Saturday Post: Japanese watercolours, "Nihonga"

It's Sunday. Let's look at some pretty pictures together

I know; it’s Sunday. Yesterday - in keeping with our ongoing agreement - I started writing a complicated thing about art and the meaning of life and whatnot, but of course it got bogged down and I got tired and went to bed. I’ll have to just accept that writing twice a week doesn’t mean publishing on those days.

So, that Deep and Important post is coming. Meanwhile, let’s have a nice Sunday afternoon or evening together just looking at some Japanese watercolour art. Why not?

First I’d like to pause and thank the people who signed up for subscriptions, donations and to be ongoing patrons through my studio blog:

In a single day a bunch of my financial worries have been relieved by your generosity. It’ll tell you how low my expenses are now, living in the Umbrian boonies, that the US $250 of recurring monthly patron contributions - most of which were about $10-40 - has covered my rent-plus-a-bit. I’m more grateful than I can express.

Learning how to do this work takes up a huge section of my CPU space, and the mental energy that was expended figuring out how to keep a roof over my head can now be redirected back to the work.

Several one-time donations were also greatly appreciated. Altogether a lot of pressure has gone in the last day. The readership of both sites also grew, with about 25 new subscribers to World of Hilarity and several more to the studio blog. Thanks especially to everyone who re-tweeted and shared on Facebook.

I’m working out how to create a Substack Chat for patrons. It involves putting the Substack App on your phone and then I add names into the Chat form and we can pass notes in class. I thought it would be fun to talk about art and life and faith between ourselves a bit. Maybe send along daily photo-posts of art I’ve found around about. I’ll be sending out an email soon to those who have contributed. It’s totally up to you if you want to sign on. And thanks again.

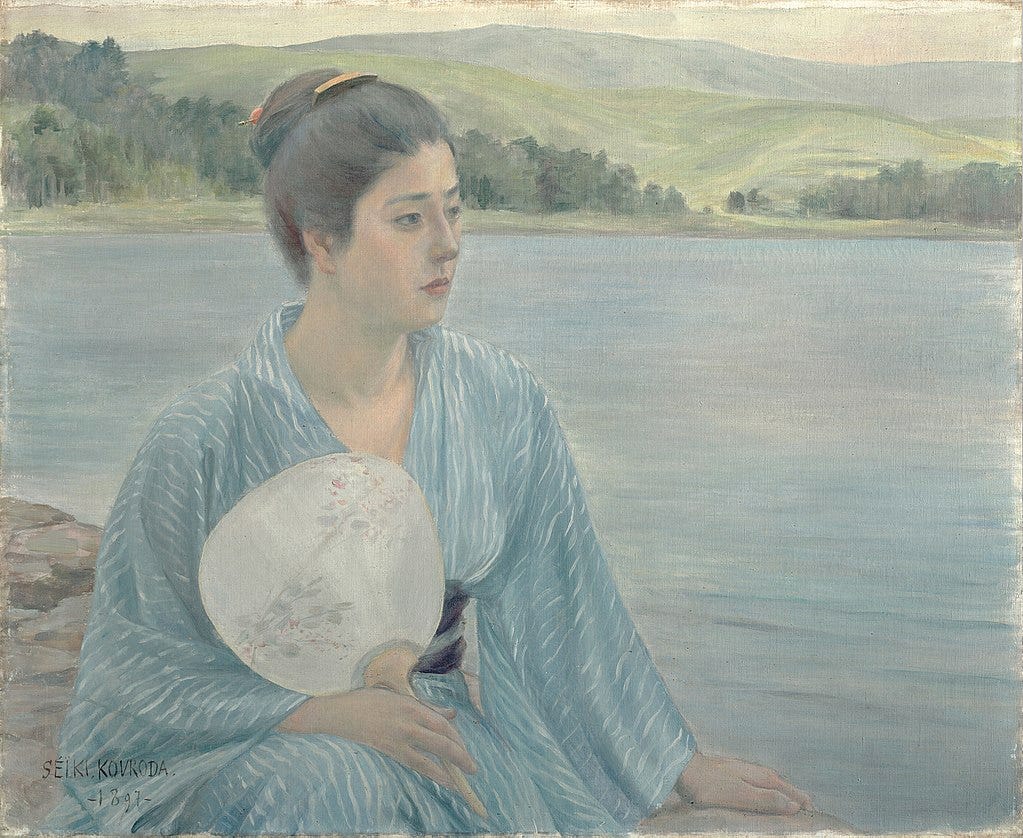

I guess most people who like Japanese art would be familiar with this very famous painting:

It’s been turned to every graphic use you can think of, but it’s not actually a painting. It’s a wood block print, a form of art popular in the 19th century - called Ukio-e - to make something like postcards. It’s popular street art, probably the most famous example of it.

日本画 - Nihonga

The first two characters are just “Japan” (“Ni Hon”) or Japanese, and the second is for “ga” - painting or pictures. So, Nihonga just means “Japan pictures.” But of course there’s more to it than that.

As an artistic movement in Japan it was a response to western influences that had entered the country in the Meiji period, the 19th century, when the nation was opened up to the world once again after its long seclusion.

