There’s a lot of water imagery in the Bible. I mean, a LOT. It appears both literally and symbolically from the first page almost to the last:

“The earth was invisible and unfinished; and darkness was over the deep. The Spirit of God was hovering over the face of the water…”

to:

“And the Spirit and the bride say ‘Come!’ And let him who hears say ‘Come!’ And let him who thirsts come. Whoever desires let him take the water of life freely.”

Water pours out of the upper heavens and destroys the wicked world of men and washes the earth clean of their sins. The water of the Nile saves the life of Moses. Water gushes forth from a dry rock in the desert and quenches the thirst of the Israelites. Christ is baptised by John in the River Jordan, turns water to wine, walks on it in a storm and promises “living water” to the Samaritan woman at the well.

The Psalms, those poems of glory by which we enter into a dialogue with heaven, start the conversation talking about water and what it means - it is the living God:

Psalm 41 (42)

“As the deer longs for the fountains of waters, so shall my soul dwell upon thee, O God.

My soul thirsts for the living God; When shall I come and appear before the face of God?

These ideas have long provided inspiration to sacred artists. But try googling the opening line today, and you get this:

The thing is, it’s not just a metaphor. Talking about “living water” is not just a poetic way of saying it will be very nice in heaven. “Isn’t that lovely that the pretty deer get something to drink in heaven…”

I’ve said that the main difference between eastern Christian sacred art and its western counterpart is that the former speaks a purely symbolic language, that has to be very specific, to convey particular theological ideas. Like any language it can convey truth or error, and so it is carefully guarded, which is why the iconographic tradition is commonly criticised as somewhat staid and static, unimaginative.

Western sacred art effectively broke away from the grammar and syntax of this symbolism at the time of the Renaissance, favouring instead an effort to create a kind of literalist snapshot of the past. It concerned itself wholly with representing the natural world - that is, things and people as you would have seen them in physical space, as if you were being transported back in time through the picture frame.

The Theotokos, for instance, was stripped of her multitude of identifying symbolic colours, garments, accoutrements, gestures and poses, and reduced to a pretty woman with a baby. Often later depictions of the Virgin would dispense even with standard items like the halo or nimbus that in traditional symbolic art informed the viewer that the person was a heavenly citizen, a saint or angel or God Himself.

To convey the theological truths being depicted, the viewer had to already know, and apply what he knew to the image.

And maybe squint a bit…

The Renaissance painters and those who followed them moved very quickly from conveying theological truths - the invisible supernatural realities - in symbolic language to depictions of mere natural reality, the physical world in time as it looks to the human eye. It’s clear that by the Baroque the religious significance was sidelined and the aim was to show off the painter’s skill at depicting lifelike images. This, quite simply, is no longer sacred art. It is secular art with a (vaguely or nominally) religious subject.

Apart from a multitude of philosophical issues this change brought about, one effect of the shift to naturalism is that it became nearly impossible to depict the more abstract, metaphorical or symbolic - poetic - passages of Scripture.

Living water

The “living water” thing is not a mere poetic metaphor, it’s a symbol, it’s a way of describing a real, specific thing: the Holy Ghost, the source of eternal life.

John 7: 37 - 39:

On the last day, the climax of the festival, Jesus stood and shouted to the crowds, “Anyone who is thirsty may come to me! Anyone who believes in me may come and drink! For the Scriptures declare, ‘Rivers of living water will flow from his heart.’” (When he said “living water,” he was speaking of the Spirit, who would be given to everyone believing in him. But the Spirit had not yet been given, because Jesus had not yet entered into his glory.)

From His heart: the heart that will be pierced through at the crucifixion, from which blood and water will burst.

And the context of the comment will be even more enlightening. He made this promise during the discourse at the Feast of Tabernacles, the Jewish festa that commemorated the wandering of the Israelites in the desert, during which water was mixed with wine and poured out in a ceremony in the Temple of Jerusalem to symbolise the water that flowed from the rock struck by Moses.

