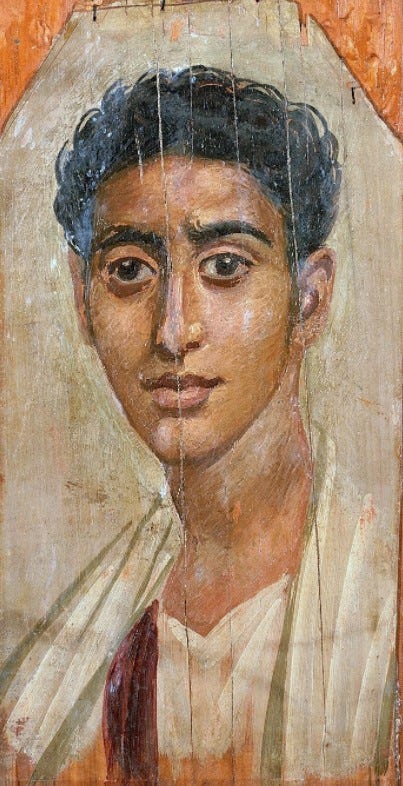

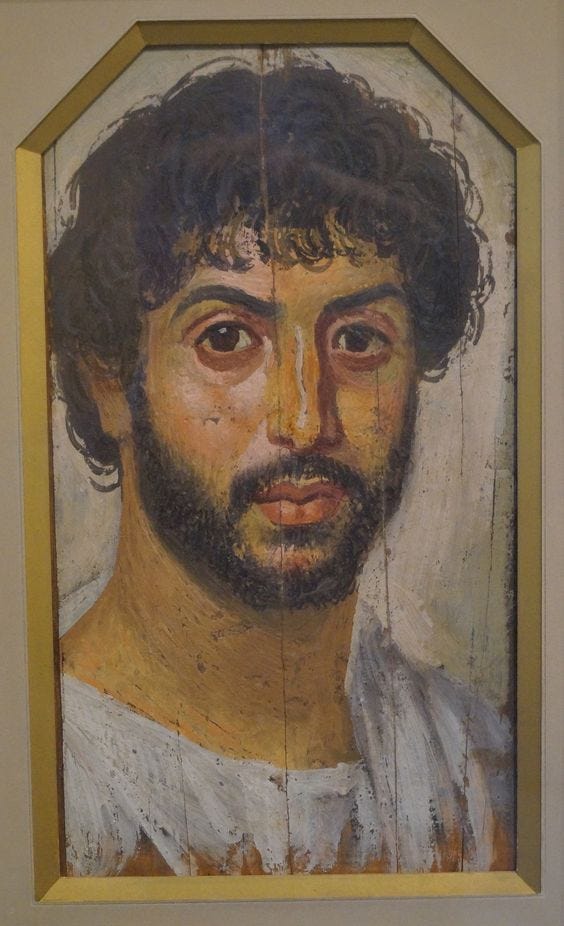

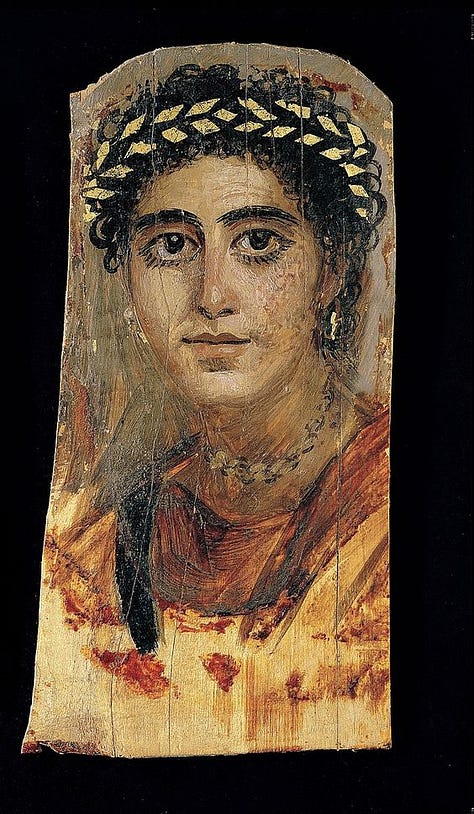

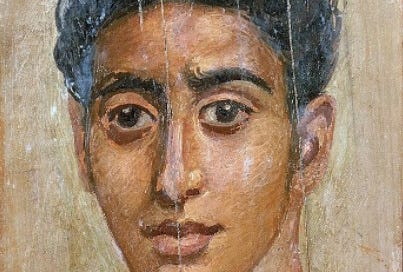

Who was this charmingly attractive young man, with the open, welcoming expression in the peak bloom of life? It’s a painting on a wood panel discovered on his mummy case. A fashion of the 1st century Roman Egyptians was to create these lifelike portraits, often of very young subjects, to place over their faces in death.

We’re going to talk today about some extraordinary discoveries from ancient Egypt and Roman Egypt (1st-7th century) that had a great influence on later Christian styles of painting, especially Byzantine iconography.

I will pause to thank the many - 50 as of today - who subscribed as new readers since I posted my plea, … “A note to our many new free subscribers”… 19 of whom signed up as paid members. Welcome everyone, and thank you. It’s certainly very encouraging to know that so many find these topics fascinating and are willing to put down hard earned money to know more. Please feel welcome to leave comments below.

We are significantly further ahead in the effort to raise the percentage of paid to free subscribers than we were a week ago, from barely 2% to just under 3%, but this is still well below the standard on Substack for a healthy, sustainable 5-10%.

If you would like to accompany us into a deep dive into these spiritually and culturally enriching issues, to grow in familiarity with the inestimably precious treasures of our shared Christian patrimony, I hope you’ll consider helping me meet that goal by taking out a paid membership, so I can continue doing the work and expanding it.

You can also make a one-time donation or set up a monthly patronage at my studio blog…

When you set up a monthly patronage for $9/month or more (you get to pick the amount) you automatically get a free full-membership here (seems only fair).

You can also browse around the shop where my own work is made available as prints and other items.

This week’s featured work is my graphite drawing of the Crucifixion in the style of the 13th century Umbrian panel crucifixes.

To order a high quality art print, click here : "Christus Patiens," a crucifixion in the 13th c. Umbrian style

~

And now, back to our show!

