Spooky Goodie Bag for Oct 18: Sienese art and the Black Death

Below the fold: more photos & videos from our trip this summer to Siena

We’re back to Siena, but in a time of death and disaster

Star of Heaven,

who nourished the Lord

and rooted up the plague of death

which our first parents planted;

may that star now deign

to hold in check the constellations

whose strife grants the people

the ulcers of a terrible death.

O glorious star of the sea,

save us from the plague.

Stella caeli extirpavit, a prayer in time of plague, 15th century

It might not catch your attention the first time you see it. Pietro and Ambrogio Lorenzetti - brothers who were major figures in the Trecento Sienese painting scene along with their better-known compatriots Duccio and Simone Martini - both died the same year: 1348.

By this fateful year, Siena was a flourishing city-state, rivalling Florence in wealth, artistic output, and political influence. But the arrival of the Plague led to a dramatic and irreversible decline that shaped the city’s future for centuries.

The Black Death’s devastating sweep across Europe, from 1347 to 1351, left a haunting mark not only on the population but also on the artistic psyche of the era. It is estimated to have killed between 30% and 60% of the European population. This amounts to approximately 25 to 50 million people out of a population of about 75 million.

Siena’s population was hit particularly hard by the Black Death, with an estimated 60% of its inhabitants perishing in a short span. Entire neighbourhoods were wiped out, and the sudden, widespread loss of life plunged the city into chaos. Public health and burial systems were overwhelmed, and many of the city’s prominent citizens, including government officials, clergy, and patrons of the arts, succumbed to the disease.

Siena’s duomo seems a bit small, if you’re used to Florence or Rome. There’s a good reason. Our friend Chris explains that what was originally planned was twice the size, but something happened, and it was never finished.

With so many dead, labour shortages became a serious problem across Europe, disrupting trade, agriculture, and other industries, including the trades supporting art. Wealthy families and patrons who had supported the arts and architecture disappeared, leaving fewer resources and less interest in large-scale artistic projects. The plague essentially crippled Siena’s ability to continue its growth and rival its neighbours.

Some spooky English folk music to go with the post.

The catastrophic death toll caused a profound social, economic, and cultural upheaval, leaving Europe scarred for generations.

In the midst of this upheaval and devastation, the artistic flowering of much of the Italian late Gothic died, as cities like Siena, once vibrant centres of creativity, were gutted by the loss of both their populations and their finest artists. The deaths of painters such as Ambrogio and Pietro Lorenzetti1 marked the end of an era. With entire workshops and supporting industries decimated and patrons struggling to rebuild, the aesthetic innovations of the late Gothic period were abruptly halted.