Exodus 15: 23 -25

“They walked three days into the desert and they did not find water. They arrived at Marah, but they could not drink the waters of Marah for they were bitter. That is why the place was called Marah. So the people murmured against Moses, saying, “What will we drink?” He called upon the Lord, who showed him a tree. When he cast it into the water, it became sweet.”

The Fathers interpreted this passage to refer to the bitterness of life in the fallen world without the grace of Christ. The tree that is thrown into the bitter, unbearable water is the cross of Christ.

And the culmination of all this is found in Revelation, in its symbolic description of what heaven will be like:

Rev. 21:

Then I saw “a new heaven and a new earth,” for the first heaven and the first earth had passed away, and there was no longer any sea. I saw the Holy City, the new Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God, prepared as a bride beautifully dressed for her husband. And I heard a loud voice from the throne saying, “Look! God’s dwelling place is now among the people, and he will dwell with them. They will be his people, and God himself will be with them and be their God. ‘He will wipe every tear from their eyes. There will be no more death or mourning or crying or pain, for the old order of things has passed away.”

He who was seated on the throne said, “I am making everything new!” Then he said, “Write this down, for these words are trustworthy and true.”

He said to me: “It is done. I am the Alpha and the Omega, the Beginning and the End. To the thirsty I will give water without cost from the spring of the water of life.

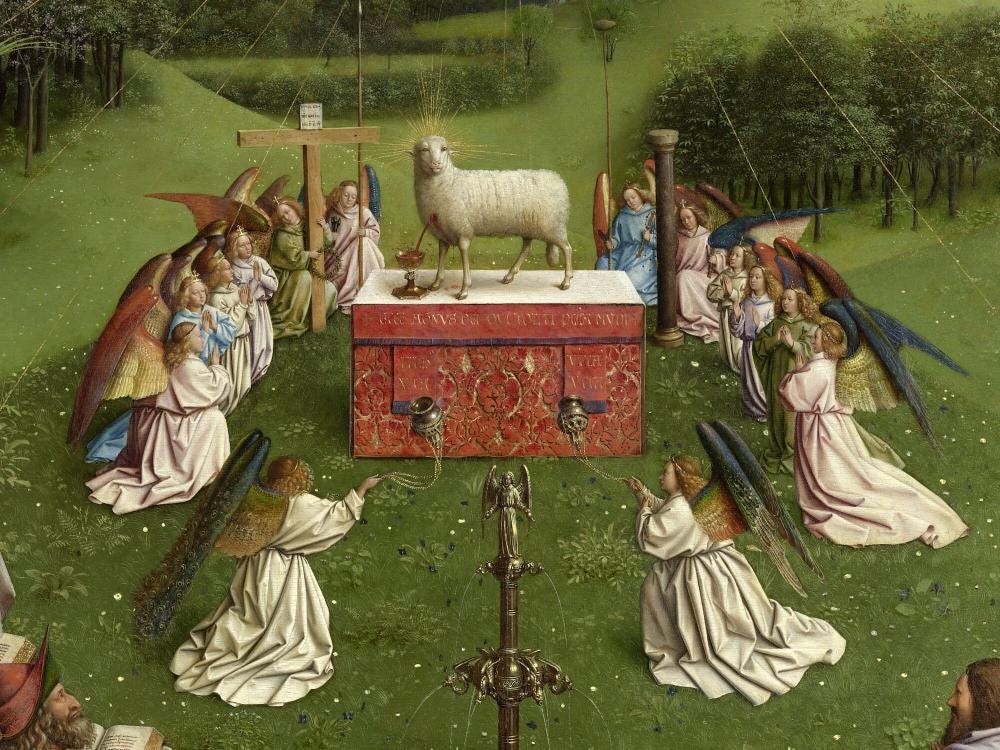

All this, all these layers of meaning, these divine promises of eternal life, of being brought out of the desert of sin and suffering and having all bitterness made sweet, are encapsulated in the icon above that shows in symbolic language what all this will be.

.

What does heaven look like?