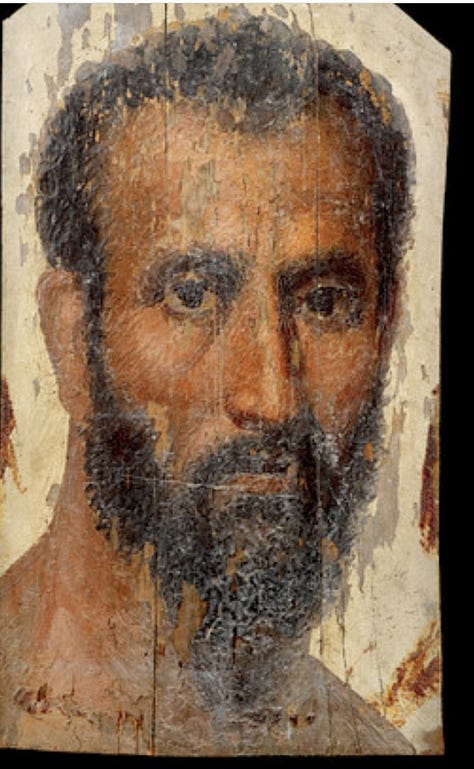

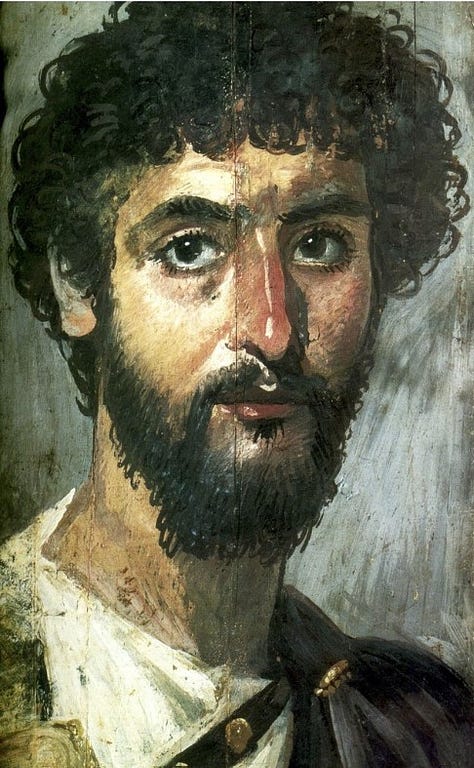

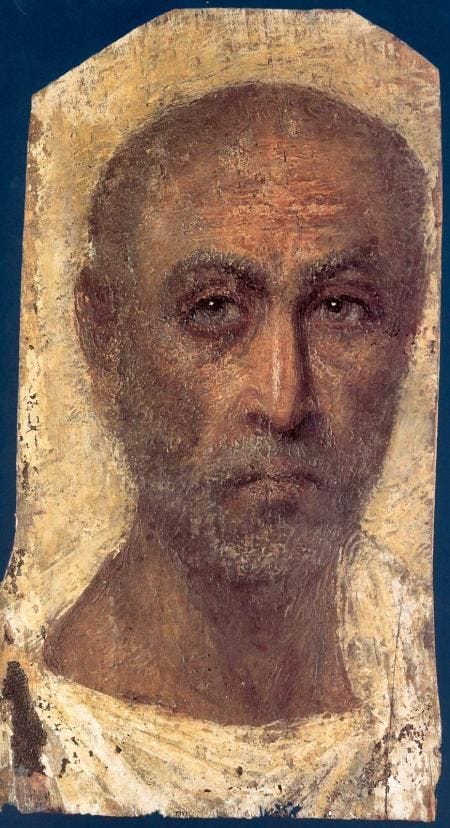

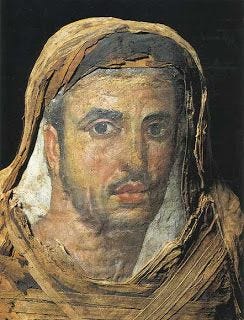

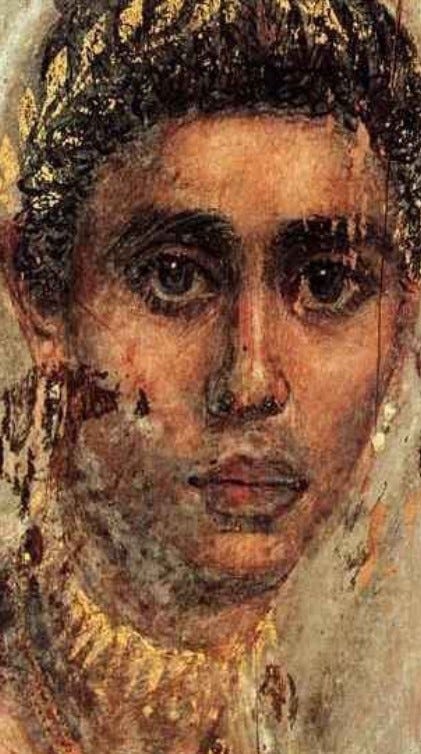

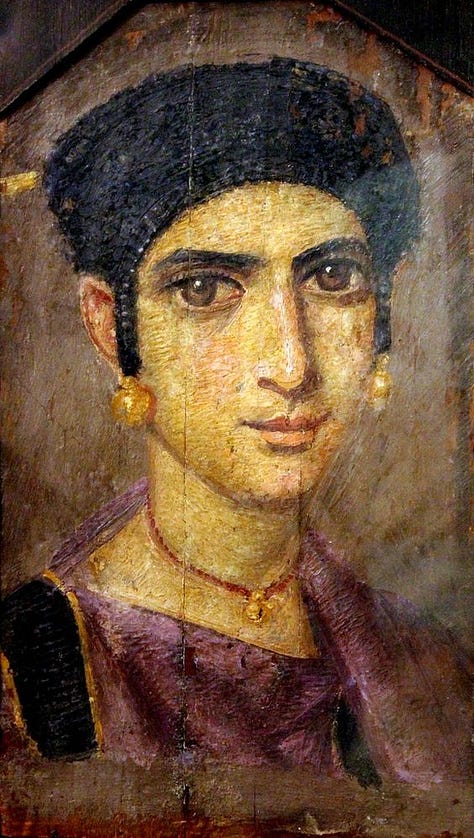

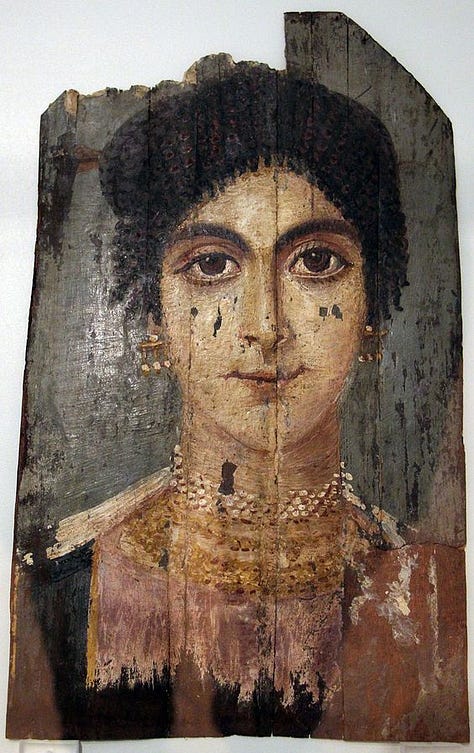

These naturalistic portraits - some verging on “photorealistic” - painted on wooden panels, adorned the faces of mummies from the 1st century BC to the 3rd century AD.

Unlike the traditional, stylized depictions of traditional classical Egyptian art, Fayoum portraits captured individuals with remarkable realism.

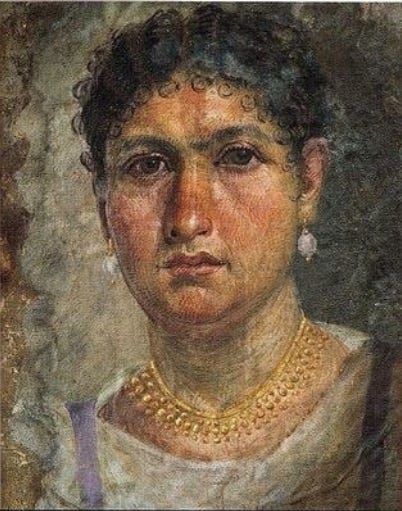

We see young women adorned with jewellery, their portraits glittering with real gold leaf, serious men of affairs with thoughtful expressions, and even children.

Many of the images are so lifelike that we feel we would like to know and speak to them; their smiles make us want to smile back.

These remarkable finds were unearthed primarily in the Faiyum Basin in the 19th century, an area southwest of modern-day Cairo. Many of the portraits came to light during this period. Italian explorer Pietro della Valle is credited with seeing the first ones in the early 1600s, but large-scale excavations by Flinders Petrie in the late 1800s uncovered many more.

The Fayum portraits hold immense artistic significance, bridging the gap between formalised Egyptian and naturalistic Greco-Roman styles, using the encaustic technique in which pigments are mixed with hot wax. Most importantly, these portraits offer a window into the lives and appearances of ordinary people in Roman Egypt, a stark contrast to the focus on symbolic depictions of divine myths, with their tangle of religious, mythological and philosophical meanings, in traditional Egyptian art.

