Mystery of Sacred Images: Understanding the Visual Language of Faith

Signs, symbols, prototypes and semiotics

I thought we’d change gears for today’s post for all subscribers, and talk about some basic conceptual framework topics. As we go forward in the historical narrative, if we’re going to understand what sacred images meant to our spiritual ancestors, we have to try to get into their heads a little. For the last few hundred years, we in the western world have had an intellectual culture based on materialism, which has given us a kind of flat-universe metaphysics. We live in a metaphysical framework in which visual things are simply images of things - light striking the retina having bounced off a physical object and creating an image in the brain - without any inherent higher meaning.

This materialist view has deformed how we approach art and symbols today. We’re used to thinking of images as just representations of physical reality, meant to document or entertain - but essentially to be single-level depictions of natural reality; simply, the world we can see. A lamb in a field is just a lamb in a field - a part of the background landscape to set the scene.

But for believers throughout the Christian centuries - and down into the deeps of the human past into our days painting cave walls with ochre and charcoal - visual symbols revealed truths beyond the physical world, acting as a bridge between physical and metaphysical reality, conveying realities that transcended the merely physical realm. Sacred art wasn’t merely decorative or illustrative. It wasn’t just to give an idea of what Christ might have looked like, essentially to entertain the visual imagination in the way of television or movies.

Understanding this visual language requires theological literacy, something even ordinary Christians from the earliest times were expected to cultivate. They were not only to be familiar with Scripture but also with the teachings of the Apostles and Fathers, who interpreted those Scriptures, but with the correct visual as well as verbal expression of these truths.

What we now call semiotics - the study of how signs and symbols convey meaning - helps us decode the connections between the visible elements of sacred art and the spiritual realities they signify. The “signifier,” such as a lamb, is connected to that which is “signified,” the meaning, which is Christ’s atoning sacrifice. Every element of sacred art, from the simplest symbol to the most complex composition, serves as a gateway to the truths of the faith.

If we’re going to make sense of this visual language, even of the idea of a “visual language” at all, we need to set aside modern - that is, materialist, utilitarian, Enlightenment - assumptions and approach these images as they were intended: as signs pointing to higher spiritual realities, and as conduits to bring those realities into the room.

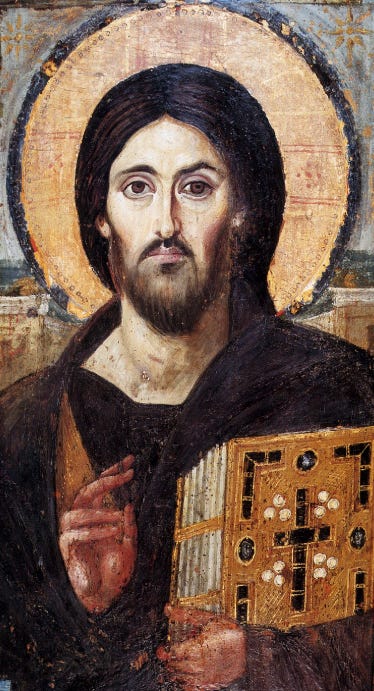

In today’s post for all subscribers, we’ll talk about the symbolic mindset, and lay down some groundwork ideas for understanding a visual language that is understood to be “visual theology.” We’ll explore iconographic prototypes, images so deeply rooted in tradition that they have become intangible cultural pillars, acting as templates not only for telling a story from the Bible or the lives of the saints, but shaping how we perceive and interpret spiritual realities, ourselves, God and the universe. These prototypes are not random; they are carefully crafted, maintained and refined over centuries to communicate theological truths, not merely historical accidents, connecting the seen and the unseen. Understanding them allows us to bridge the gap between our flat modern worldview and the rich, layered meanings sacred art holds for those who create and contemplate it.

At the Sacred Images Project we talk about Christian life, thought, history and culture through the lens of the first 1200 years of sacred art. The publication is supported by subscriptions, so apart from plugging my shop, there is no advertising or pop-ups. It’s my full time job, but it’s still not bringing a full time income, so I can’t yet provide all the things I want to and am planning for.

You can subscribe for free to get one and a half posts a week.

For $9/month you also get the second half of the third post, plus a weekly paywalled in-depth article on our great sacred patrimony. There are also occasional extras like downloadable exclusive high resolution printable images, ebooks, mini-courses, videos and eventually podcasts.

Sacred Art Shop

At the Met, I found this gorgeous painting by Bartolo di Fredi, a successor (after the Black Death) to the great Sienese masters Duccio di Buoninsegna and Simone Martini, and have created a standing masonite panel print from it.

