Sanctification in photos: St. Charles de Foucauld

"Faith strips the mask from the world and reveals God in everything"

“The moment I realized that God existed, I knew that I could not do otherwise than to live for him alone . . . Faith strips the mask from the world and reveals God in everything. It makes nothing impossible and renders meaningless such words as anxiety, danger, and fear, so that the believer goes through life calmly and peacefully, with profound joy- like a child, hand in hand with his mother.”

― St. Charles de Foucauld

I was working all day today on a big post about the differences in mindset between iconographic art and western naturalistic sacred art, iconographic prototypes and what it all means in relation to the Incarnation... But as it turns out it’s a pretty big subject, and I could feel my brain getting sucked down a gigantic rabbit hole with no bottom. So, I’ve decided to pivot and just do something simple and uplifting for this week’s Wednesday free post, and will keep working on the other thing, since it’s interesting and important. But for now, let’s talk about one of my favourite modern saints.

You didn’t think I had a favourite modern saint, did you.

The biography of Charles de Foucauld is one of the most remarkable stories of spiritual transformation we know of in the modern era. When I first heard of him, it was from a book titled “Modern Saints” - volume one or two, I can’t remember - that played a significant role in my return to the practice of the Catholic Faith in the late 1990s.

This post is free in full for all subscribers.

If you would like to accompany us into a deep dive into these spiritually and culturally enriching issues, to grow in familiarity with these inestimably precious treasures, I hope you’ll consider taking out a paid membership, so I can continue doing the work and expanding it.

You can subscribe for free to get one and a half posts a week. For $9/month you get a weekly in-depth article on this great sacred patrimony, plus extras like downloads, photos, videos and podcasts (in the works), as well as voiceovers of the articles, so you can cut back on screen time.

We are significantly further ahead in the effort to raise the percentage of paid to free subscribers than we were a month ago, from barely 2% to just over 4%, but this is still well below the standard on Substack for a sustainable 5-10%.

Today’s featured drawing is “Christus Patiens”. Graphite on paper. You can order a high quality art print of it and other items at my shop.

You can also set up a monthly patronage for an amount of your choice. Anyone starting a patronage for $9/month or more will get a complimentary paid subscription here.

Charles’ extraordinary conversion story caught my attention because it was so unlikely, so obviously an instance of Road-to-Damascus divine intervention it seemed almost hard to believe. It was the kind of story one usually associates with other, more miraculous ages, like that of Moses the Black, the criminal who became a Desert Father in the 4th century.

