The Icon of the Transfiguration, Iconoclasm and Charlemagne

Part 2 of our exploration of the Carolingian Renaissance and what it all meant

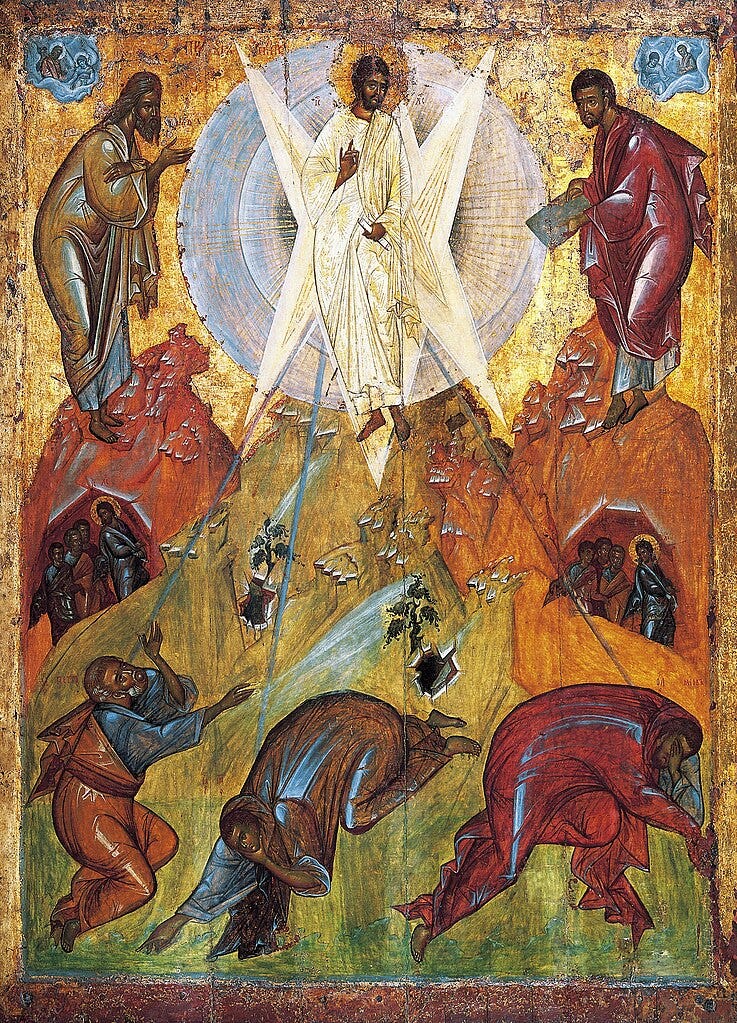

Transfiguration and Theosis - “transformation into His own likeness…”

This Tuesday in both the western and eastern Christian church was the Feast of the Transfiguration, yet another of the great Christological feasts whose significance we in the west have nearly forgotten. Today I’m going to talk about some reasons we might have lost that memory and why this particular feast, and its iconographic prototype, could lead to a mighty transformation for all of us.

Fellow liturgical art-enjoyer, Amelia Sims McKee wrote this week about this mosaic on her Substack, Art for the Liturgical Year:

It is especially fitting that the Transfiguration should take pride of place in the basilica on Mount Sinai—the mountain where God appeared to Moses and Elijah. Church Fathers understood the Transfiguration to fulfil these Old Testament theophanies. While God appeared to Moses in a burning bush and to Elijah in the “still, small voice” outside the cave at Mount Horeb, he revealed himself to the apostles in the Transfiguration face to face, revealing his glorified humanity.

In today’s post for all subscribers, we’re going to take a closer look at the relationship between iconography and what they call “divinisation” in the eastern Church, and the long term effects of some of the great movements of history that brought us the “Carolingian Renaissance” and how it all affected Christian theology. This is part of our series on Carolingian art but also dives into the very meaning and purpose of Christianity itself, and how we might begin to recover some of our shared ancient mystical tradition.

The Sacred Images Project is a reader-supported publication where we talk about Christian sacred art, the first 1200 years. It’s my full time job, but it’s still not bringing a full time income, so I can’t yet provide all the things I want to and am planning for. You can subscribe for free to get one and a half posts a week.

