Christian Europe; down but not out

High time for an eye-candy post, don’t you think?

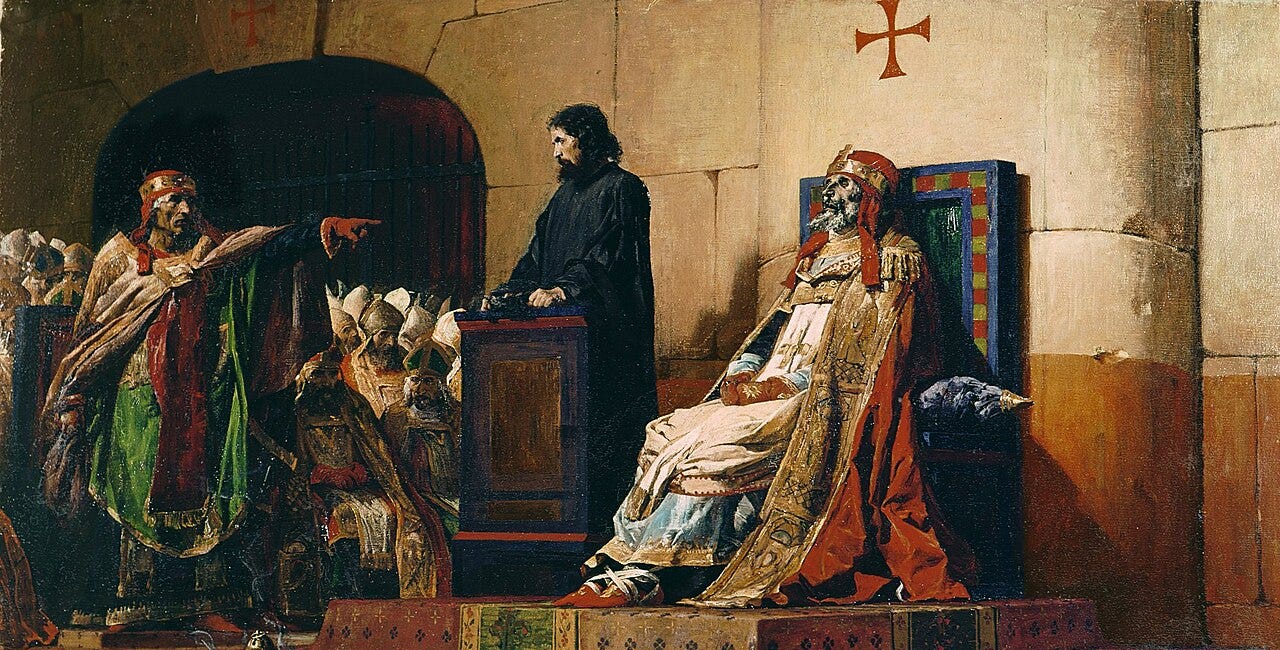

In our paid articles in the last couple of weeks we’ve been investigating the kind of “pre-medieval” period of Church history, that time between the fall of the old western Empire (Byzantium kept going) and what happened with the Carolingian revival fell apart. Let’s just say things were dark, in the Church and the world at large. The hierarchy reached a nadir of moral corruption and political obsession that makes our own time seem like a flowering of virtue. It’s called the “Saeculum obscurum” by historians because it almost seemed as if the light had gone out in the Church of Christ.