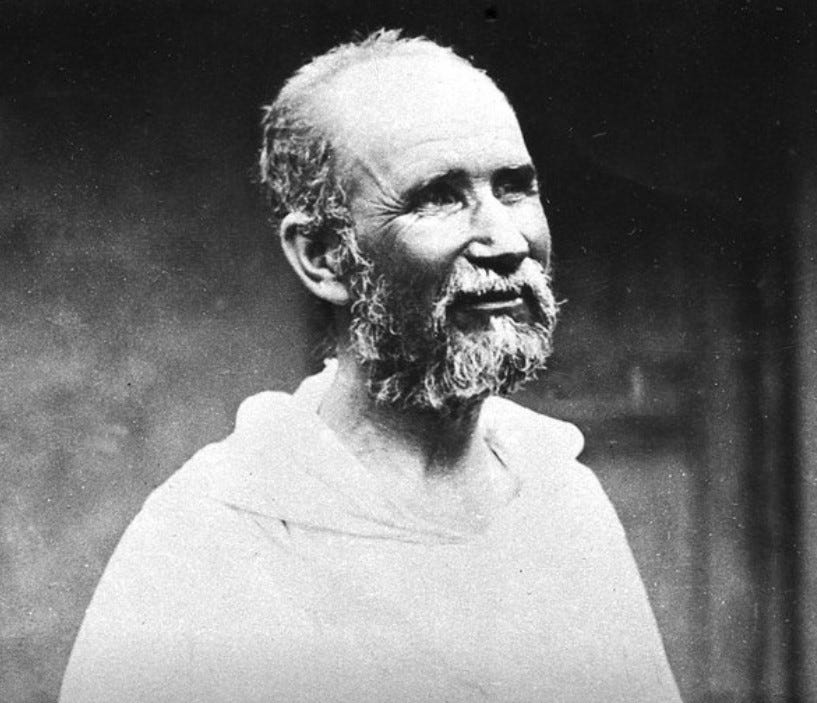

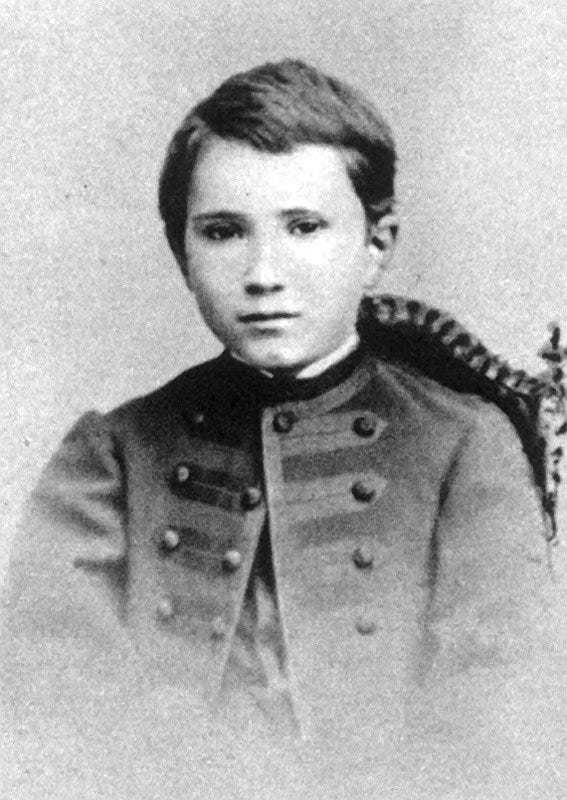

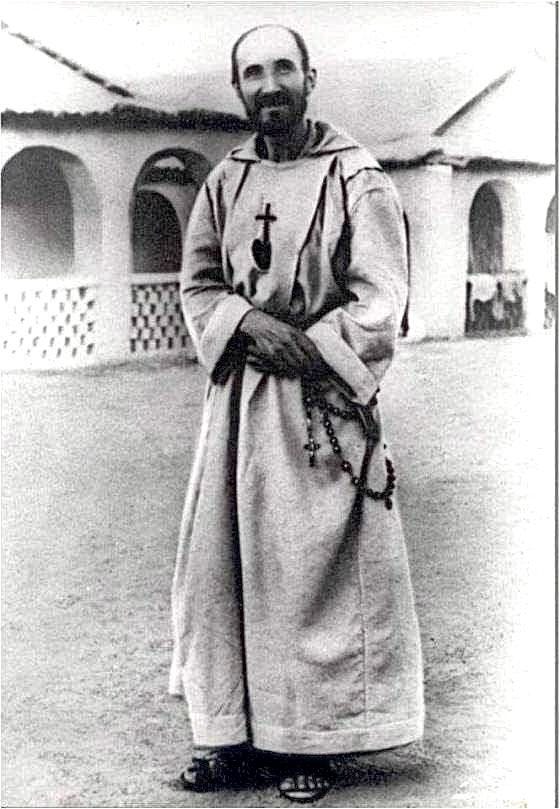

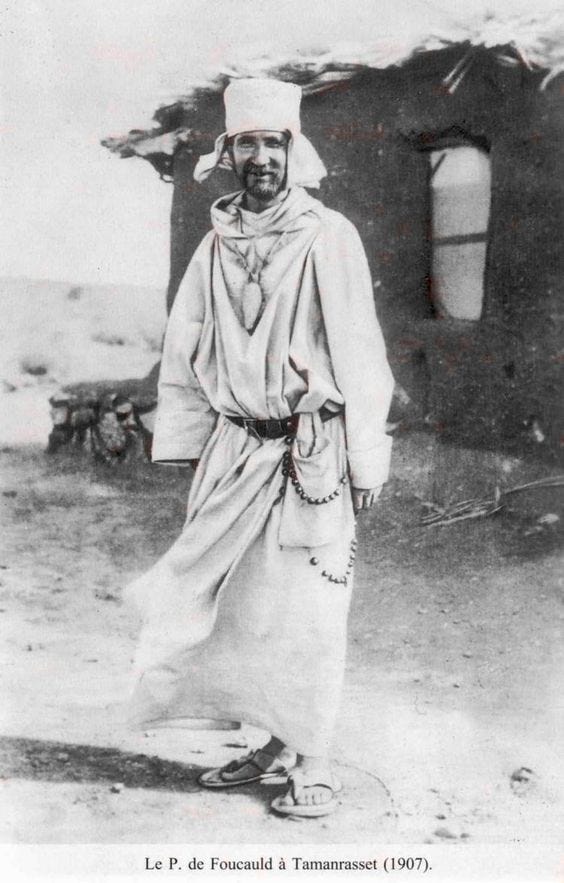

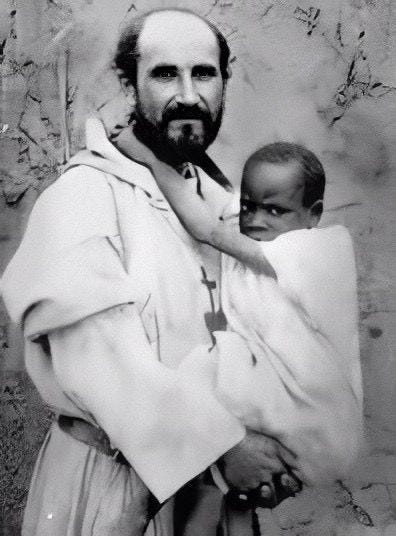

But what made his story even more eye-catching was the series of photographs of each stage of his life that we have. The thing that struck me was that you could literally see the transformation in his face. Since starting with iconography I’ve wanted to do a series of portraits of him in a semi-naturalistic and semi-iconographic style, based on some of these photos. I’ve long been meaning to share them here on this site.

And of course, I’m not the only one. So, here’s a post just about this wonderful story, with lots of pics, both photos and icons in various styles.

I think his story is so compelling because it seems to mix the prosaic materiality of modern life, with which was are all only too familiar, and the kind of almost fairytale atmosphere that comes with the ancient stories of the great saints and their miracle-filled lives. We are tempted by everything we see to think that there is no way out of the dull cinderblock-and-florescent-lights labyrinth of Modernia, that this lifeless, meaningless and sterile world is all there is. But here was a man who knew and lived in the centre of that same dystopia that we do, who opened a door and found something miraculous.

Early Life and Military Career

Charles Eugène, vicomte de Foucauld was born on September 15, 1858, in Strasbourg, France. He was baptised Catholic, and his family held deep religious convictions. However, Charles’ early life was tumultuous. By the age of six, he had lost both of his parents, and he and his sister were taken in by their maternal grandfather, Colonel de Morlet.

