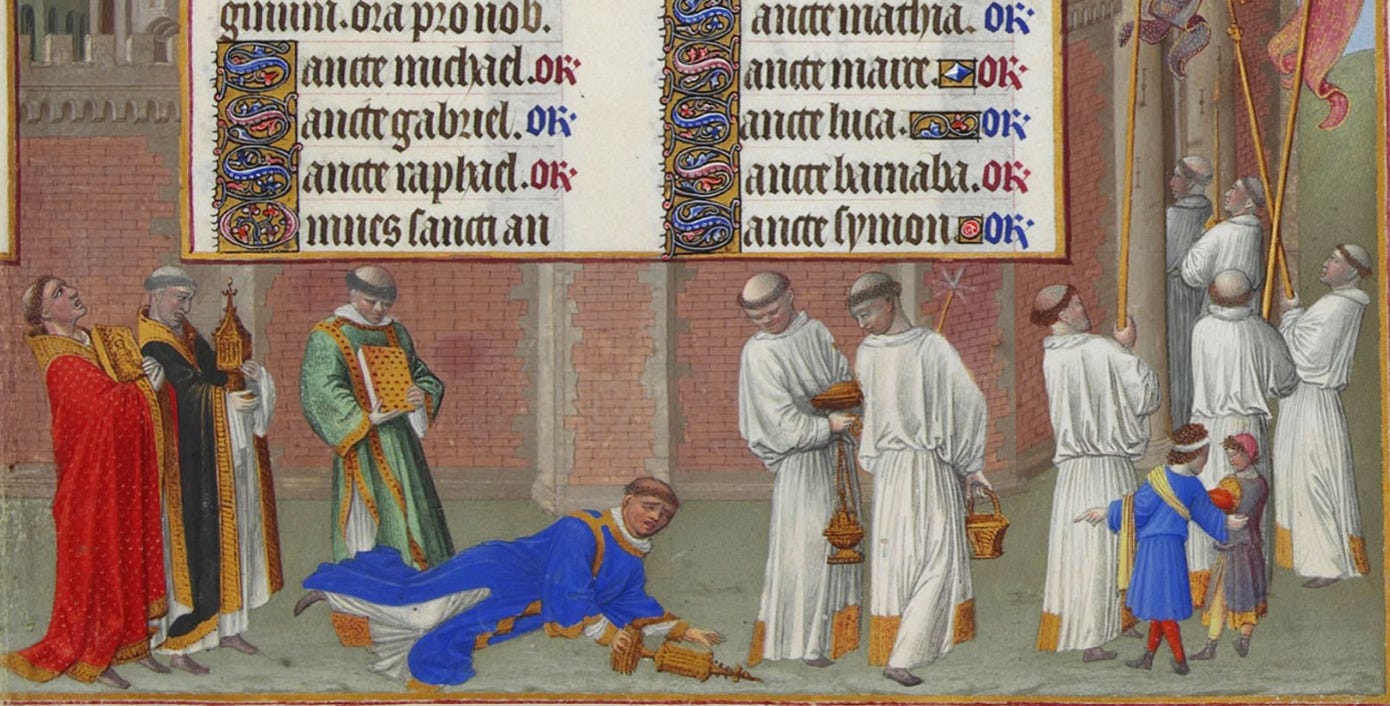

Elaborate Decorations: Increased complexity in decorations, including often whimsical and entertaining marginalia, historiated or decorated initials and full-page miniatures.