For $9/month you also get the second half of the Goodie Bag, plus a weekly paywalled in-depth article on this great sacred patrimony, plus extras like downloadable exclusive images, ebooks, mini-courses, photos, videos and podcasts (in the works).

The other way you can help support the work is by signing up for a patronage through my studio site, where you can choose for yourself the amount you contribute. Anyone contributing $9/month or more there will (obviously) receive a complimentary paid membership here.

You can also take a scroll around my online shop where you can purchase prints of my drawings and paintings and other items.

What was the Transfiguration for? Why is it still important now?

“As time goes by you may be in danger of losing your faith. To save you from this I tell you now that some standing here listening to me will not taste death until they have seen the Son of Man coming in the glory of his Father." Moreover, in order to assure us that Christ could command such power when he wished, the evangelist continues: ‘Six days later, Jesus took with him Peter, James and John, and led them up a high mountain where they were alone. There, before their eyes, he was transfigured. His face shone like the sun, and his clothes became as white as light. Then the disciples saw Moses and Elijah appear, and they were talking to Jesus.’”1

…It is for us now to follow him with all speed, yearning for the heavenly vision that will give us a share in his radiance, renew our spiritual nature and transform us into his own likeness, making us for ever sharers in his Godhead and raising us to heights as yet undreamed of.

I thought it was significant that the creators of the American Protestant/Mormon television show, The Chosen, when asked about it by Orthodox Christians, were reportedly completely baffled why anyone would be interested in seeing a depiction of the Transfiguration in their show. It’s just unimportant to the Protestant mindset, oriented as that is toward the mere verbal, moral teachings of Christ, a good deal more than toward His person and His nature. The modern (Protestant) Christian mind is deeply materialistic compared to that of our spiritual ancestors. It has almost entirely forgotten the purpose of Christianity itself, the mystery of the radical personal transformation the Byzantine Christian world calls “Theosis”. It is this transformation that the story of the Transfiguration and its icon represents.

Protestants and other modern western Christians are shocked and somewhat scandalised by terms like “divinisation” for that process of deep spiritual alteration, and like to ignore the places in Scripture that present it to us. Modern Latin Catholics, having almost entirely forgotten the ancient mystical Christian tradition of the pursuit of the Transforming Union, have been deeply influenced in Anglo countries by Protestantism’s “low Christology.” This is a problem the heavy-handed bureaucratisation and institutionalisation of all aspects of Catholic life since the Council of Trent has done nothing to help2.

To put it simply; in the west we have effectively forgotten what Christianity is for. So it should be hardly any wonder that we have lost all interest in the iconographic tradition that supported those ancient mystical goals.

How did it happen? Well, we have to go back a way in history…

How did we start to forget? Christendom divided

One of the things I’m trying to do with all this is create connections between historical events and movements that are too often looked at in isolation, without larger context. The “Carolingian Renaissance” that we talked about earlier, occurred within a broader historical context that included some pivotal developments in the Byzantine Empire. And the start of the Carolingian in the west marked the beginning of the ongoing divergence that would lead finally to the Great Schism between the eastern and western parts of Christendom.

Timeline of Iconoclasm

Islamic conquest of Damascus (634): The city was a major centre in the Byzantine Empire and its capture marked a key victory in the early Muslim campaigns in the Levant, which eventually led to the complete control of the region by Muslim forces and the beginning of the Islamic presence in Syria, which would soon expand further into the Byzantine heartlands, finally leading to its complete overthrow in 1453.

First Iconoclasm (726-787): Initiated by Emperor Leo III, who issued edicts against the veneration of icons, in part due to pressure from Islam, leading to widespread destruction of religious images and persecution of iconodules.