The colonel's strict and disciplined approach to upbringing contrasted sharply with the trauma and loss Charles had experienced, contributing to his early rebelliousness.

"I lived the way it is possible to live once the last spark of faith has been extinguished. I am bored to death."

Charles embarked on a military career, entering the prestigious Saint-Cyr Military Academy in 1876. Known for its rigorous training and high standards, Saint-Cyr was intended to prepare future officers for leadership roles in the French Army. Despite his intelligence and potential, Charles’ time at Saint-Cyr was marked by a lack of discipline and a penchant for the pleasures of life. One of his superiors wrote, “Being very young, this officer lacks firmness and enthusiasm. Of undeveloped character, he has much work ahead before he can perform at the level expected.”

He graduated in 1878, but his conduct, characterized by indulgence and defiance, soon led to career difficulties. He left Saint-Cyr ranked 333rd out of 386 and entered the Saumur cavalry school, from which he left dead last, 87th out of 87.

“I sleep for a long time. I eat a lot. I think little.”

After graduation, Charles was assigned to a regiment in Pont-à-Mousson, but his lack of discipline persisted. He was appointed second lieutenant in the 4th Hussars. Living in cohabitation, he wanted his partner to follow him when his regiment was sent to Algeria in 1880. There, this situation clashed with the Catholic hierarchy and he was ordered to separate from her, which he refused to do.