In this period, western style art using oil paint, called Yōga (洋画) - that doesn’t really look very non-Japanese to western eyes, to be honest - had a sudden surge in Japan, and there was a reaction to return to traditional Japanese techniques and materials. 洋画 didn’t really catch on, and remains a relic of the period of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Nihonga, however, has become an enduring and living tradition that has developed its own contemporary voice. It’s is a type of watercolour, done on thin washi paper1 or stretched silk, using powdered mineral pigments.

The main difference between Japanese and Western watercolour is the binder - the sticky stuff used to hold the pigments on the surface. In the West it’s mainly Gum Arabic, and in Japan its collagen glue2. Many of the normal techniques of Western watercolour we’re familiar with are used, but with a distinctively Japanese flavour.

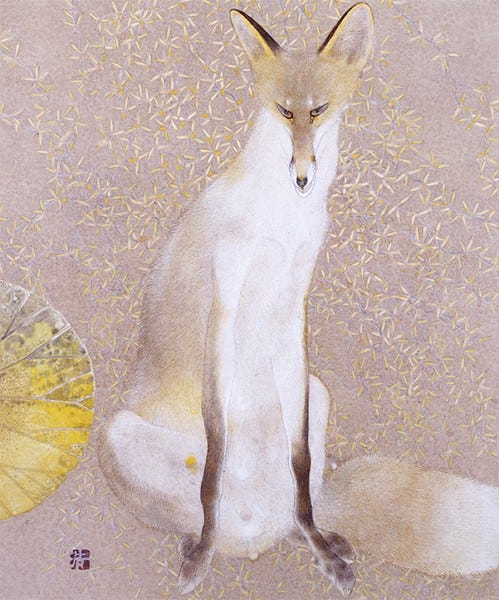

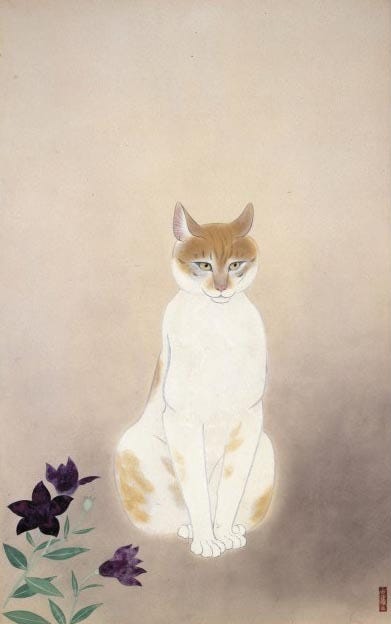

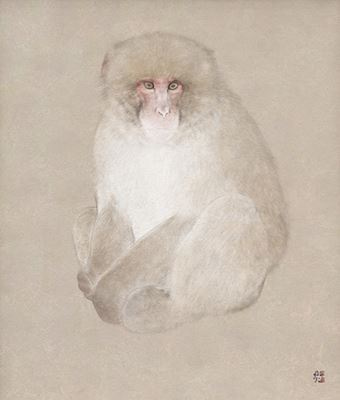

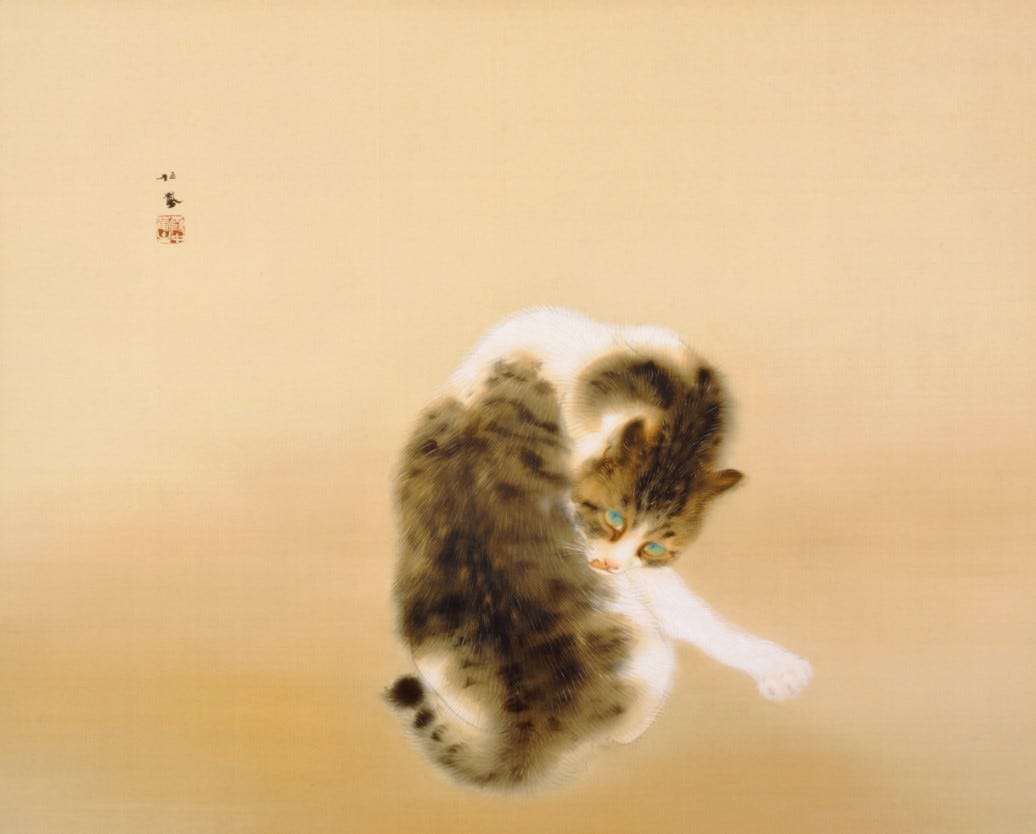

The emphasis is mainly on the natural world, animals, flowers, trees and forest scenes, falling autumn leaves and mountain landscapes, birds, fish and insects are the bulk of the movement’s subjects.

Typically, Nihonga relies on a close-to-nature palette with low value contrasts - low highlights and light shadows - and often muted colours.

Though this isn’t necessarily universal:

I hope you are enjoying the post. If you would like to support my work researching and recreating classical Christian sacred art in traditional techniques, subscribe to my Ko-Fi page, Hilary White; Sacred Art which is linked to my PayPal. It’s also where you can see my painting work and progress on projects.

Donations and sponsorships are crucial to my being able to continue this work; it keeps the lights on and self and kitties fed. You can also sign up to be a monthly patron. Right now I’m especially close to the wire, in truth, with rent covered but the winter gas bill - with its exciting new post-War-in-Ukraine charges - beyond my current reach. I appreciate the assistance more than you imagine. And many thanks again to those who have been helping.

Click to subscribe to World of Hilarity for more posts of this sort and feel free to drop a comment in the box. Let’s talk.

Because nihonga paintings are quite lightweight, done on paper stretched over a wooden frame, can be very large, with the scale allowing complex and detailed landscapes.

A balance between naturalism and abstraction

Contemporary nihonga painters have also embraced abstraction but without the overtone of bitter adolescent resentment and rejection of tradition so typical of western abstract painters. Nihonga abstracts retain their uniquely identifiable Japanese-ness, and even connection to natural forms.

One key ingredient in nihonga is the use of the particular pigment palette native to Japan. Some of the pigments are familiar - yellow ochre, cobalt blue and indigo are among my own most important colours - but, unlike in western “limited palette” painting, in Japanese painting colours are taken straight from the jar, without much mixing. (They can be bought online, but the shipping to Italy is prohibitive.) So a nihonga painter will use dozens of different pigments. To give a watercolour painting a particular Japanese feel, it is necessary to use Japanese colours.