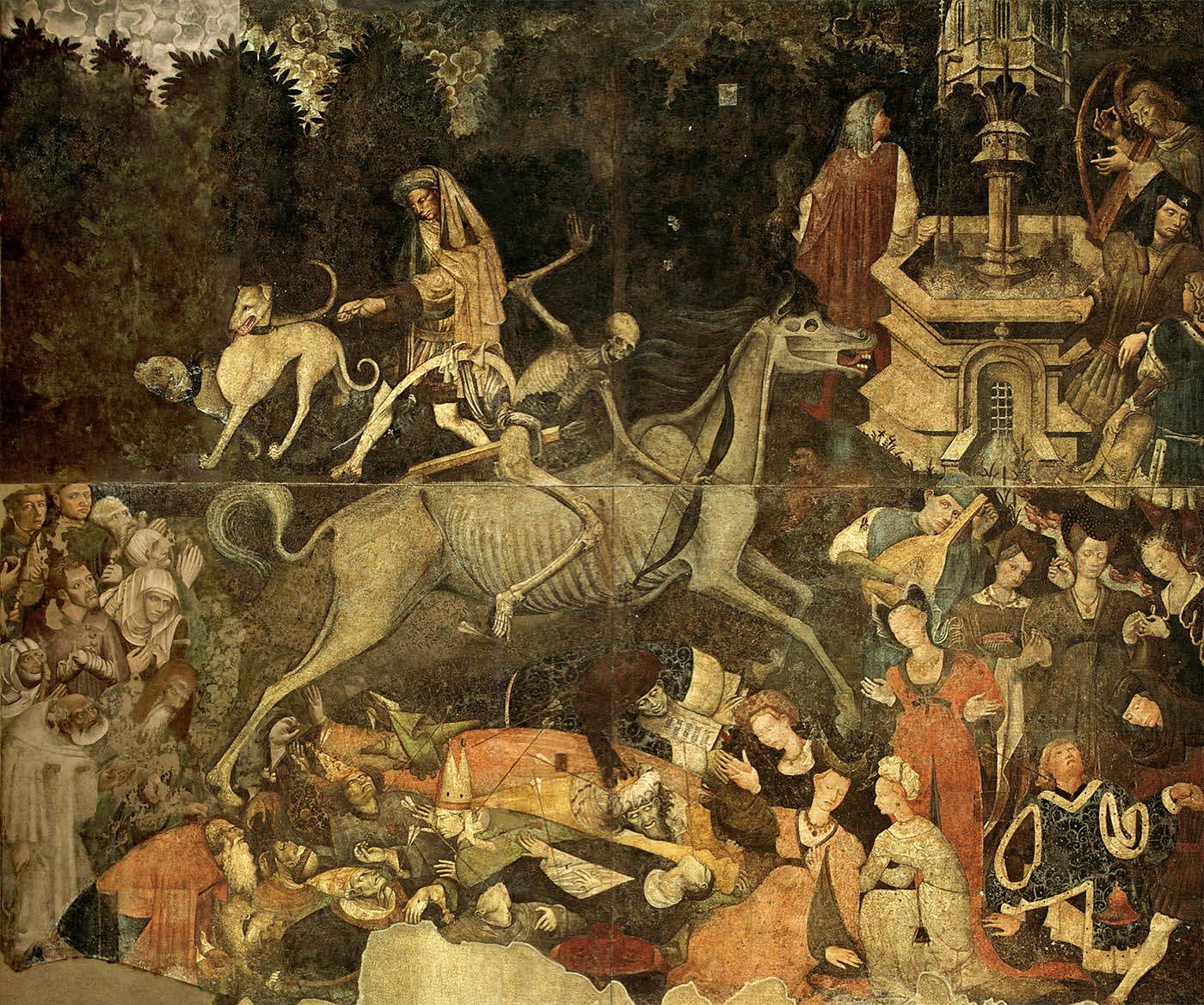

What followed was a shift toward a more sombre, introspective style, as surviving artists grappled with the trauma of the plague and the realization of life’s fragility. The delicate and serene beauty of the Sienese school, with its deep, luminous colours and elegantly draped and elongated figures, gave way to a more restrained and sometimes morbid realism that mirrored the collective sorrow of a civilization in mourning.

Common Themes in Post-Plague Sienese Art:

Somber Tones and Introspective Figures: Figures in post-plague Sienese art often have more serious, pensive expressions, reflecting the pervasive awareness of death.