His indulgent lifestyle led to his dismissal from the army in 1881. However, he was soon reinstated due to the influence of his family and connections, which allowed him to join the 4th Chasseurs d'Afrique, a light cavalry regiment stationed in Algeria.

In Algeria, Charles’ behaviour initially did not improve. He continued to live a life of excess, which eventually led to a scandal. He left the army in 1882, choosing to explore North Africa rather than return to France in disgrace. This marked the beginning of a significant turning point in his life.

Expedition to Morocco and Search for Meaning

In 1883 in the sultan's lands the European could move freely and without danger, but in the rest of Morocco he could not enter unless disguised and putting his life in danger: he was seen as a spy and, if he were recognized, he would be massacred. Almost all of my travel took place in the independent part of the country. I disguised myself starting from Tangier in order to avoid embarrassing recognition. I passed myself off as a Jew. During the trip my clothing was that of the Moroccan Jews, my religion was theirs, my name was Rabbi Giuseppe. I prayed and sang in the synagogue, the parents begged me to bless their children…

Travel diary

The turning point in Charles’ life came during an expedition to Morocco in 1883-1884. Disguised as a Jewish rabbi, and accompanied by Mordochée, an authentic rabbi of Algiers and correspondent of the Société de Géographie de Paris, he journeyed through dangerous and remote regions forbidden to Europeans, meticulously documenting his travels. He was later awarded a gold medal for this expedition by the Geographical Society of Paris.1

His experiences in Morocco profoundly affected him, particularly the devoutness of the Muslim population. Their faith and devotion planted the seeds of spiritual curiosity in Charles, who began to question his own lack of belief.

Returning to France, Charles experienced profound inner turmoil. The death of his beloved grandfather in 1886 left him emotionally adrift, further fuelling his search for meaning. It was during this time that he reconnected with his Catholic roots, influenced by the pious example of his cousin, Marie de Bondy.

“At the beginning of October of the year 1886, after 6 months spent with my family in Paris, while I was having the writings of my trip to Morocco printed, I found myself with some very intelligent, virtuous and Christian people; at the same time I felt a strong interior grace within me that pushed me: I started going to church, without being a believer, I didn't feel comfortable except in that place and I spent long hours there continuing to repeat a strange prayer: ‘My God , if you exist, let me know you!’"

Conversion and beginning of religious life

Charles’ conversion was neither sudden nor simple. It culminated in a dramatic moment in October 1886 when, on the advice of Abbé Henri Huvelin, he made a confession at the Church of Saint Augustine in Paris, and received Communion.

“I then turned to Abbot Huvelin. I asked him for religious lessons: he ordered me to get on my knees and confess, to go and receive Communion right away ...

“If there is joy in heaven over a sinner who converts, there certainly was when I entered the confessional!”

This marked the beginning of a new chapter in his life, as he embraced the Catholic faith with fervour.

After being made to wait three years by his confessor Abbe Huvelin, Charles joined the Trappist monks in 1890, first in France and then in Akbes, Syria and stayed for seven years.

“My soul is experiencing a profound peace, which grows daily. It increases faith, which calls for gratitude. I am where the good Lord wants me to be. In a year, I shall make my profession. In my heart, I long to be bound through those vows, but I am already bound through my most every wish.”

Letter to his sister

Seeking Solitude and Service in Nazareth

Seeking a life of greater solitude and deeper connection with God, Charles left the Trappist order in 1897. He travelled on foot to the Holy Land, settling in Nazareth, where he lived as a hermit, working as a gardener and handyman for the Poor Clares, living in a shed on their property, aiming to emulate the hidden life of Christ, as a servant.

"Our entire life, in fact, ought to be one of imitation; it ought to be an imitation of Jesus by the humble and poor life we lead and by the laborious work we do."

Charles' time in Nazareth was also filled by intense periods of prayer, meditation, and contemplation. He would spend hours in adoration before the Blessed Sacrament, seeking to deepen his relationship with God.

Walking to Jerusalem

“After having spent Christmas 1888 in Bethlehem, having listened to midnight Mass and received Communion in the Holy Grotto, after two or three days I returned to Jerusalem. The sweetness I felt praying in that cave, where the voices of Jesus, Mary and Joseph had resonated, was unspeakable.