A few Fayum bullet points:

The portraits show a unique blend of Egyptian and Roman influences. Emerging during the period of Roman rule of Egypt1, they combine the Egyptian tradition of mummification with the Greco-Roman artistic style of realistic portraiture.

Hellenistic Influence: The Hellenistic period (323-31 BC) following Alexander the Great's conquest introduced a stronger emphasis on realism in Egyptian art. This is particularly evident in sculptures, where figures were depicted with more lifelike proportions and expressions.

They show a range of social classes: While they were certainly a funerary practice of the elite, the cost of a Fayoum portrait was not out of reach for many middle-class Egyptians. So, unusually for ancient art, they depict a broad range of social classes.

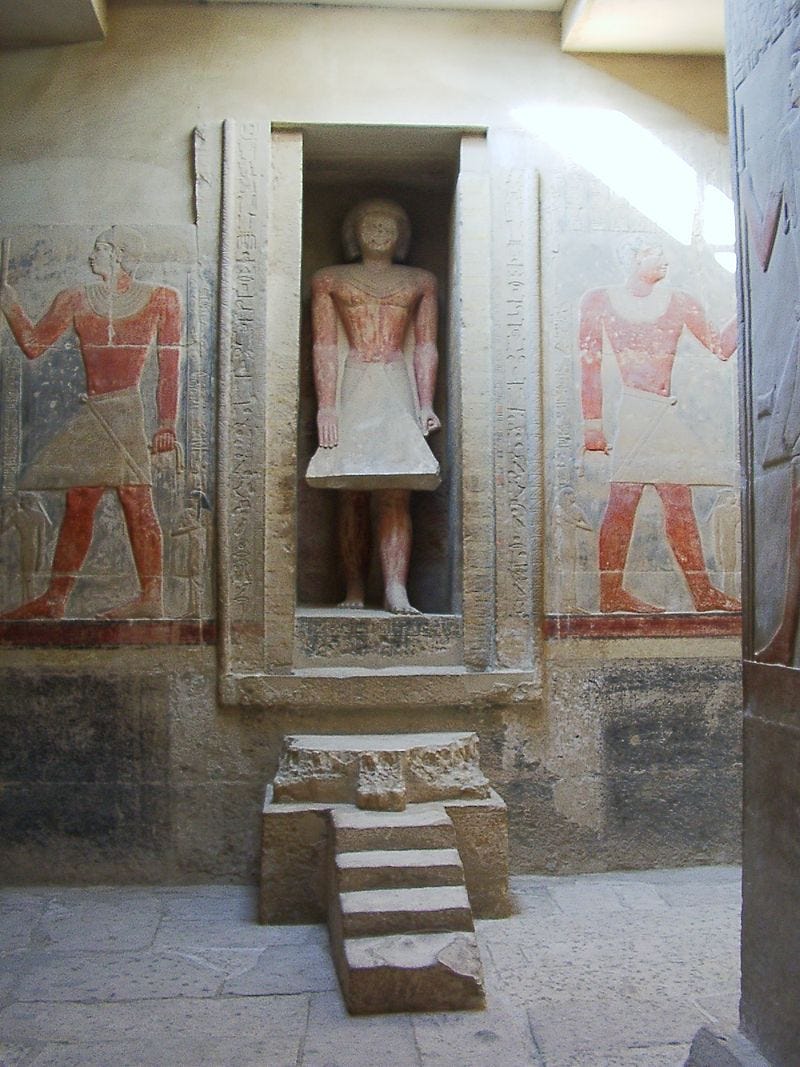

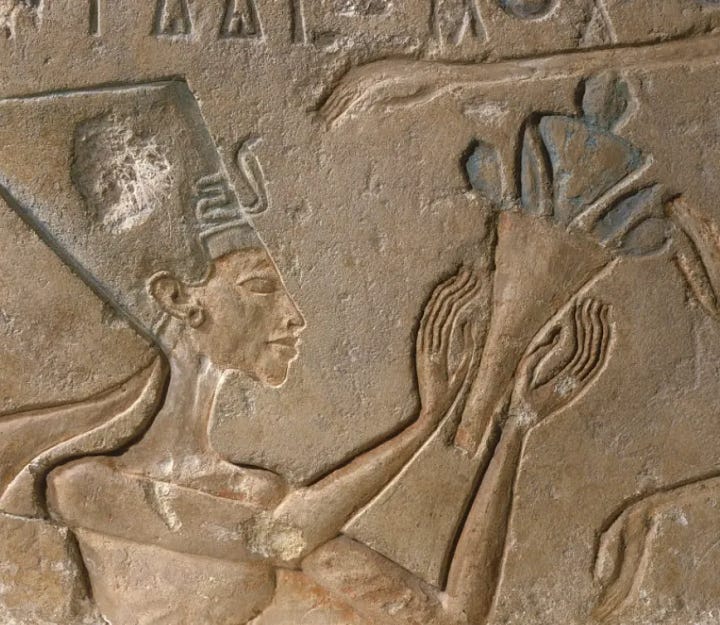

Stylised Old Kingdom formality and canonicity

We’ve all got a pretty good idea what ancient Egyptian art looked like. We think of stiff figures, usually with cartoon-like stylised iconographic depictions of the human figure, the torso turned fully toward the viewer and the head in full profile, the arms, legs and hands in stiff, almost ritualistic positions.

The scenes depicted are not intended as “time-traveller snapshots” of what you would see if you went back to the 22nd century BC with a Polaroid, but are abstracted symbolic, “canonical” images, often combining pictorial representations with written words in the form of hieroglyphic captions. The images are so stylised as to be not much more pictorial and representational than the hieroglyphs.

A brief flowering of New Kingdom naturalism: Amarna period: 1353 to 1336 BC

Egyptian art had remained canonical and static for an unimaginable 3000 years. Until…