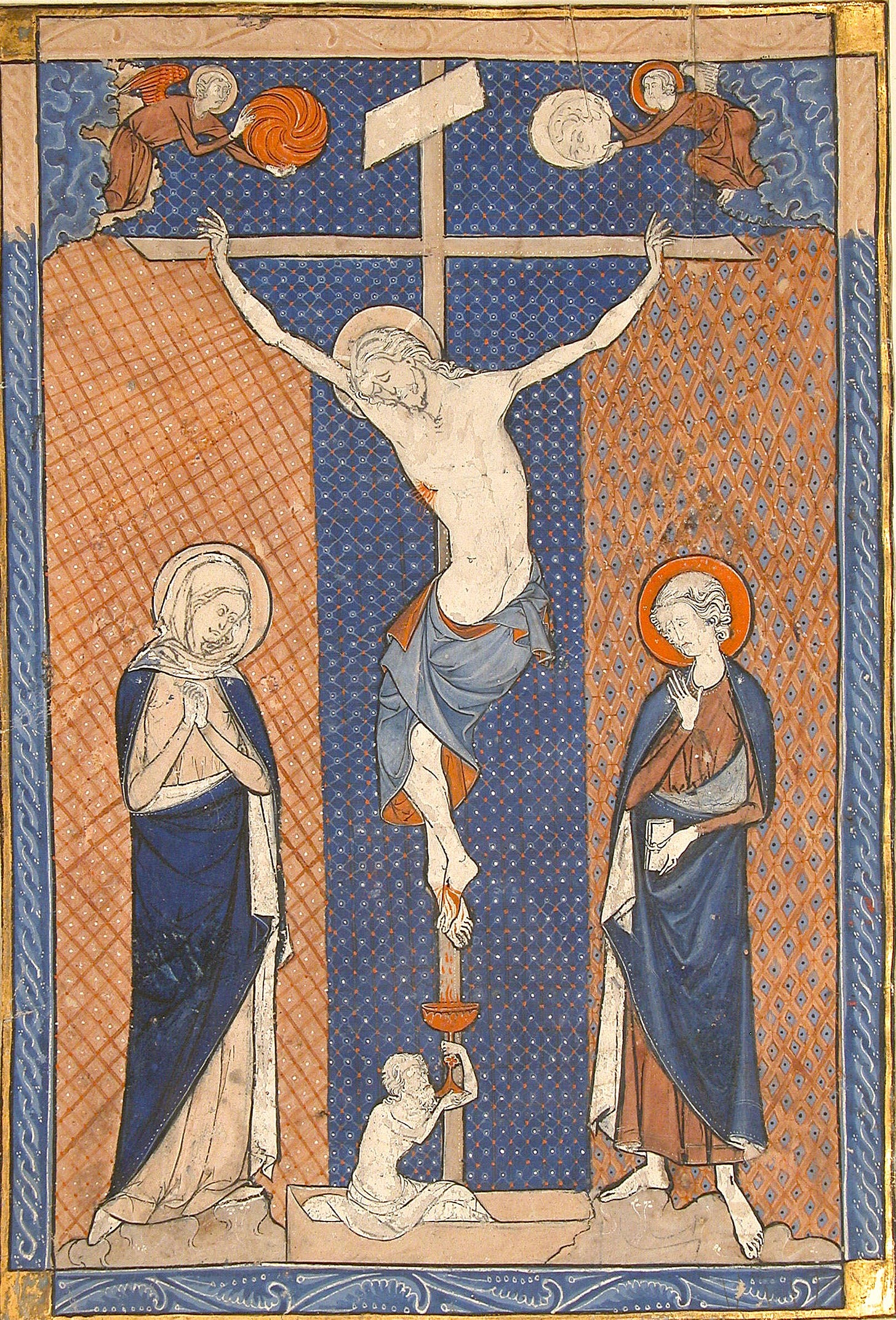

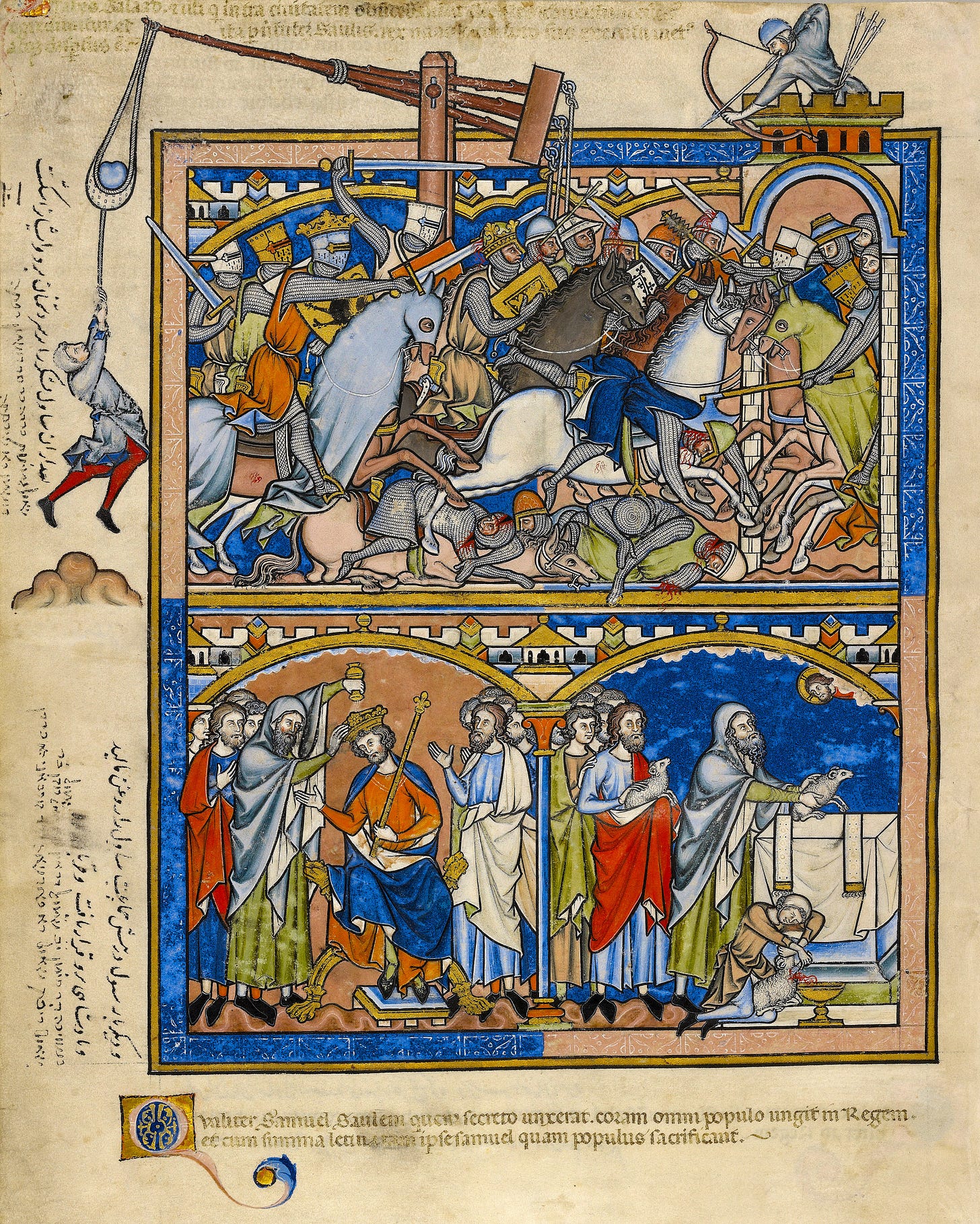

Naturalism: Greater naturalism and attention to detail in figures, draperies and landscapes, while still retaining fantastical and decorative elements.

Appearance of lay professional workshops: as literacy and wealth increased so did the demand for books from lay clients who commissioned Psalters and Books of Hours as luxury items

Key Examples: The Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, the Luttrell Psalter, and the Hours of Jeanne d'Evreux.

The Gothic period brought significant advancements in manuscript illumination, marked by the development of the Gothic script (called Textura) and a heightened naturalism in the illustrations.

The style spread across Europe, giving rise to the International Gothic style known for its elegance, elongated figures, and detailed backgrounds. Intricate craftsmanship and aesthetic sophistication defined Gothic manuscript art, which was often carried out by professional workshops of lay craftsmen, rather than monks.

In the images there was a growing emphasis on naturalism and detail, though the forms were often still fantastical.

Manuscripts from this long era featured lively, and often elaborate decorations, including marginalia, historiated initials, and full-page miniatures as well as textual embellishments like red pen flourishes. A direct stylistic line can be traced to Gothic painting from the original forms of Byzantine art that were spread everywhere by the continuation of the old Empire in Constantinople.

After the Byzantine - which is still going on today - the Gothic period is the longest period of sacred art continuity, and is the pinnacle of expressions of sacred art in the western tradition. It stretched from the 12th to the 16th century when it was finally supplanted everywhere by the Naturalism and Humanist movement that came out of central Italy, starting in the 15th century.

The creation of luxurious illuminated manuscripts, such as Books of Hours, became popular among wealthy secular patrons. The Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, the Luttrell Psalter, and the Hours of Jeanne d'Evreux exemplify the artistic achievements of the later Gothic period.