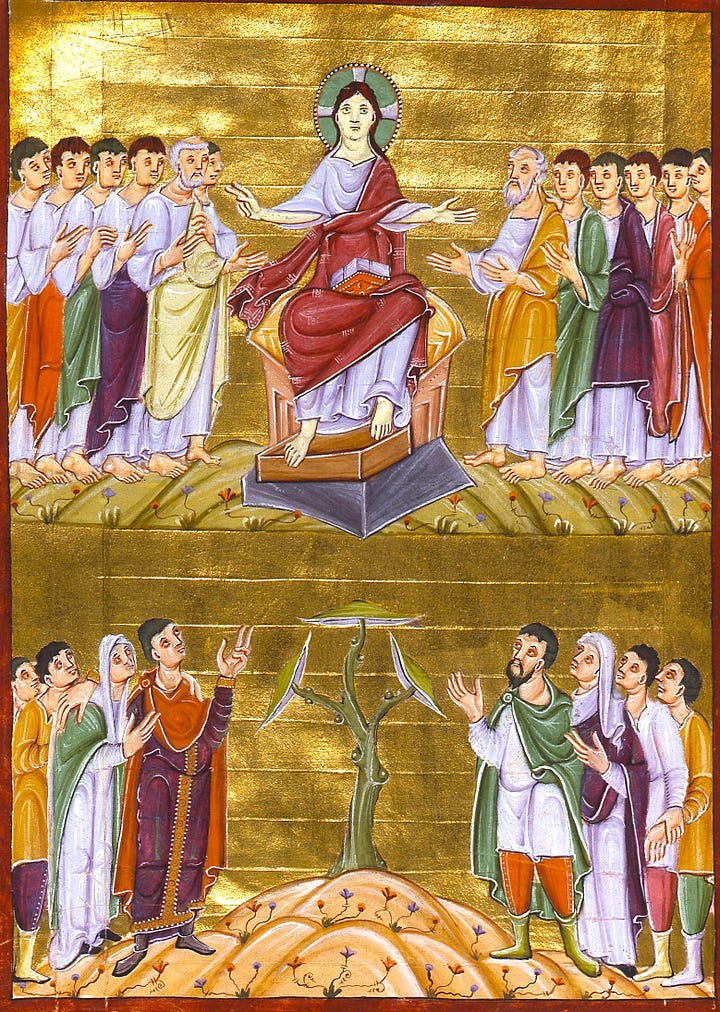

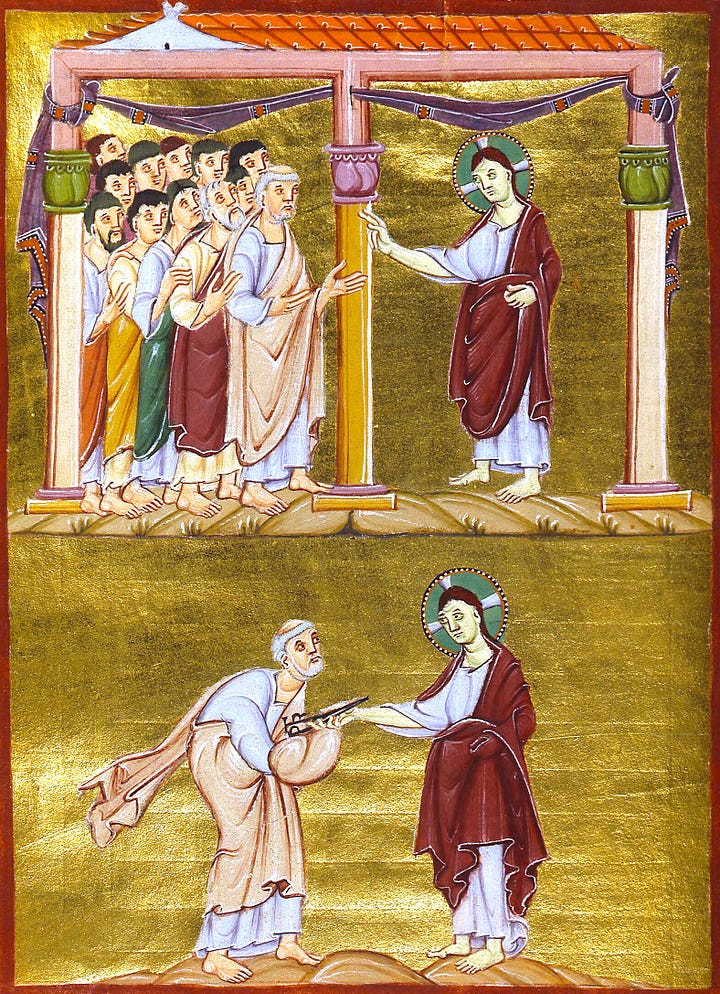

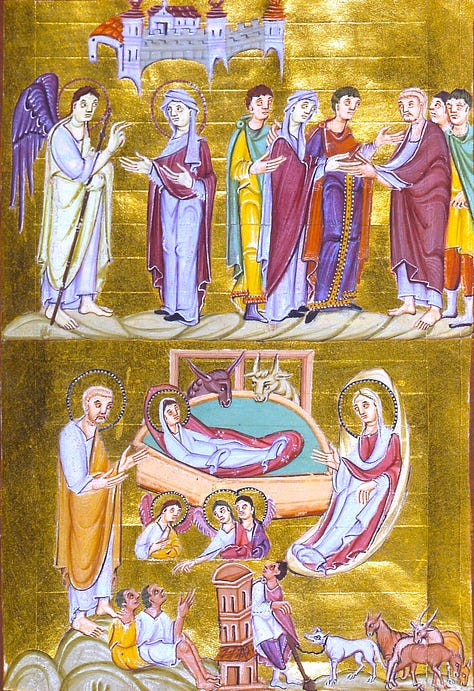

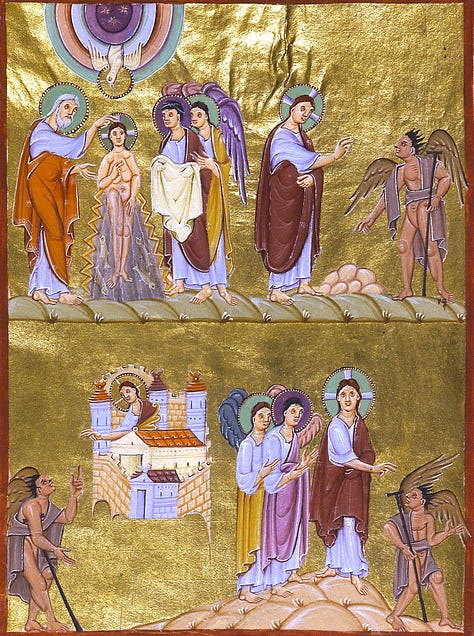

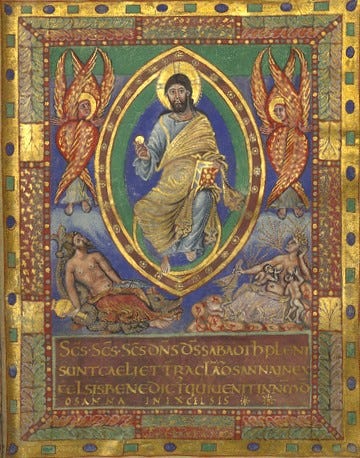

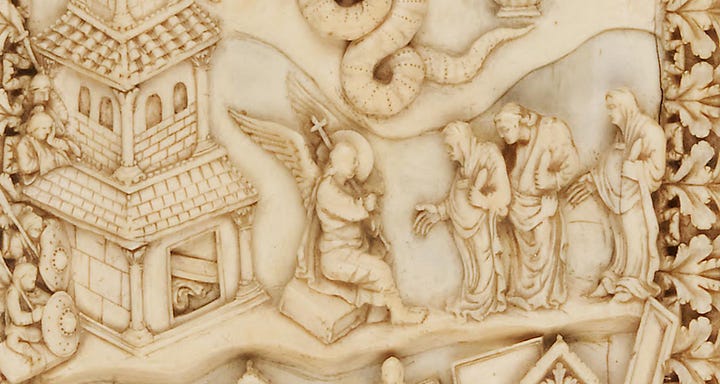

Today in this post for all subscribers, we’re going to have a look at some of the art of the Ottonian period. This was the time when the family of the Duke of Saxony decided to put everything back together. Otto the Great revived the old Carolingian dream, formed the Holy Roman Empire, subdued the rival dukes and petty kings, beat back the savage heathen barbarians, and brought the wayward and grotesquely corrupt popes back to their duties.