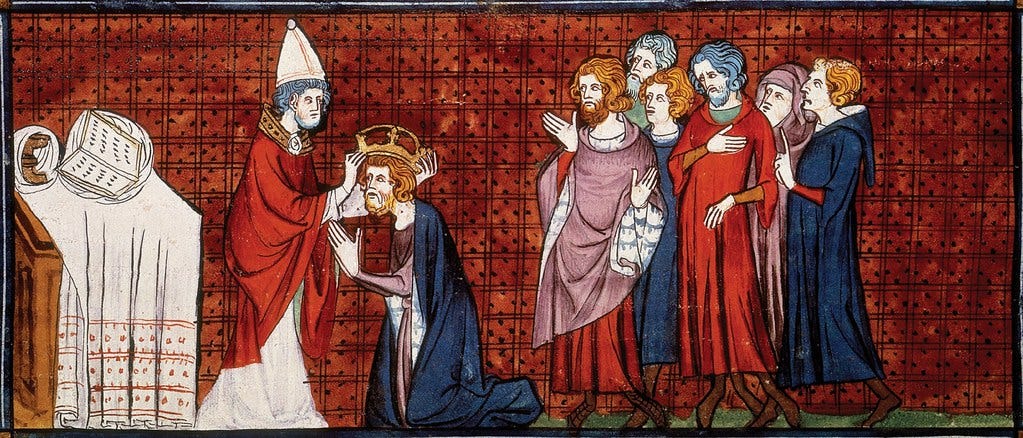

Christmas Day in 800: Pope Leo III crowned Charles, King of the Franks and Lombards, in Rome as Emperor of the Romans, symbolically reviving the Western Roman Empire.

Second Iconoclasm (814-842): After a period of restoration of icons under Empress Irene, Emperor Leo V reinstated iconoclasm.

Second Council of Nicaea (7873): The final defeat of Iconoclasm came with its condemnation as a heresy by the Second Council of Nicaea. This event is celebrated in the Eastern Churches as “The Sunday of the Triumph of Orthodoxy,” on the first Sunday of Great Lent.

8th & 9th century history of eastern and western Christendom crammed into the smallest possible nutshell

At the time of the coronation of Charlemagne, the Byzantine Empire was embroiled in and distracted by the iconoclastic controversy. Why did the pope pick this precise moment? While the Byzantine Empire still existed in Constantinople, their situation was far from stable and they weren’t very interested in what the pope of Rome had to say about anything. Leo, under various pressures of his own, crowned the already-successful Charles4 to be an emperor over a western empire that would be independent of Constantinople and under papal influence or control.5

Byzantium remained influential in Italy, however. Under Emperor Justinian, they had reconquered parts of Italy from the Ostrogoths in the 6th century, with the Exarchate of Ravenna as the capital of Byzantine Italy until its fall to the Lombards in 751. Parts of the peninsula remained under Byzantine rule until the last stronghold, Bari, fell to the Normans in 1071.

The coronation of a new emperor for a new empire was taken by Constantinople, rightly, as a challenge the Byzantine claim of being the sole continuation of the Roman Empire and exacerbated the East-West divide. The Byzantine emperors, including Irene, the empress who ended the first Iconoclastic Crisis, viewed it as an illegitimate usurpation of their authority.

Irene was the first woman to rule the Byzantine Empire as sole ruler and Leo III, seeking to strengthen the Papacy’s position, claimed that Irene’s rule was illegitimate as a justification for crowning Charlemagne. By this claim against Irene he was able to declare that the imperial title was vacant, and so could be bestowed by his own authority on Charles of the Franks.6

Iconoclasm, that had been promoted by the Byzantine state, had not really affected the western half of Christendom, since the Italian peninsula had not been under Byzantine rule for some time. Western Christendom was also as yet little affected by the incursions of Islam. This is why the pope had taken little interest in the crisis that had seen open persecution of Christians by the Byzantine state. The pope of the time did not even attend the 2nd Council of Nicaea, sending delegates instead and issuing a letter affirming its findings after the fact.

One of the upshots of this separation was to leave Constantinople largely on its own in the struggle with Islam - a centuries long war it eventually lost. In the 7th and 8th centuries, the rapid expansion of the Islamic Caliphates significantly altered the political and cultural landscape of the Mediterranean world. Islamic conquests of the Levant, North Africa, including the crucial Christian cultural centre of Egypt, pushed Byzantine Christianity into a marginal position and suppressed its cultural influence.

While the Carolingian period in the west played a key role in spreading Christianity to the Saxons, Slavs, and other pagan groups, the memory and prominence of certain Christian mystical doctrines that remained central in the east, started to be sidelined.