I think it would make an elegant addition to a prayer corner or mantel.

You can order one here:

Signs, Symbols, Prototypes and Semiotics - what images mean

Semiotics is the study of how signs and symbols communicate meaning. It examines the relationship between a sign’s visible form - its signifier - and the concept or reality it represents, that which is signified. In the context of sacred art, semiotics helps us understand how visual elements, such as colours, shapes, and compositions, convey theological truths. For example, a lamb standing on a plinth is not just an animal; it signifies Christ as the Lamb of God from the Book of Revelation, sacrificed for the salvation of the world.

Sacred art relies on this layered communication to speak to both the mind and the soul, connecting the material and spiritual worlds. With this in mind, how do we know what a particular image “means”? How can we begin to learn the language?

This question lies at the heart of understanding Christian sacred art. We know an image of a lamb represents a lamb but what that lamb means or signifies is another question. The signs and symbols of sacred art, where meaning is layered, are sometimes subtle, and like any language always deeply tied to the spiritual and cultural context. It is rooted in the foundational elements of the Christian faith: Scripture and the Tradition of teaching - doctrine - that interprets and illuminates Scripture. These two pillars form the basis for the visual language of sacred art, ensuring that every image reflects and communicates revealed truths.

In the undivided Church, before the Great Schism that divided East and West, sacred images held a status equal in rank to Scripture and Tradition1. They were not merely illustrative; they were considered “visual theology,” carefully crafted and rigorously governed to ensure their faithful transmission of divine truth. In the ancient tradition of the Church, there is such a thing as “visual heresy.”

But more than this, an icon - in whatever form, whether a fresco, panel or mosaic - was taken as a kind of interface where a viewer could be in direct communication with the persons and realities depicted. This mystical operation of iconography has been almost entirely lost in the western Church.

Prototypes and canonicity

The concept of the prototype in Byzantine iconography carries a double significance and is crucial to understanding what Christian sacred art is and is not. On the one hand, it refers to the standardised visual motif or established template used to depict figures, scenes, or events. As visually literate Christians, we know at a glance everything that is depicted in the image. At the simplest level, we know who these people are, and what they are doing.

Christian sacred art relies on “prototypes,” which term served a dual purpose. In one sense, a prototype was the established visual template for depicting a figure or scene, ensuring consistency and theological accuracy across generations.

Deposition of Christ/Descent from the Cross - a prototype

For example, every canonical depiction of the Deposition from the Cross, as we’ve seen above, always had the same elements and basic composition, regardless of the style of painting. We see the Virgin receiving the dead body of her Son, kissing either His hands or face, as He is taken down from the cross by Joseph of Arimathea, the nails in His feet removed by pincers by a figure who is assumed to be Nicodemus. The mourning Mary Magdalene and other women and St. John are usually present.

These particular figures, presented in this particular composition, constitute a canonical iconographic prototype.

We use the term “canonical” - from the Greek kanon (κανών), a “ruler,” “measuring rod,” or “standard” - to say that the icon is created according to the established rules and traditions of the Church, ensuring its fidelity to theological truths. A canonical icon adheres to the principles that govern sacred art, including its composition, use of symbols, and representation of figures, that transmit divine realities accurately.

Now, this isn’t to say that there are any official councils or Church documents laying out exactly how an icon of the Virgin should be painted - a very Latin Catholic idea2. Christian iconography is a living tradition, transmitted organically through the work of generations of iconographers, guided by the liturgical and theological life of the Church, who faithfully adhere to established prototypes, compositional rules, and theological principles.

This ensures that every icon is at the same time not merely a product of personal creativity or the iconographer’s personal ideas, but also not a mere slavish copy of previous works. It is a continuation of the Church’s visual language, grounded in the shared experience of faith, and expressed by a faithfully believing, living person, the painter.

Prototype and Hypostasis - the person depicted is present

When we use the term prototype, we mean not only the canonical image, but the original reality depicted - the person.

He who venerates the icon, venerates in it the reality for which it stands.

The Seventh Ecumenical Council declared for the whole, undivided Church, and for all time:

“We define that the holy icons, whether in colour, mosaic, or some other material, should be exhibited in the holy churches of God, on the sacred vessels and liturgical vestments, on the walls, furnishings, and in houses and along the roads, namely the icons of our Lord God and Saviour Jesus Christ, that of our Lady the Theotokos, those of the venerable angels and those of all saintly people.