Ottonian art, as we shall see, was a bling-encrusted triumphal shout of joy and exuberance; “We’re not done yet!”

Subscribe to read all about it in the first in the series, here:

At the Sacred Images Project we talk about Christian life, thought, history and culture through the lens of the first 1200 years of sacred art. The publication is how I make my living, supported by subscriptions, so apart from plugging my shop, there is no advertising or pop-ups. It’s my full time job, but it’s still not bringing a full time income, so I can’t yet provide all the things I want to and am planning for.

You can subscribe for free to get one and a half posts a week.

For $9/month you also get the second half of the third post, plus a weekly paywalled in-depth article on our great sacred patrimony. There are also occasional extras like downloadable exclusive high resolution printable images, ebooks, mini-courses, videos and eventually podcasts.

If you would prefer to set up a recurring donation in an amount of your choice, or make a one-off contribution, you can do that at my studio blog.

This helps me a lot because the patronages through the studio blog are not subject to the 10% Substack fee.

People tell me all the time - and I’ve found this myself - how difficult it can be to find really nice religious cards and decorations for Christmas.

There are still plenty of nice things to browse:

The story thus far - falls of empires, the cosmic struggle between chaos and order…

For a long time, I’d really only paid attention to the glories of the various art forms that I loved, and not much to how political, religious and cultural changes had brought them into existence. But if we want to really understand something, we have to look at its context.

So, I’ve been wanting for ages to do a deep dive into the tumultuous period that anti-Catholic Whig historians of the 19th century used to dismiss as an irrelevant “dark ages”. And I’ve found that in some sense, the label was in some sense deserved, though not in the sense they meant. It was definitely not a time when nothing much happened.

In fact, it was a time of a titanic cosmic struggle, for about 400 years after Rome died, between the forces of chaos and of order. And there were definitely dark moments. But in truth, this struggle wasn’t at its core political or military; it was spiritual, cultural, and existential, played out on a grand stage where entire societies teetered between collapse and renewal.

Chaos came in many forms: the disintegration of centralised authority - several times - waves of invasions by brutal, heathen barbarians, and the moral decay of crucial institutions like the Church itself. Yet, the forces of order, though often overwhelmed, never entirely vanished, preserving and rebuilding through small acts of resilience - monks copying manuscripts, kings imposing laws, and reformers dreaming of something greater.

It was from this crucible of conflict that the seeds of Christendom as we know it were planted, growing slowly but inexorably into the towering civilisation that would define the European medieval world.

And really, it’s damned exciting!

So, if you’re not a paid member and you were wondering what we’ve been talking about the last couple of posts, it’s that: the struggle between collapse and renewal, chaos and violence and anti-civilisational darkness - the results of the Fall of Man writ large on the vast stage of western Europe - and the equally human desire to create stability, prosperity, happiness for everyone, the rule of law and security.

I had a feeling that a lot of people in our time, given our apparent race into a similar age of collapse and chaos right now, might recognise some of this, and perhaps be encouraged by it. (It has a happy ending, right?)

Otto and his empire’s art

This week we introduced the Ottonian period, the revival and development, by a single family of Saxon kings, of Charlemagne’s grand idea of a reboot of the long-lost western Roman empire, but this time under the sweet yoke of Christ in His holy Church. This is the real start of what was to become known for all time as the Holy Roman Empire.

Read all about the guy who pulled it out of the fire, here:

And we’ve talked about Carolingian, and a little about Ottonian, art here, here, here and here.