With the loss of the East the gradual loss of monastic mysticism

We’ve talked a lot about the divergence of eastern and western Christian art in the later Middle Ages, but the draining of mysticism from our art started well before. Christian monasticism - effectively a massive field test of Christian mystical theology - had been established in Italy from late Antiquity. It was already well established by the time a teenaged Benedict left Nursia to study for his public service exams in Rome7.

While the mystical theology of the east - including the concept of Theosis as the goal of the Christian life itself - was carried forward and preserved by monks into our own time, these ideas receded in the west. Eventually the institution of the western church got hold of monasticism in the west and started its transformation into a temporal - political and economic - power, pushing its original purpose into the background.

The history of European monasticism has ever since been a chronicle of a perpetual pendulum swing between worldly corruption and spiritual reforms. But during all these movements of monks and theologians, the idea that the contemplative life, mysticism and the goal of the Transforming Union, was just for monks and a few specially blessed souls, became generally accepted, and the whole business largely forgotten.

And by the time of the third explosion of iconoclasm once again in the 16th century, with the Protestant Revolution, these materialist movements had entirely erased our spiritual memories. By then, the very idea of giving one’s life for the sake of icons would have been - and continues to be - incomprehensible to any western Christian.

That’s enough for now. Next week we’ll talk more about Iconoclasm itself, how it started and by whom, and why it’s bad. In reality it is not about the images, but about the nature of Christ, His Incarnation. Iconoclasm is an offshoot of the Christological heresies, combined with politics, specifically regarding the Byzantine conflict with Islam. And we’ll take a closer look at how the same Christological heresies were subtly at work in the various philosophical movements that led up to the Protestant Revolt, and their destruction of Christian images and, crucially, why Latin Christendom failed to stop it.

Excerpt from “A Sermon on the Transfiguration of Our Lord”. Athanasius of Sinai was a Greek writer, priest and abbot of Saint Catherine's Monastery on Mount Sinai. Died some time in the early 8th century.

To say nothing of the catastrophe of the Second Vatican Council, and all that followed it. But we’ll leave that for now.

Corrected. I said it was 843, and I’ve no idea why. Every single source says 787, so I’ve no idea why I got the date wrong. And it’s something like the second or third time too. Weird. Sorry.

Charles seemed a pretty good bet to create some political stability, since he was already the one who had united the Frankish kingdoms and conquered the Lombards in 774. Nothing succeeds like success.

This of course touched off a struggle between the western Emperor and the papacy over who got to do what, that was going to last another 300 years. But we can save the Guelphs and Ghibellines for later.

Irene was eventually deposed in 802 and her successor, Emperor Nicephorus I, initially refused to recognize Charlemagne’s imperial title. In 812, during the reign of Michael I Rangabe, the Byzantine Empire formally recognized Charlemagne as “Emperor,” but with the distinction that he was not “Emperor of the Romans,” a title reserved for the Byzantine ruler. This compromise allowed both empires to maintain their prestige while avoiding direct conflict.

St. Benedict and his twin sister Scholastica are traditionally held to have been part of the “gens Anicia,” a prominent and wealthy patrician Roman family with significant influence. As the eldest son Benedict would have been sent to Rome for the equivalent of college to prepare for a career. He would have got there just in time to see Theodoric the Great, king of the Ostrogoths (an Arian, though a tolerant one) who conquered Italy in 493 AD, establishing the Ostrogothic Kingdom.

Timeline of Iconoclasm

Islamic conquest of Damascus (634): The city was a major centre in the Byzantine Empire and its capture marked a key victory in the early Muslim campaigns in the Levant, which eventually led to the complete control of the region by Muslim forces and the beginning of the Islamic presence in Syria, which would soon expand further into the Byzantine heartlands, finally leading to its complete overthrow in 1453.

First Iconoclasm (726-787): Initiated by Emperor Leo III, who issued edicts against the veneration of icons, in part due to pressure from Islam, leading to widespread destruction of religious images and persecution of iconodules.

Christmas Day in 800: Pope Leo III crowned Charles, King of the Franks and Lombards, in Rome as Emperor of the Romans, symbolically reviving the Western Roman Empire.

Second Iconoclasm (814-842): After a period of restoration of icons under Empress Irene, Emperor Leo V reinstated iconoclasm.

