Iconographic heresy: an idea we need to get back

If you’ve been following this blog, you’ve been well introduced to the idea that Byzantine sacred art, and those forms that followed it in organic continuity from the Romanesque to the Gothic, is a kind of visual language. Its very particular use of line, form, value, space, colour, gesture etc., constitute the vocabulary of the language used to convey very specific theological ideas.

So what happens when those forms are used for ill, instead of good, to deceive, confuse or obfuscate that truth?

How does an icon teach and confirm Christian doctrine? And more to the point, how can that visual language be misused to convey ideas opposed to doctrine? What is a heretical icon, and can we find a use for this concept in the western tradition of sacred art?

Last week Anthony Visco, in an op ed for the journal of the Institute for Sacred Architecture, brought up a point that needs some more focus in the Rupnik situation. “It should not have taken his scandalous behaviour to see how problematic his art was.”

No, it certainly should not have, but how did that happen? How were Christians so easily duped, or more likely shamed into silence, told they couldn’t possibly understand his work? How has the modern artistic doctrine of visual indifference - a variety of moral relativism - come to dominate our thinking about sacred art?

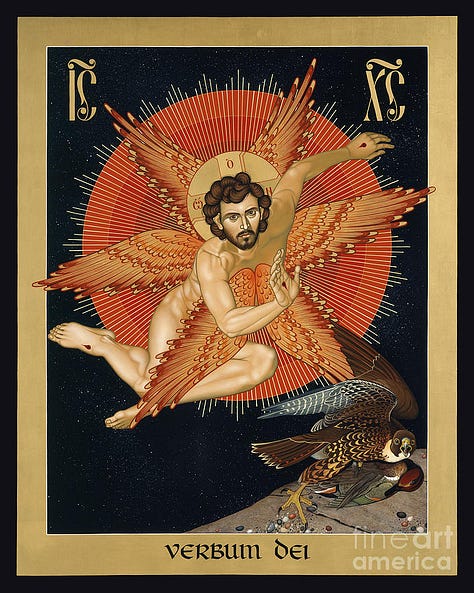

The director of the Atelier for the Sacred Arts in Philadelphia1 wrote in “Marko Rupnik: Modern Iconographer or Denier of the Incarnation?”:

Well before the alleged scandals became public, author Chris Moore made it clear that Rupnik’s works were not only ugly, but his repeated practice of painting a shared eye between God and man, a noticeable and prominent feature of his art, is theologically misleading. When used in Catholic art, this practice has always been reserved for representations of the three persons of the Trinity, where all three heads share the same eyes. But it has never been extended to another human.

When the logo was unveiled, Archbishop Salvatore Fisichella2, head of what was then-called the Pontifical Council for Promoting New Evangelization, declared that the shared eye of Christ and Adam represented the idea that “Christ sees with the eyes of Adam, and Adam with the eyes of Christ.3” Such an implication is likely why no orthodox iconographer has ever depicted such a merging. Rupnik takes what is sublime and distorts it, following contemporary culture while ignoring the artistic traditions of the Church.

But not being in that tradition himself, Professor Visco does not press the obvious conclusion that any Byzantine iconographer would not hesitate to make: that Rupnik’s art is simply heretical. If the idea that visual art can be orthodox or heterodox is new or surprising, it can only be because we have for centuries abandoned the real purposes of Christian sacred art.

So, let’s talk about that idea and see if we can shift our perspective back a little to something more in keeping with those ancient traditions, before that great continuity was broken in the Renaissance.

This is a post for paid members. Join us to start exploring these ideas.

The Sacred Images Project looks at art history and culture through the lens of the first 1200 years of Christian sacred art.

If you would like to accompany us into a deep dive into these spiritually and culturally enriching issues, to grow in familiarity with these inestimably precious treasures, I hope you’ll consider taking out a paid membership, so I can continue doing the work and expanding it.

This is my full time work, but it is not yet generating a full time income. I rely upon subscriptions and patronages from readers like yourself to pay bills and keep body and soul together.

You can subscribe for free to get one and a half posts a week. For $9/month you also get a weekly in-depth article on this great sacred patrimony, plus extras like downloadable ebooks, mini-courses, high res images, photos, videos and podcasts (in the works).

If you would like to set up an ongoing patronage for an amount of your choice, you can do that at my studio blog, Hilary White; Sacred Art, where you can also take a browse around my shop where I sell prints of my drawing and painting work and other items.