Things hadn’t gone so well for Charlemagne’s grand scheme since the emperor’s death in 814. Despite his ambitious reforms and plans for cultural and religious revival, the Carolingian Empire barely outlasted Charles the Great himself. By the mid-9th century, the empire was already fracturing under the strain of internal divisions and external pressures. The Treaty of Verdun in 843, which divided the empire among Charlemagne’s grandsons, marked the beginning of its decline, as the unified Christian realm he had envisioned splintered into competing kingdoms.

Into this boiling cauldron of native political instability, dove relentless invasions from pagan foreigners, Vikings in the north and west, Magyars coming across the mountains in the east, and Saracens making incursions up from the Mediterranean. Meanwhile, the Church, which Charlemagne had sought to reform and strengthen, fell prey to the same forces of decay, with bishops and abbots - seeking power and wealth - aligning themselves with local feudal lords in the north and grossly corrupt Roman aristocratic families in Italy.

By 912, when Otto, son of Henry the Falconer, was born into the ruling ducal family of the Duchy of Saxony, all that remained of Charlemagne’s legacy was a shadow of his empire, a patchwork of feuding states and a Church in dire need of moral renewal - and a memory of his dream.

The world Otto inherited was one of both peril and possibility. The Saxon duchy, though strong and relatively stable under his father Henry’s rule - despite occasional rebellions by fractious family members - stood on the edge of a fractured and teetering Europe. Political authority was decentralised, with dukes and local lords - with their private armies - wielding more power than the nominal kings of East Francia (Germany).

The Church, which had once been Charlemagne’s ally in unifying the empire, was boiling with corruption, its spiritual mission compromised by rampant simony, nepotism, and the entanglements of feudal politics. Yet amidst this turmoil, the seeds of reform and renewal were beginning to take root - seeds that Otto himself would one day nurture into the foundations of a revived Christian empire.