“I want to lead the life that I glimpsed, perceived walking through the streets of Nazareth, where Our Lord, a poor craftsman lost in humility and darkness, rested his feet…”

While residing in Nazareth, Charles made several pilgrimages to Jerusalem. These journeys were deeply spiritual, allowing him to walk in the footsteps of Christ.

In Jerusalem, Charles continued his humble existence, staying at various monasteries and religious houses, doing manual labour and dedicating himself to prayer.

During his time in the Holy Land, Charles wrote reflections and meditations that reveal a deepening understanding of his vocation. Charles’ writings from Nazareth and Jerusalem include numerous prayers, meditations, and reflections on the life of Jesus.

“My rule is so closely linked to the cult of the Holy Eucharist that it is impossible for many to observe it without there being a priest and a tabernacle; only when I become a priest will it be possible to have an oratory around which to gather and only then will I be able to have some companions...”

These writings would later form the foundation of his spiritual legacy and influence the religious communities that emerged after his death. They would later guide him as he embarked on his mission to serve the Tuareg people in Algeria and to begin to hope to found a religious community.2

“My place is in the desert. To establish myself over there, to be a priest and a hermit, for I believe that would be to the great glory of God, even if I remained alone…”

Mission in the Sahara

“Knowing from experience that no people are more abandoned than the Muslims of Morocco, of the Algerian Sahara, I asked for and obtained permission to come to Béni Abbès, a small oasis in the Algerian Sahara on the border with Morocco.”

In 1901, Charles returned to France and was ordained a priest and chose to settle in the Algerian Sahara, where he encountered slavery for the first time. The military built him a small dwelling of mud bricks that included a chapel. He began to befriend the local people, who he was pleased to learn called his hermitage “the brotherhood.”

Charles felt a deep calling to serve the Tuareg people, a nomadic Berber group living in the central Sahara. In 1905, he moved to the Hoggar region in southern Algeria, settling in the town of Tamanrasset.

Charles immersed himself in the Tuareg language and culture, becoming proficient in Tamasheq, the Tuareg language. He compiled an extensive Tuareg-French dictionary and wrote detailed ethnographic studies about their customs, poetry, and way of life. Volumes of his own poetry in Tamasheq have been published. His scholarly work earned him respect among the Tuareg and provided valuable insights into their society.

The hermitage became his base for his missionary work. His daily routine involved long hours of prayer, manual labour, and study. He celebrated Mass, provided medical assistance, and offered hospitality to travellers and locals.

Charles' approach to evangelism was through example rather than preaching. He believed in demonstrating the love of Christ through his actions, hoping that his life of service would inspire others.

“At the moment I am nomadic, I go from one camp to another, trying to create relationships of familiarity, of friendship... This nomadic life has the advantage of making me meet many people, of making me visit the region...

“Today I feel the joy of placing – for the first time in the land of the Tuareg – the Holy Eucharist in the Tabernacle.”

But though he begged the Lord for the rest of his life to send others to tend to the spiritual needs of the Tuareg people, none were ever able to come.

“I am always alone, many send me to say that they would like to join me, but there are difficulties, the main one being the ban placed by the civil and military authorities on all Europeans from moving in these regions, due to the insecurity.”

Death

On December 1, 1916, Charles de Foucauld was tragically killed by a band of raiders during a local uprising. He was attacked outside his hermitage in Tamanrasset, marking the end of his earthly mission. His death was a martyrdom, reflecting his ultimate sacrifice for the people he served.

Despite his relatively solitary and obscure life, Charles de Foucauld’s legacy grew significantly after his death. His writings, spiritual insights, and example of living a life of radical faith and love inspired the formation of several religious communities.

Pope Benedict XVI beatified Charles de Foucauld on November 13, 2005, recognizing his profound spiritual journey and enduring impact. He was canonized as a saint by Pope Francis on 15 May 2022 in Rome.

Some sources for more reading:

Spiritual family, Charles de Foucauld

"Charles de Foucauld" by Jean-Jacques Antier

“Heroes of God” by Henri Daniel-Rops.

Every child is born with a God-given grace and gift. Many of us are searching to learn it. Few discover it and fulfill it.

Excellent piece. Thanks for writing and sharing it.