Icons as teaching instruments

So far in our discussions we’ve mostly emphasised the “spiritual conduit” idea, that an icon is a way of bringing heaven into the room with the viewer, or of erasing the distance between heaven and the viewer. We’re going to talk about that some more later, but in today’s post we’ll discuss the more prosaic use of icons, their didactic function.

In the Byzantine Christian tradition, icons are valued as didactic theological instruments intimately related to the liturgy. Sacred images serve as visual scripture, and are specifically called equal in importance to the Scriptures by the Second Council of Nicaea, AD 7874.

"The honour rendered to the image passes to its prototype, and whoever venerates an icon venerates in it the person depicted.”

Seventh Ecumenical Council (Second Council of Nicaea)

This authoritative doctrine affirms that the veneration of icons is intrinsically linked to the respect and honour given to the saints and the proper worship of God. Their abstract and symbolic representations of Christ, the Virgin Mary, saints, and biblical events visually confirm complex theological truths and moral teachings, making them tangible and immediate for the worshipper.

The didactic function of icons is rooted in the belief that they provide a “window into the divine,5” offering an immediate means to contemplate and engage with the sacred and heavenly realms. Icons are meticulously crafted according to theological guidelines to ensure accurate and orthodox representation of sacred subjects.

The use of specific iconographic conventions, such as symbolic colours, gestures, and compositions, reinforced doctrinal messages and aided in the memorization of scriptural and theological themes.

Iconographic heresy

All this makes it easy to understand why the Byzantine world is to this day sensitive and vigilant against the use of the iconographic language to depict error or even outright disinformation about the Faith - heresy.

For contemporary Byzantine iconographers, the concept of the “heretical icon” takes on new dimensions in light of the mass production of images and their rapid dissemination on the internet. Today, icons are often reproduced and shared without any theological oversight that traditionally guide their creation.

This proliferation of images, detached from the rigorous standards and spiritual discipline of the iconographic tradition, poses significant risks for the faithful. Inaccurate or distorted representations of holy figures and events can easily find their way into the homes and hearts of believers, leading them to embrace heretical ideas.

For Western Christians, the widespread availability of images that fall entirely outside Byzantine standards poses a significant risk, potentially even more so given our long separation from the iconographic tradition. Unlike the eastern Church, which has maintained a continuous and rigorous approach to iconography with ecclesial oversight, the western Church has no formal oversight on the output of painters and manufacturers of these images.6 In the Orthodox and Byzantine Catholic Churches a person becomes an iconographer only with the “blessing” or permission of the local priest or spiritual father. He undergoes training not only in painting techniques but in the theology of icons.

The long separation of the Great Schism, the radical break from the sacred art tradition that started at the Renaissance and the impact of the Third Iconoclasm of the Protestant Revolution has left western Christians with almost no surviving visual “sensus fidelium”. Our thousand-year long stretch of disasters has left us without the tools to recognise theological and doctrinal nuances of iconography.

Western Christians often encounter religious images through commercial and unregulated sources, which can lead to a fragmented and sometimes misleading visual theology. This is how we have the bizarre situation in which American and European neo-Baroque realist painters, working from the visual language of magazine photography and 19th century Academic style, are hailed as “traditional” by sincere believers whose knowledge of art history, coming from popular secular sources, stops dead at 1500 AD.

Iconographic ideological propaganda

To all this confusion, including the fracturing of western Christendom by the Protestant disaster, we must now add the confusion and obscuring of even fundamental Christian moral doctrines that have been rampant since the 1960s. We are in an age in which we hear, from the highest possible sources, that certain things we had thought sacrosanct are not, and that certain things we thought horrors and abominable mortal sins are morally acceptable.

Simply put, these are images that use the iconographic style to deliberately promote heresy and immorality, that laud and lionise as sacred heroes persons of abominable morality, who have worked to undermine the Faith and destroy the Church. Combined with modern methods of dissemination, they have amounted to an aerosolising of visual heresy and endorsements of moral depravity.

And this is common, even the norm, in western Christianity. This painter and others doing the same thing are themselves lionised, awarded and adulated in mainstream Catholic circles, given commissions and their works displayed everywhere. The Rupnik story is repeated endlessly in a Church at war with its own doctrine. The painters like Rupnik and Lentz are propagandists for a civil war that is at last coming to its final stages.

These are not images of the divine; they are images of hell.

How can we fix this problem?