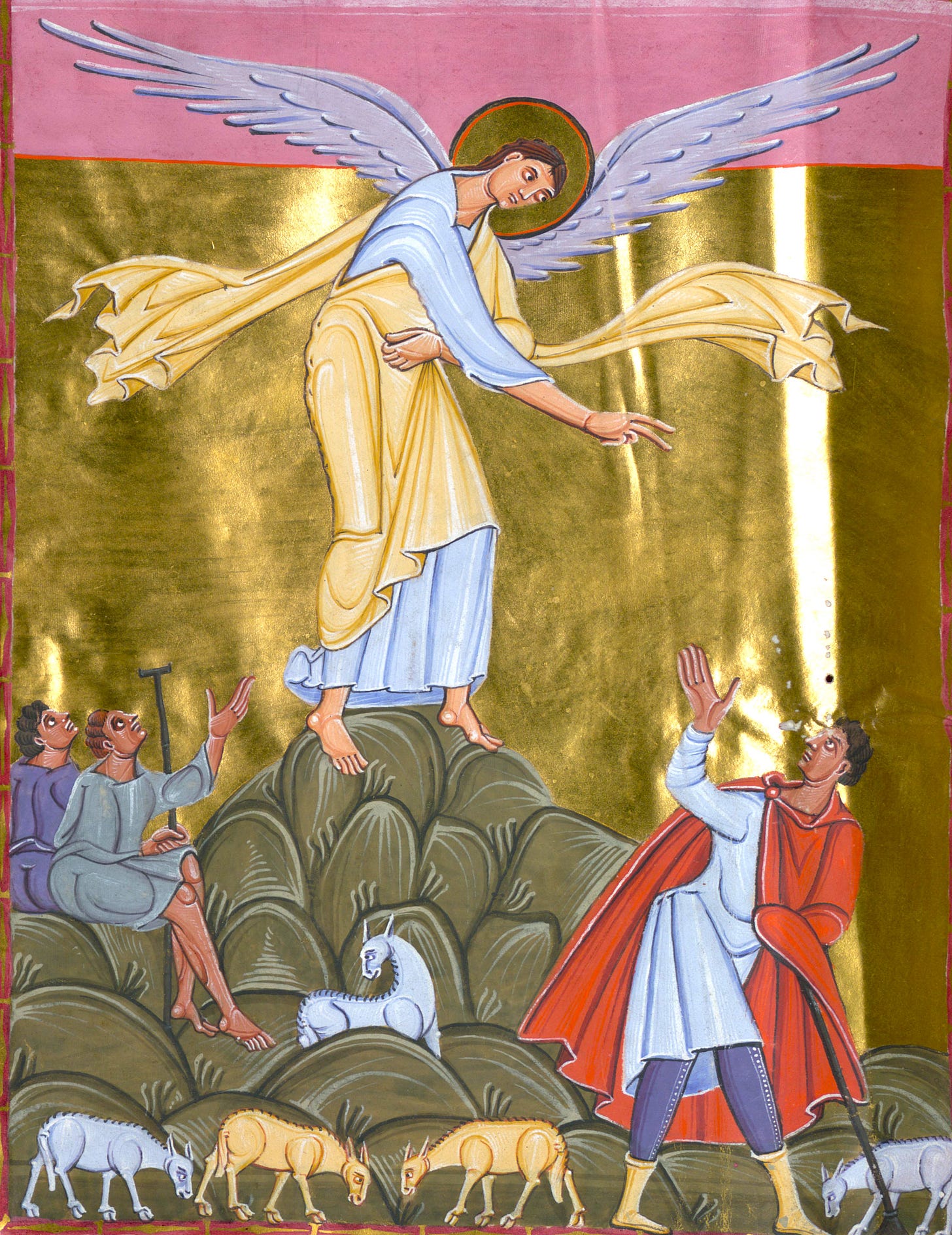

Ottonian art - a Carolingian/Byzantine/Roman do-over

Ottonian art is deeply connected to, and develops organically from the ancient Christian Byzantine traditions, reflecting the close political and cultural ties between the Ottonian Empire and the Byzantine court. Byzantine influence is evident in gold-ground backgrounds, a tradition that would survive in western sacred art all the way through to the end of the Gothic. Manuscript paintings (and presumably the now-lost wall frescos) showed the same hieratic poses and frontal figures that have been used in Byzantine art to depict the majesty of God since its earliest days in Egypt and Greece.

It retained the Carolingian fascination with classical antiquity but displayed a marked shift, westward and north, in its execution and purpose. While Carolingian art often emphasised naturalistic, very classical, figures and a revival of Roman artistic ideals, Ottonian art leaned towards greater abstraction and symbolism. Figures in Ottonian illuminated manuscripts, sculptures, and metalwork often exhibit elongated proportions, stylised gestures, and a sense of spiritual gravity rather than physical realism. It was the true beginning of medieval European sacred art’s love of stylisation and its adaptation of the Byzantine concept of canonical symbolic figures, away from visual realism.

Illuminated manuscripts of the Ottonian period, such as the Gospel Book of Otto III, are characterised by:

Vivid colour palettes: rich purples, greens and blues, with a LOT of gold paint and leaf, emphasising the divine origin of the empire’s mandate to govern.

Symbolic iconography: Figures and scenes are less about narrative realism and more about conveying theological truths.

Hieratic compositions: Emphasis is placed on the centrality of Christ or the ruler, often in a heavenly context.

Ottonian art was deeply tied to the ambitions of the Ottonian emperors to legitimise their rule and connect themselves to both the legacy of the Carolingians and the ancient Roman Empire. Geographically, Ottonian art flourished primarily in the German-speaking regions of Europe, especially around important imperial and ecclesiastical centres like Aachen, Cologne, and Hildesheim.