Whenever these representations are contemplated, they will cause those who look at them to commemorate and love their prototype. We define also that they should be kissed and that they are an object of veneration and honour (timitiki proskynisis), but not of real worship (latreia), which is reserved for Him Who is the subject of our faith and is proper for the divine nature, ... which is in effect transmitted to the prototype; he who venerates the icon, venerated in it the reality for which it stands."

We often see the expression, “windows into heaven” used to describe icons, but this idea isn’t used by iconographers themselves without some hesitation.

The Greek contemporary iconographer, George Kordis, often uses the term “hypostasis” when talking about how an icon makes the person depicted present to the viewer. For Kordis the icon isn’t a window through which we look; it’s a personal encounter with a heavenly reality - a person.

This term can be confusing to western Christians who have lost most of the theology that underlies our artistic traditions.

For the idea that governs Byzantine (and patristic) thought is that of communion, which presupposes the voluntary meeting of hypostases, or persons, in a relationship of love. In this way a form must also have inner and external movement in order that it might express and reflect this vision of life.3

Elsewhere he writes:

Painting concerns the surface (epiphaneia) of objects. The epiphaneia, however, is not simply a surface, nor is it a vacuum or an empty space. Rather, in Byzantine art the epiphaneia is the manifestation of the hypostasis of the depicted object, which is at once both revealed and hidden. Indeed, its existence is revealed while its essence remains hidden.

The Greek word hypostasis, meaning “substance,” “foundation” or “underlying reality,” - when referring to a human being, it means the “person” in full - and is often used in reference to the images on icons. In Christology4, hypostasis is used to describe the Second Person of the Trinity, Jesus Christ, as a unique and distinct person within the Godhead.

This concept ties closely to iconography because an icon is not intended to show the mere superficial physical appearances, but the full reality of the person. The icon points directly to the living reality of the prototype it portrays. When it is an icon of Christ, since it depicts the whole person, the hypostasis, and not just the material appearances or “accidents,” it must not merely depict His humanity (or still less only His divinity) separately. The unity of the hypostatic union cannot be separated if the icon is to depict the full reality of Christ.

All of which is why to an iconodule - a person who embraces the Church’s ancient tradition of Christian sacred images in its full spiritual implications - the icon doesn’t merely depict the person, it brings the person into the presence of the viewer - more than a window.

Just as Christ promises to be present to the person calling upon Him in prayer, using His name, so the icon’s faithful depiction of His sacred face and person, becomes a means of His presence. The icon is offering a tangible connection to Christ Himself. Through the faithful veneration of His image, believers enter into a prayerful encounter with the living Lord, who is made present through the mystery of the icon.

Sacred art isn’t just decoration or storytelling, it’s not about providing instruction for the illiterates of previous ages; it is a living part of the Church’s Tradition. By engaging with it, we step into a world where the seen reveals and makes present the unseen in a communion of love between persons. Through the language of signs, symbols, and prototypes, sacred art we enter into true contemplation of divine mysteries, bridging the gap between the earthly and the heavenly.

Though there is some evidence that the iconographic framework was already being lost in the west as early as Charlemagne.

It’s been tried, mainly in the Russian Orthodox church, and found wanting as a method of ensuring the survival of the tradition.

There isn’t any other iconographer working today whose online courses I’d recommend more strongly than his.

We’ve mostly only heard the term in connection to the Hypostatic Union, defined at the Council of Chalcedon in 451: in the one person (hypostasis) of Jesus Christ, two natures - divine and human - are fully united without confusion, change, division, or separation. This means that Christ is fully God and fully man, perfectly and indivisibly united in a single person.

Artists “tinkering” with Sacred Art seems similar to “tinkering” with the Gospels. In the West it seems both have become acceptable. One can see a modern western portrayal of a Saint and have no idea who is depicted. The same cannot be said of an eastern portrayal of a Saint.

The Sinai Pantocrator is a wonderful icon, and very illustrative of your point about visual theology. Last year, a family came to my Orthodox church for the first time, and has since become catechumens (hopefully to be chrismated / baptized in soon). As they gradually came to understand the Orthodox theology as expressed in icons they (like many converts) began to bring icons into their home. The husband wanted a Pantocrator for their icon corner, but said at the time he was "creeped out" by the Sinai one, and wanted something more familiar (I run my church's little store, and said I'd see what I could stock). Well, this past Christmas they bought... a copy of the Sinai Pantocrator! I asked why the change - the husband said "I love His face in that icon. I get it now."