**Second Council of Nicaea (843):** The final defeat of Iconoclasm came with its condemnation as a heresy by the Second Council of Nicaea. This event is celebrated in the Eastern Churches as “The Sunday of the Triumph of Orthodoxy,” on the first Sunday of Great Lent.

***

The Second Council of Nicaea was in **787**. The Sunday falling between Oct. 11 - 17 is the Sunday of the Fathers of the Seventh Ecumenical Council (Nicaea II) in 787 AD.

The final restoration of the Holy Icons is in 843.

So the correct timeline would look like this:

Timeline of Iconoclasm

Islamic conquest of Damascus (634): The city was a major centre in the Byzantine Empire and its capture marked a key victory in the early Muslim campaigns in the Levant, which eventually led to the complete control of the region by Muslim forces and the beginning of the Islamic presence in Syria, which would soon expand further into the Byzantine heartlands, finally leading to its complete overthrow in 1453.

First Iconoclasm (726-787): Initiated by Emperor Leo III, who issued edicts against the veneration of icons, in part due to pressure from Islam, leading to widespread destruction of religious images and persecution of iconodules.

Second Council of Nicaea (787): The condemnation as a heresy by the Second Council of Nicaea.

Christmas Day in 800: Pope Leo III crowned Charles, King of the Franks and Lombards, in Rome as Emperor of the Romans, symbolically reviving the Western Roman Empire.

Second Iconoclasm (814-842): After a period of restoration of icons under Empress Irene, Emperor Leo V reinstated iconoclasm.

Final defeat of Iconoclasm (843): This event is celebrated in the Eastern Churches as “The Sunday of the Triumph of Orthodoxy,” on the first Sunday of Great Lent.

***

In reality it is not about the images, but about the **nature** of Christ, His Incarnation.

Our Lord Jesus Christ is one Divine Person with **two natures**, Divine and human, in the unity of His Divine Person without confusion, without change, without division, without separation. (Council of Chalcedon, the Fourth Ecumenical Council in 451 AD).

Full dogmatic definition of the Council of Chalcedon:

Following the holy Fathers we teach with one voice that the Son [of God] and our Lord Jesus Christ is to be confessed as one and the same [Person], that he is perfect in Godhead and perfect in manhood, very God and very man, of a reasonable soul and [human] body consisting, consubstantial with the Father as touching his Godhead, and consubstantial with us as touching his manhood; made in all things like us, sin only excepted; begotten of his Father before the worlds according to his Godhead; but in these last days for us men and for our salvation born [into the world] of the Virgin Mary, the Mother of God according to his manhood. This one and the same Jesus Christ, the only-begotten Son [of God] must be confessed to be in two natures, unconfusedly, immutably, indivisibly, inseparably [united], and that without the distinction of natures being taken away by such union, but rather the peculiar property of each nature being preserved and being united in one Person and subsistence, not separated or divided into two persons, but one and the same Son and only-begotten, God the Word, our Lord Jesus Christ, as the Prophets of old time have spoken concerning him, and as the Lord Jesus Christ has taught us, and as the Creed of the Fathers has delivered to us.

Source: New Advent

Hope this helps. Otherwise <3 .

I sent my children to a Protestant Christian school, and in their many years of Bible study, they never once had any discussion at all on the Transfiguration. If it even got any mention, it was only to say "Well, Jesus was just proving he was God, in case they doubted." Move along, nothing to see here.

In many Orthodox countries, The Transfiguration is considered the 3rd most important of the Feasts of the year, falling only behind Theophany (Christ's baptism in the Jordan), and Pascha itself (Christmas's rise in prominence is a recent and very very Western thing). The Feast is considered theologically profound as not only did Christ reveal Himself as God, but revealed Himself as the God of the Living - Elijah had been taking bodily into Heaven, and Moses was perhaps also. Moreover, there is a line of speculation in the hymnography about the moment as being also when Moses beheld God's passing glory, in a moment outside of time itself.

St. Gregory Palamas pondered the Light of Tabor, and taught that the truly humble and prayerful might even be granted this same experience of Christ in the Uncreated Light (what I think you might refer to as the "Beatific Vision"). Disputes over Palamas's teachings were to be another major rift between East and West in the 1300s.