The latter, under the patronage of Bishop Bernward, became a particularly important hub for Ottonian innovation, producing masterpieces such as the bronze doors of Hildesheim Cathedral, which narrate biblical stories with dramatic expression and typical Ottonian symbolic, linear clarity.

Technological Advances in Painting: The Ottonian Manuscripts

The brilliance of Ottonian manuscripts was not just a testament to artistic skill but also to the technological developments of the period, particularly in the use and preparation of pigments. While lapis lazuli—associated with the vivid ultramarine blues of later medieval art—was rarely used due to its scarcity and expense, Ottonian illuminators relied on locally sourced and innovative alternatives to create their striking colour palettes.

Blues from Azurite:

You might have noticed that the palette of the manuscript paintings isn’t quite what we’re used to seeing, particularly the blues. Blue is a notoriously tricky colour to get, and the one we’re used to seeing in most medieval art was even harder to get before the empire had settled things down and started developing some European prosperity and, crucially, trade routes east. The pigment, called Ultramarine (“across the sea”) comes from a mineral called Lapis lazuli that came to Europe along a torturous route from Afghanistan. By the 12th century, it had became more prominent as trade routes between Europe and Central Asia expanded, particularly with the flourishing of Venetian and Genoese trade networks but in the Ottonian early days, it was extremely rare and more precious than gold.

Azurite, a copper-based mineral, was the primary source of blue in Ottonian manuscripts. This pigment, mined in regions of Germany, Hungary, and France, produced a vibrant, slightly greenish-blue tone. Its availability made it a practical choice for illuminators striving to achieve richly coloured decorations while remaining cost-effective.

Extensive Use of Gold:

Gold leaf and powdered gold played a central role in Ottonian illumination, underscoring the manuscripts’ spiritual and material value. Applied as backgrounds, borders, and highlights, gold added a divine radiance that reflected theological themes and symbolised the “uncreated light,” eternal imperishability and infinity of the heavenly realm. The refinement of techniques for applying gold leaf - including turning it into gold ink or paint - allowed illuminators to achieve intricate designs with unparalleled brilliance.

A Vibrant Palette:

The Ottonian palette included vivid reds from cinnabar (vermillion) and red lead (“minium” from which the term “miniature” comes), bright greens from verdigris, and warm yellows from orpiment. These pigments, many of them extremely toxic1, were combined and layered with exceptional skill, creating depth, contrast, and luminosity that distinguished Ottonian manuscripts from their Carolingian predecessors.

Orpiment was known at least as far back as ancient Egypt, and there are Egyptian manuals that warn art students about the pigment’s extreme toxicity. It’s known as one of the world’s most dangerous pigments, and is banned in the EU, along with lead white, making it a favourite contraband item passed between painters in Europe on the sly. No joke.

I'm always amazed at what has survived the ravages of time, war, revolution, reformation, infestation, and weather. I just wish more of these items were being used as originally intended, though. I understand why they are locked away now, given their antiquity and rarity, but museums (no matter how well done) cannot convey the purpose or context of things. Last summer, for instance, I saw a ceramic 4th century Syrian prosphora seal ("prosphora" is Orthodox communion bread - ours is a leavened bread, and it is stamped with a seal before baking) in a museum in Toronto. As one of my church's prosphora bakers, I wished I could have rescued that seal and put it to use - it would have made for a tangible connection with 2000 years of fellow Christians (especially as many in my parish are Syrian). I think much the same with these manuscripts - it would be good if they could somehow be given an occasional liturgical use, and that way connect us all with our brethren of past centuries.

I'm not surprised about painters still using Lead White or other pigments on the sly. I've never understood the EU's near total unconditional ban on lead - handled properly (as people have been doing for millennia now), lead is darn useful (this is a sore spot for me given my day job).

Wow, you are right about all that gold - it dazzles. Seems like no expense was too great to create these staggering pieces and Ms pages. Amazing, thank you for introducing beautiful things I never was aware of