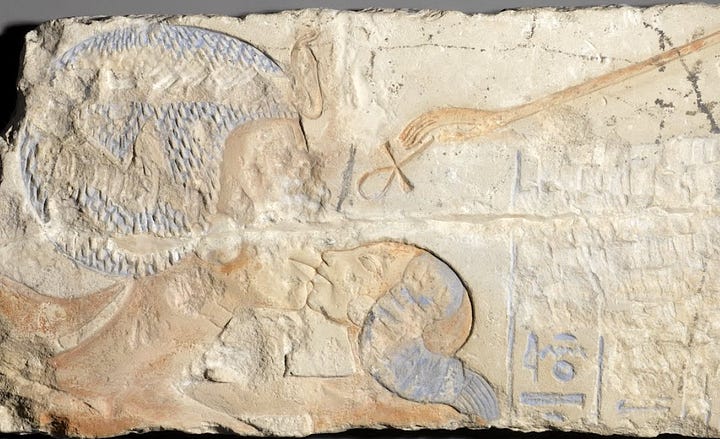

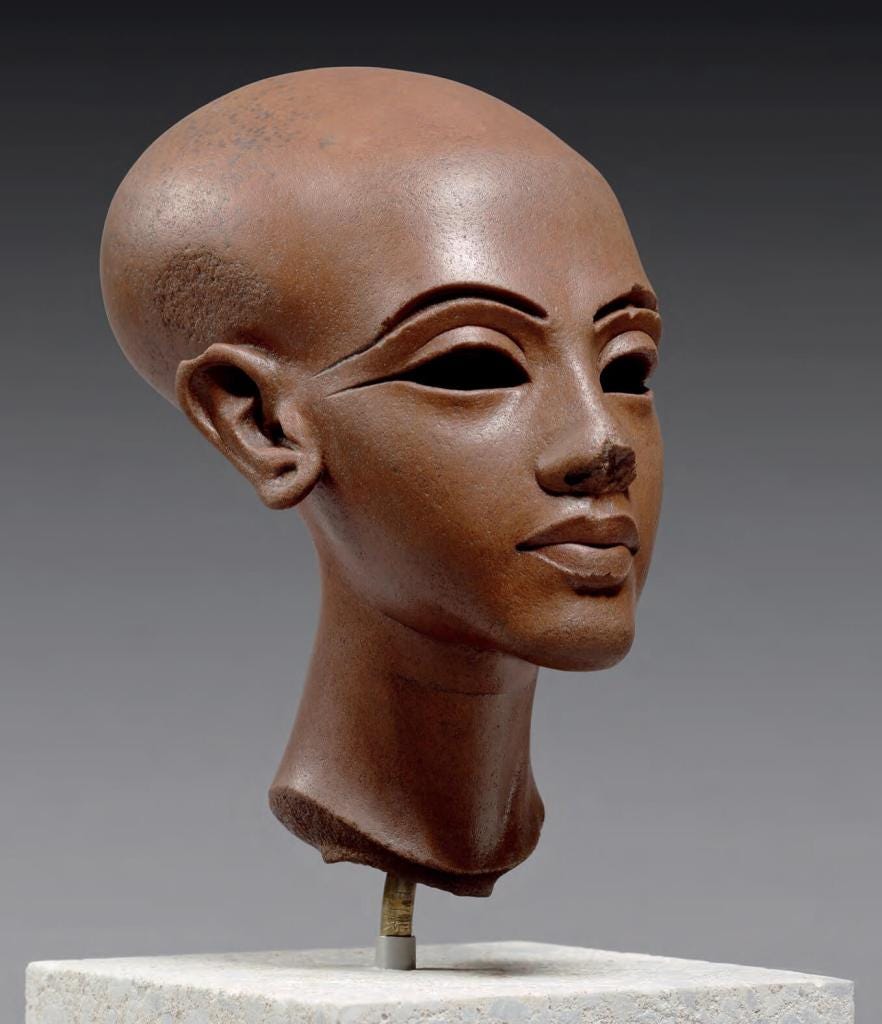

There was a brief moment - no more than 20 years - of naturalism in pre-Ptolemaic Egyptian art where these ancient canonical conventions of depicting the human figure were thrown off, and for perhaps the first time Egyptian artists created naturalistic human figures.