One pigment in particular has stymied me in my efforts to find an equivalent.

This glowing, ghostly white is not what we would think of as a pigment at all, but is calcium carbonate - chalk - made by a special process from Japanese oyster shells. Called “gofun,” it has an extremely high light value and a pearlescent quality that ordinary mineral chalk can’t replicate.

Mineral chalk is what we use to make gesso, the undercoat that goes on a panel before painting. I’ve followed the instructions I found on a few videos but only have ordinary mineral chalk - gesso di Bologna - that comes out greyish, and no amount of Titanium white pigment seems to fix it.

It was so long ago that even I’ve half forgotten it, but it’s a little known Hilary-fact that I spent two years at the University of Victoria - my parents’ alma mater - following my mother’s footsteps and studying Japanese language and culture. It was an experimental course to see if adults could learn languages the way infants do, by constant exposure. We were completely terrified when she walked into the class on the first day and just started speaking Japanese to us. But it turned out she was right, and two years in I was astonished to find myself more or less conversational. I could at least give comprehensible directions to the tourists.

Needless to say I didn’t keep it up, and nearly all my Japanese is gone but some key polite phrases and words. I still retain a bit of grammar theory and I can order food in Japanese restaurants but I can’t get the gist of Japanese painting videos without the subtitles. But it was at least proof that you can learn things as an adult (if you can call 21 adult) that one would have thought very unlikely to be possible.

What I have retained from that time is a great respect for the Japanese visual sensibility, and their great love of the natural world, including its darker side, and often its humour.

What I love about nihonga painting is the perfect balance between naturalism and abstraction, delicate linearity and colour and volume, humour and respect for the subjects. There’s some insight into the grave dignity of the natural world on the one hand but an awareness of the ephemeralness of this life, and therefore a hint of the next, a kind of otherworldly atmosphere that reminds us that this life comes from a higher reality.

The too-long-didn’t-watch version is, it’s very strong paper that doesn’t disintegrate when used with water-based media. Made from the long fibres of a particular variety of Japanese mulberry tree. So unlike western watercolour paper it doesn’t buckle or lose its surface quality.

In Japan it’s called “nikawa” but is the same stuff I use all the time; rabbit skin glue is a crucial ingredient in Byzantine painting. It’s mixed with powdered chalk to create the gesso, the white primer that creates an ivory-hard, smooth and absorbent surface on the wood panel. Until I started watching Japanese painting videos I had never thought of using it as a pigment binder, but now I’m going to try it.