The other day I got into an interesting discussion - not for the first time - about the problems we have with depicting the devotion of the Sacred Heart. Why are all the Sacred Heart devotional images so dreadful? Sickly sweet, maudlin, cloying to the point of nausea, with Christ depicted as effeminate and ineffectual? Someone in the Substack chat had asked if anyone knew of a Byzantine style depiction they could use to do the enthronement of the Sacred Heart at home.

I responded:

The problem with the visual material of the Sacred heart, the image, is that it is an exclusively Latin and modern devotion. It can be argued that it has roots back to the visions of St. Gertrude the Great (1256 –1302) but in practice it was popularised in the 1670s, long, long, LONG after the Latin Church had abandoned all its visual continuity with the sacred art tradition, and fully embraced Naturalism.

… So the problem faced by us today is that with the revival of serious spirituality - which I think the devotion to the Sacred Heart fits into - is almost completely bereft of visual representations […in keeping with the ancient tradition]…

We would like to just say, Oh, just do a Byzantine version of it, but that kind of fails to grasp how Byzantine art works. There's no Byzantine prototype for the Sacred Heart. So each individual painter is left to make it up for himself. And since there is no real conception in the western Catholic Church of iconography, what it is and is for and how it fits into our theological landscape, the results are not reliable.

The problems don’t come from having adopted this or that particular painting style. We adopted all these variations on naturalistic painting styles because we abandoned the theological purpose of sacred art. They come from having forgotten what sacred art is actually for. So I think the solution has to come by going back to the starting point and re-examining what we held, what the Church declared, about sacred images and their proper uses.

The Seventh Ecumenical Council 7declared for the whole, undivided Church, for all time:

“We define that the holy icons, whether in colour, mosaic, or some other material, should be exhibited in the holy churches of God, on the sacred vessels and liturgical vestments, on the walls, furnishings, and in houses and along the roads, namely the icons of our Lord God and Saviour Jesus Christ, that of our Lady the Theotokos, those of the venerable angels and those of all saintly people.

Whenever these representations are contemplated, they will cause those who look at them to commemorate and love their prototype. We define also that they should be kissed and that they are an object of veneration and honour (timitiki proskynisis), but not of real worship (latreia), which is reserved for Him Who is the subject of our faith and is proper for the divine nature, ... which is in effect transmitted to the prototype; he who venerates the icon, venerated in it the reality for which it stands."

We can thank the Rupnik scandals for one thing, the same thing we can thank the incredible extremes of the Bergoglian period for in general: it has alerted us to the shortcomings in our own system. We’ve gone a long, long time passively accepting the secular idea that the art in our Church is to be judged subjectively according to personal taste, so anything is acceptable to place above an altar.

The doctrinal revolutionaries who took control of the institution since the 1960s took advantage of that free-for-all situation and have used it to advance their heresies. But this situation is finally being taken seriously as a part of a larger problem; how do we start to restore what was lost?

We’re going to talk more about this in the coming weeks. In a conversation with a nice young American painter, we discussed the question, “How can we make a sacred art now that is in continuity with the great tradition, but at the same time is meaningful for western Christians in our time?” It’s important to take this as an opportunity to strike a blow more widely, to use this terrible situation to take some steps toward an authentic restoration.

Anthony Visco would doubtless vehemently disagree with one of the foundational thesis statements of this website, to wit, that the illusionistic naturalism that started in the Italian Renaissance to replace traditional Christian art, represented a radical break from and opposition to the ancient language and purpose of Christian art and has no place over a Christian altar; it cannot be considered true Christian sacred art. I do not endorse the training in those styles for sacred art.

I will never be able to see Fisichella’s name in print without stopping to remind readers that he had to be forcibly removed from his position as head of the Pontifical Academy for Life after he wrote a public letter endorsing abortion. It took two years of combined efforts of pro-life organisations around the world, the membership of the Pontifical Academy for Life, and finally a dossier of primary sources placed physically into the hand of the Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, to pry him out of his position. We need to keep in mind what kind of men are running the show in Rome.

In fact this is a quote from Rupnik himself, given in an interview about the design.

Convened to address the theological issues of the iconoclastic crisis.

A commonly used expression which isn’t exactly right, but will do for now.

This problem goes a long way back. The Council of Trent, despite the ravages of the Protestants against the artistic heritage of the Church and the advent of the printing press that would make heretical images widely available, had barely a vague paragraph or two on the subject, and said nothing definitive. The Church authorities have long since given up on sacred art, considering it a matter of no importance.

It is called the Seventh Ecumenical Council because it is the last of the councils of the undivided Church.

Outstanding. Well done Hilary.

I learned a lot today, Hilary, including your above response to Brittany. Thanks.