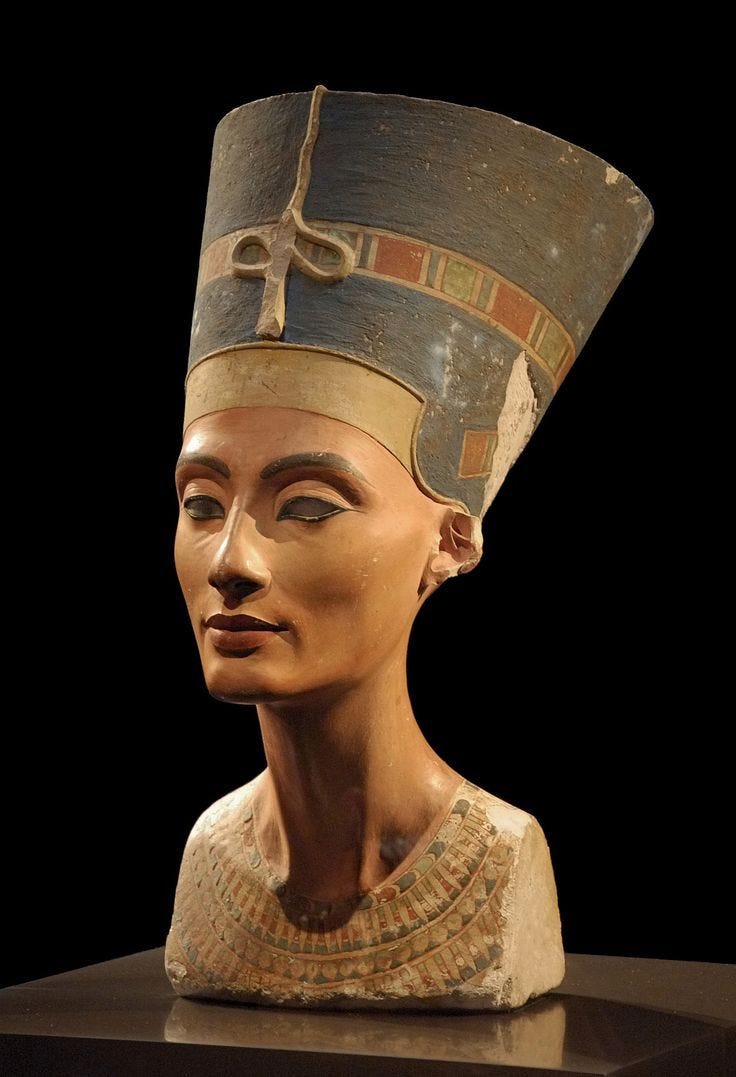

Pharaoh Akhenaten, (reigned c. 1353–1336 BC) the father of Tutankhamun, whose wife was Nefertiti, sponsored a revolution in Egyptian classical art as part of his religious reforms promoting the worship of the Aten (sun disc).

The Amarna2 artistic revolution included:

Focus on the Human Form: an idealised naturalism manifested in a new focus on portraying the human form in a more realistic, less static way. Artists depicted people with elongated limbs, slender builds, and sometimes even physical imperfections. Akhenaten himself was often portrayed with an elongated neck, protruding belly, and full lips – a stark contrast to the traditionally strong and muscular pharaohs.

Movement and Emotion: Amarna art incorporated a sense of movement and emotion. Figures were shown in more dynamic poses, and facial expressions hinted at emotions like tenderness and joy, especially in depictions of Akhenaten's family.

Nuance and Detail: Artists paid closer attention to details like musculature, wrinkles, and jewellery, adding a layer of realism not seen before. A famous example is the iconic bust of Nefertiti, Akhenaten's wife, which is considered one of the most beautiful portrait busts ever discovered from the ancient world.

The Egyptian Museum has a list of recommended further reading on this fascinating flourishing of Egyptian art, click here.

~

Stay tuned for our thrilling follow-up post for free subscribers: how Egypt influenced the Christian art world in Byzantium

Shared Techniques: Egyptian artists had always been at the forefront of developing materials technologies, with mastery of synthesizing pigments, and media. Fresco, encaustic and egg tempera were well known to them, and these were exported around the Roman world, and inherited by Byzantium.

Panel Painting Tradition: Both the artistic style and technical aspects of Fayum portraiture are easy to trace into later Christian art. Both belonged to the broader tradition of panel painting, a significant art form in the classical world that continued to influence artistic styles in the Byzantine and Coptic traditions.

Focus on the Head and Shoulders: Similar to Fayum portraits, early Christian icons often focused on head and shoulder depictions of religious figures, including, as we’ve seen, the “classic” Byzantine 3/4 profile.

And we’ll visit the Coptic monasteries of Wadi Natroun and finally St. Catherine’s in Sinai, where the most important icon of the Christian world still resides.

Roman rule in Egypt lasted from 30 BC to 641 AD. It began with the conquest of Egypt by Roman forces in 30 BC, following the defeat of Mark Antony and Cleopatra at the Battle of Actium. It lasted all through the early Christian evangelism period until the Arab conquest by Muslims in 641.

Tel Amarna is named after the Arabic name for the hill that marks the place of Akhenaten’s new ruling city, called Akhetaten.

Really fascinating. I have always been struck by the realism of the Fayum portraits- as if each person is still alive and waiting to share stories. And I sure can see how these influenced later icon-making. Judging by the exquisite Nefertiti sculpture, it seems like realistic art was already there in addition to the more stylized art. I look forward to the next part!

Absolutely fascinating. I know nothing about Ancient Egypt, and this makes me want to learn more about it. Really looking forward to part 2!