Gothic manuscript art also often displays a remarkable sense of fun and whimsy, reflecting the multifaceted nature of medieval culture. While the manuscripts are primarily known for their religious content, they also frequently include playful, humorous, and even fantastical elements.

Marginalia

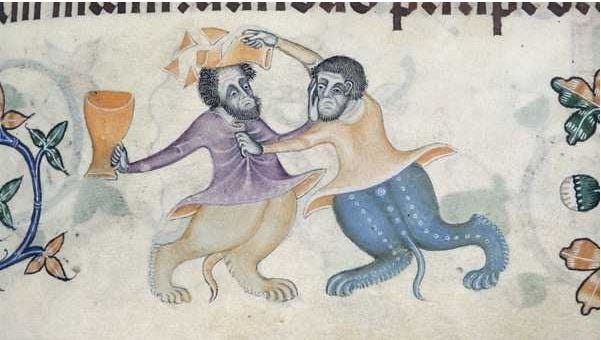

The part many people like best about Gothic manuscripts is the often hilarious margin figures of warrior bunnies, knights jousting with snails and foxes dressed as bishops. The margins of Gothic manuscripts often feature a variety of fantastical creatures and hybrid monsters. These imaginative beings reflect the medieval fascination with the strange and the marvellous.

Grotesques and drolleries are common in Gothic manuscripts. These often bizarre and exaggerated figures serve as a form of visual humour, entertaining the reader and showing off the artist’s creativity.

Gothic illuminators also enjoyed incorporating visual jokes and puns into their work. These could be quite subtle and clever, requiring the reader to pay close attention to catch the humour. For example, scenes might depict literal interpretations of proverbs or humorous reinterpretations of familiar biblical stories.

Animals behaving like humans appear frequently in Gothic manuscripts. These anthropomorphic animals often serve as parodies and satirical commentaries on human society and social norms.

Courtly Love and Secular Themes

While religious themes dominate Gothic manuscripts, many also contain secular content. These manuscripts might include scenes of courtly love, chivalric adventures, and festive activities, reflecting the lighter aspects of medieval life.

Books of Hours, popular among the nobility, often include both devotional texts and richly decorated calendars featuring scenes of daily life, seasonal country activities, and festivals. These illustrations provide a glimpse into the more joyous and celebratory aspects of medieval culture.

These are some exquisite examples! The artistry -- and the level of preservation on the manuscripts -- is truly stunning.

I love it when someone does the research you do (and not because it saves me the time!). Thank you so much for your effort!!