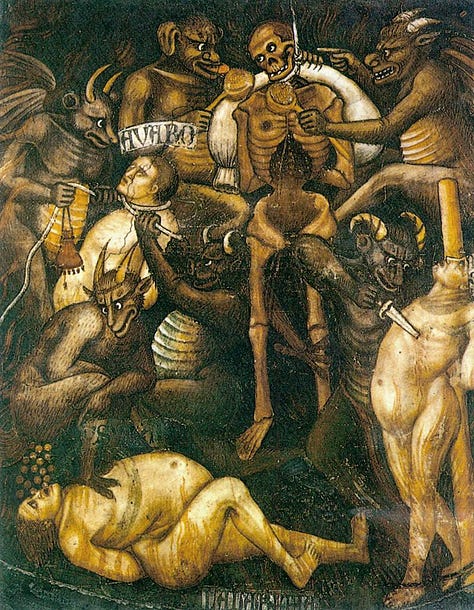

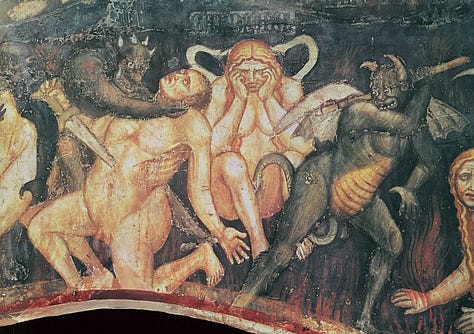

Focus on Salvation and Judgment: Themes of the Last Judgment, divine intercession, and the fragility of life became more prominent.

Heightened Religious Fervor: Saints, especially those associated with healing and plague protection, such as St. Sebastian and St. Roch, became frequent subjects.

Emphasis on Mortality: Death, decay, and suffering were recurring motifs, as seen in frescoes and altarpieces, where artists depicted the grim realities of life and the urgency of salvation.

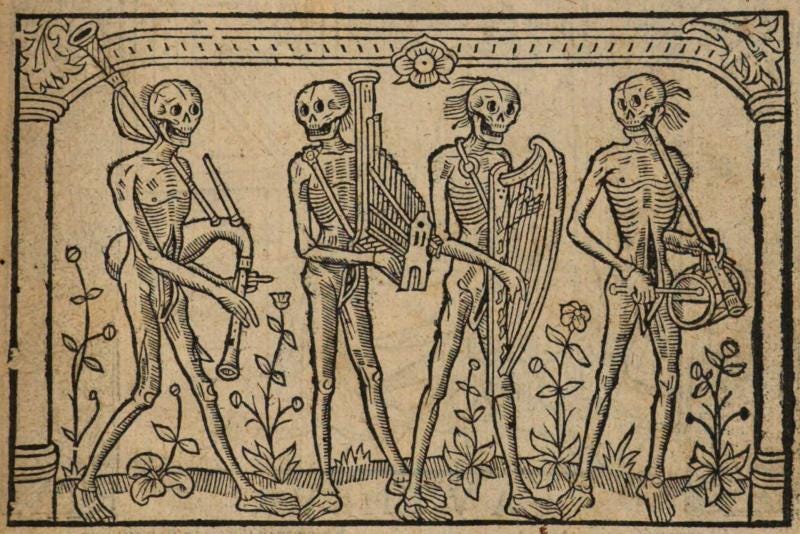

Memento Mori: Remember, O Man…

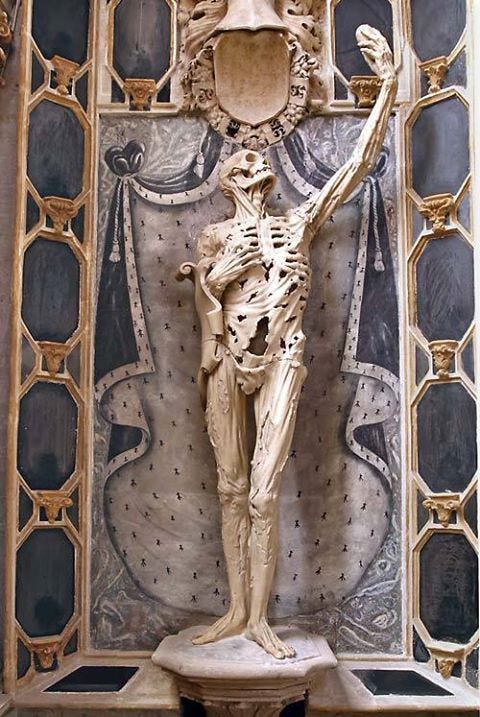

The memento mori, Latin for “remember you must die,” emerged as a prominent theme in medieval European art, particularly after the Black Death. Skulls, hourglasses, extinguished candles, and wilting flowers became key symbols in memento mori art. In funerary art, transi tombs, depicting decaying corpses instead of serene effigies, were unflinching portrayals of bodily corruption, the inevitability of death and pointlessness of worldly vanity and self-seeking.