The Ghent Altarpiece - one of our principal treasures of western sacred art - sits just at the moment when European painters started moving away from symbolic visual language and toward naturalism. This coincided with the change from egg tempera to oils as a medium, and the latter’s ability to create more realism captured the imagination of western painters and patrons.

So a painting like this1 is using the old traditional Christian symbolic language, but "translating" it into the new naturalistic, literalist style. It's easy to see how a simple person looking at this great work at Mass every day would come away with the idea that this is literally what you would see with your eyes in heaven, instead of a visual depiction of the symbolic description of heaven found in Revelation.

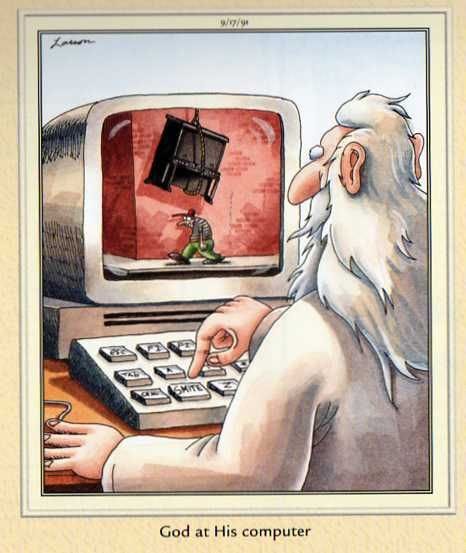

And that’s what we’ve got now. The popular image of heaven of people sitting about on clouds, wearing white robes and maybe doing a little light harping from time to time, to while away eternity, has become as ubiquitous in the popular imagination as the picture of a bearded God the Father looking for excuses to push the “smite” button; this all comes from western naturalistic sacred art.

A believing Christian, if asked, would of course immediately dismiss such things as silly or at least incomplete. He would say something like, “Oh, you know. That’s just the movies. Heaven is unknowable… ‘eye has not heard nor ear seen’ and all that…Erm…” But western Christians are reduced to hemming and hawing, because we no longer have a language to describe the things we believe and hope for. We can’t believe in the clouds and harps, and podgy flying babies, but what else do we have for a visual vocabulary?

And it’s not too hard to figure out where we got it.

So, what does heaven look like, anyway? Well, “look like” isn’t something we can answer. But the Bible is full of imagery about what it will be like. And it is the job of sacred art to show us what those images mean, not as literal depictions of things we can see with our eyes but as divine realities. Its job is to show us, in symbolic not literal, language what eye has not seen.

But before we lost the sense of what we were doing with sacred art, we knew one thing for sure: it would have Christ at the centre.

Thanks for reading to the end. If you would like to see some of my “real” work, my painting, you can click on my Ko-Fi page, Hilary White; Sacred Art, here, where you can also drop a few coins in the tip jar if you enjoyed this.

Right now this blog is not directly monetised, and painting and donations from supporters and patrons are my sole source of income. If you sign up to be a monthly patron, you can join my private patrons-only chat group on Signal.

You can also follow me at Hilary White: Sacred Art on Facebook and see a little hint of the Old Hilary White; journalist being cranky on Twitter too. Many thanks to all who have contributed to make it possible to keep working - the “struggling artist” thing doesn’t last forever, but it is a struggle for a while. Stay tuned.

The section I’ve copied here is only a small portion of this magnificent masterpiece. See the restoration work here.

John 7: 37-39 etc. is read on the Feast of Pentecost because Pentecost is "...the last day, the climax of the festival... ". 50 days of celebrating the Risen Christ Who ascended into Heaven. That's why in the Byzantine Tradition we don't kneel during Paschaltide.

At Vespers on Pentecost, there are 3 special "kneeling prayers" . After that, we can resume kneeling in prayer.

"The “living water” thing is not a mere poetic metaphor, it’s a symbol, it’s a way of describing a real, specific *thing*: the Holy Ghost, the source of eternal life.

The Holy Ghost is the Third Divine Person of the Holy Trinity. He is *not* a "thing".

Otherwise 👍