These stark visual reminders of mortality became an ever-present theme in art that never entirely died out in the west. The trauma of seeing entire communities decimated in the space of weeks and months, and the collective grief that followed, fostered a late medieval culture deeply preoccupied with death.

These works may seem macabre today, but taken in the context of the Christian hope of eternal heavenly glory, they served an important spiritual function, reminding viewers that death was not the end but a gateway to either eternal bliss or damnation. Memento mori art pushed believers to reflect on the state of their souls, while there was still time to do something about it.

Virgin of the Painted Foliage prints

Right… that seems a bit grim.

Let’s look at something beautiful…

I’ve really enjoyed our discussion this week about the gorgeous late Gothic, or Early Netherlandish painting, the “Virgin and Child in a Landscape,” by the unknown “Master of the Embroidered Foliage”. So much so that I thought the time had come to start putting this year’s Christmas things in the shop, and that she should take pride of place.

Order here: Wood panel print

I’m happy to offer this print on a wood panel. The original was painted in the new technique of oils on a wood panel, so this high quality art print will give a good approximation of what the original might have looked like. It would make a lovely gift, and a gorgeous addition to any home prayer or icon corner, or home chapel, or just on a wall.

I’m offering two sizes that are very close to the proportions of the original painting, 10” x 15” and 13” x 19”.

If you would like it printed on canvas, museum quality archival paper or some other type of support, please drop me a note in the DMs and we can work out how to get you want you're looking for. The printer offers matting and framing as well (bur probably not the kind with the curlicues and gold leaf I think she deserves).

For the moment this can only be printed and shipped within the US. But I think I kind of want one myself, so I’m going to be looking around for a European printer who can ship on the continent and to the UK. I’ll keep you updated.

You can find more prints, including some of my own work, here:

The Sacred Images Project is a reader-supported publication where we talk about Christian life, thought, history and culture through the lens of the first 1200 years of sacred art. It’s my full time job, but it’s still not bringing a full time income, so I can’t yet provide all the things I want to and am planning for. You can subscribe for free to get one and a half posts a week.

For $9/month you also get the second half of the weekly Friday Goodie Bag post, plus a weekly paywalled in-depth article on this great sacred patrimony. There are also occasional extras like downloadable exclusive high resolution printable images, ebooks, mini-courses, videos and eventually podcasts.

If you would prefer to set up a recurring donation in an amount of your choice, or make a one-off contribution, you can do that at my studio blog.

This helps me a lot because the patronages through the studio blog are not subject to the 10% Substack fee.

In the paid section “below the fold” of today’s post we’ll revisit Siena. I’ve still got a passel of photos and video clips from our trip this past summer. We weren’t able to get to the national gallery of Siena or the Ducal Palace. Got to save something for a second trip, right?

We arrived pretty promptly in the morning, found a place to park near the Dominican church, about 8:30. It was already over 80F. We strolled around the Head Church - where I got a surreptitious illegal photo of St. Catherine of Siena’s head - but wanted to move on. On the way over to the Duomo, we stopped in St. Catherine’s family home. Then we found our way to the lower part of the Duomo where there was a nice coffee bar to have a rest and a sandwich, before we took a look at the magnificently frescoed Baptistry.

From there we climbed the stairs to the next level and visited the recently re-discovered and restored ancient crypt church with its lost cycle of frescos.

We have looked very closely at the great Maesta by Duccio, which was the main reason I wanted to go to Siena (and want rather desperately to go back as soon as possible).

Today I think we should take a stroll together around the rest of the diocesan museum. Just a whole bunch of Sienese eye-candy.

Subscribe to join us below the fold: