The Mysterious Frescoes of Castelseprio

A lost ancient treasure of Christian Art

An artefact out of time

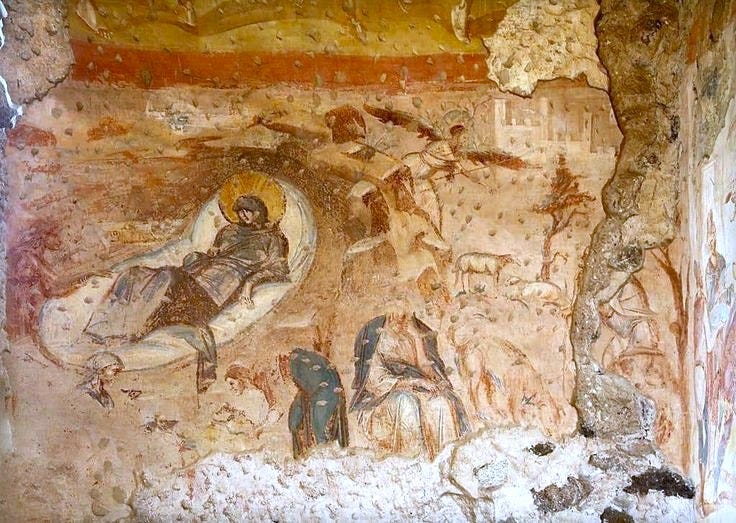

It might seem surprising that this fresco of Christ Pantocrator, discovered in the apse of a small obscure church in the north of Italy, is so unusual that it caused a major re-write of the art-history timeline.

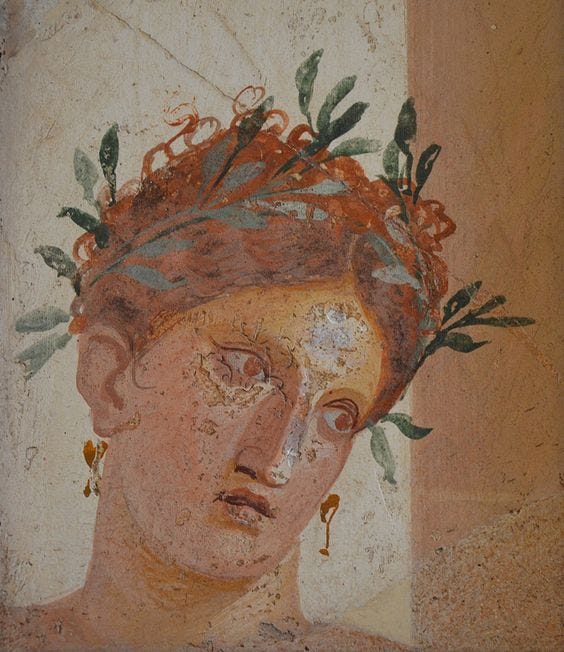

It looks like any early Byzantine image that we’ve seen hundreds of times: serene, otherworldly, with the face symmetrical with classical proportions, modelled with lights and darks to give the impression of lifelike three-dimensionality. But at the same time, we can see it is stylistically different: the softness of the facial modelling, the natural fall of the hair, the subtly rendered shadow beneath the chin, the piercing gaze and human expression.

In fact, it immediately reminds me in its naturalism of the frescos discovered at Pompei and Herculaneum. It might not be surprising to find that it dates to the earliest paleo-Christian period, when Roman standards were still in use.

But that would be the wrong guess.

In today’s post for all subscribers, we will explore the treasure left forgotten in a tiny church in the forests of Lombardy. Hidden for centuries beneath layers of plaster, the exceptionally beautiful and lively Byzantine frescoes of Castelseprio challenge everything scholars thought they knew about Western art of the early middle ages - the time of the Lombard Kingdom, Carolingian and Ottonian empires.

Were they painted by a wandering Byzantine master, or do they reveal a local tradition that quietly preserved the grace and theology of late antique sacred art?

No one knows…

At The Sacred Images Project, we explore Christian life, thought, history, and culture through the lens of the first 1200 years of sacred art. This publication is entirely supported by readers — no ads, pop-ups or distractions — just thoughtful work, funded by your subscriptions.

While The Sacred Images Project has grown into my full-time work, we're now building toward an even richer, multi-layered platform, with plans for e-books, mini-courses, videos and eventually podcasts and more. Your support helps make this expansion possible.

If you’d like to follow along, you can subscribe for free and receive a weekly article exploring the treasures of Christian history, culture, and sacred art..

Paid subscribers ($9/month) receive a second, in-depth article each week, plus additional exclusive posts featuring in-person explorations, high-resolution downloadable images, and more.

If you believe in the importance of preserving and deepening our sacred patrimony, I hope you’ll consider becoming a subscriber today.

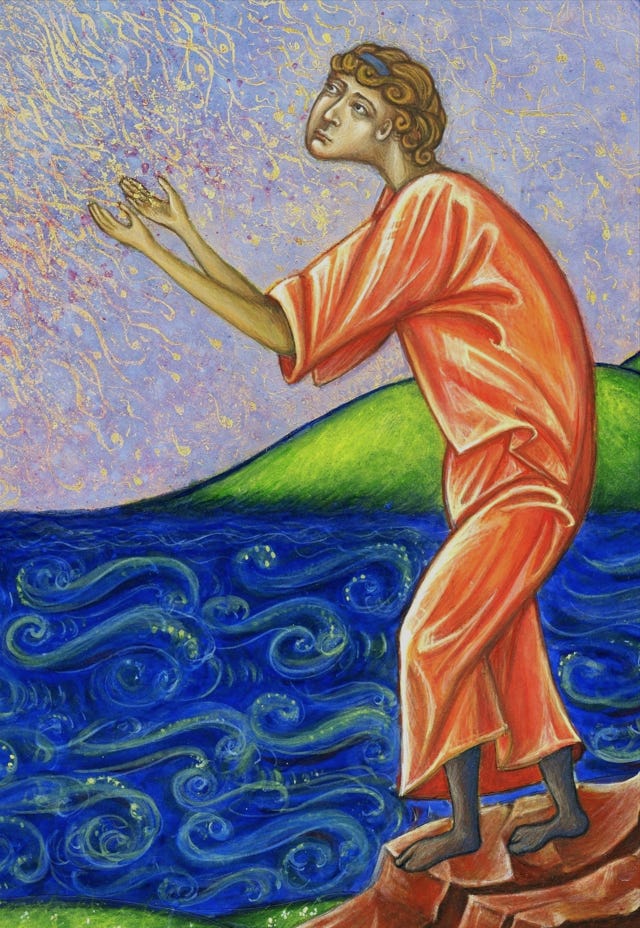

I’m happy to offer prints of this little figure, part of a painting - egg tempera and gold leaf - I did for a client in the contemporary Byzantine iconographic style. He is the speaker in Psalm 84, Quam Dilecta: “My soul longeth, yea, even fainteth for the courts of the Lord: my heart and my flesh crieth out for the living God.”

If you’d prefer to set up a monthly contribution in an amount of your choice, you can also do that at the studio blog, or make a one-off donation to help keep this work going. If you subscribe through my personal page, I’ll add you as a complimentary subscriber here. And thank you.

Lombard Byzantium in the woods

Well away from the bustle of modern Milan, in a remote wooded park near the town of Varese, is a forgotten Lombard stronghold with a chapel that, like many paleochristian and early medieval Christian structures, looks on the outside like nothing very special.

The Church of Santa Maria foris portas had been standing unobtrusive and mostly forgotten for centuries. But in the late 20th century, a treasure was discovered inside that was one of the greatest surprises of early medieval art in the west. It’s a cycle of Marian frescoes so refined and lively, and so unexpected, that their rediscovery shocked the world of academic art history and caused the timeline to be substantially reconsidered.

Castelseprio is now an archaeological park of mostly ruins in the foothills of the Alps, but in the 6th to 8th centuries it was an important strategic fortress of the Lombard kingdom, guarding the northern mountain approaches to Milan.

The Lombards were among the “barbarian tribes” who invaded - or we now more fashionably say “migrated” to - the Italian peninsula after the fall of the old empire, ultimately inheriting much of the rule of Italy. They crossed the Alps in 568, under their king Alboin, about a century after the establishment of the Ostrogothic kingdom that ended the old Western Empire. By then the Byzantines had already reconquered sections of the peninsula in the mid-6th century under Justinian.

Culturally, the Lombard kingdom blended their Germanic warrior culture with Roman administration and law, and local traditions. The Lombard elite gradually converted to Catholic Christianity1 and became significant patrons of monasticism, law and the arts. The Lombard kingdom ended when it was conquered by Charlemagne in his Frankish consolidation of Europe, but by that time, the end of the 8th century, they had created a rich and artistically complex Christian artistic legacy.

As was common in churches of that time, the frescoes at Castelseprio depict scenes from the life of the Virgin Mary. Drawn partly from apocryphal infancy gospels of the Virgin, these include the Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple, the Annunciation and the Visitation - all standard fare for Christian iconography. But these particular frescos are rendered with a grace, liveliness and fluidity utterly unlike most early medieval Western art. The style is classical and elegant, suggesting a deep familiarity with Eastern and Roman artistic traditions, perhaps even showing a direct influence from Constantinople. Scholars believe the artists were either trained in the East or belonged to a local tradition more ancient and cosmopolitan than had been previously assumed.

Some have suggested that the cycle was painted as a refutation of the Arian doctrines that were popular with Germanic tribes at the time. It could be an expression of the dual nature of Christ; the human nature, told in the scenes of the life of Mary, the Theotokos, and His divine nature as symbolized by the Christ Pantocrator.

These forgotten, lilting masterpieces of Byzantine art may be one of the clearest artistic bridges yet discovered between the East and West.

A lost and astonishing treasure

During the final years of World War II, Italian art historians began to investigate the church of Santa Maria foris portas more thoroughly. The ancient decoration of the church was hidden by whitewashing and paintings from the 15th and 16th centuries. Archaeologists removed layers of plaster on the apse and walls, to reveal a cycle of frescoes unlike anything else known from early medieval Italy.

Graceful, flowing figures with sophisticated modelling and classical proportions emerged, all rendered with startling delicacy and theological depth.

The discovery sent ripples through the academic art history world. Scholars were stunned not only by the beauty of the paintings but by their unexpected location and unfamiliar style.

No one has any idea who had painted them, and why they should have been found in such a remote place. The frescoes immediately became the focus of intense scholarly debate, with theories ranging from Greek monks fleeing iconoclasm to local artists trained in a forgotten tradition.

Even though the ages have damaged and fragmented them, these frescoes pulse with life. The figures gesture, turn, command and warn and interact with a fluidity and lifelikeness that seems centuries ahead of their time - or centuries behind. The grace of their movement, the softness of their modelling and the quiet emotiveness of their gestures and expressions suggest an artistic vision radically different from the rigid, monumental frontality that dominated most early medieval art.

Typical Lombard art

If we compare the Castelseprio frescos with other Lombard art of the period, we can immediately see just how anomalous and extraordinary they are. The typical visual culture of the Lombards was very much in line with the “barbarian” tribal forms; often abstract, symbolic or monumental, a blend of late Roman, Germanic, and early Christian styles.

The Diptych of Rambona, created perhaps 100–200 years after the Castelseprio frescoes, gives us a sense of Christian art in Italy of this time: abstraction, and symbolism isntead of realism, and iconic, hieratic frontality dominate. It is beautiful and theologically rich but nothing like what was produced for Castelseprio.

The Tempietto Longobardo, an 8th-century oratory in Cividale del Friuli, is one of the most refined examples of Lombard religious architecture and sculpture that survives. Carved stone reliefs of standing female saints show the priorities of the style: tall, elongated, frontal and abstracted.

The temporal coexistence of works like the Tempietto frescos and carvings, and the Diptych of Rambona, with Castelseprio challenges any simple story about the “decline” of art, or the narrative of a linear trajectory from less to more sophisticated, in the post-Roman world.

Who did them? It’s still unknown.

Scholars have debated for decades over the dating of these astonishingly Byzantine and Roman-looking frescoes. The images are modelled not with hard outlines, as in the typical Germanic styles, but with soft brushstrokes of light and shadow over a greenish base layer. Estimates have ranged widely, from as early as the seventh century to as late as the tenth. Recent analysis of the age of the original wooden roof beams of the church and thermoluminescence testing of clay building materials, placed its construction between 778 and 952. In 2012 dendrochronology was able to refine the estimate to between 928 and 980.

By then, northern Italy was no longer under Byzantine control, so this makes the very Byzantine visual language of Castelseprio all the more surprising. The evidence suggests that a tradition of Byzantine-trained artists survived in this pocket, far from the imperial centres.

Some scholars have suggested that the artistic style of Castelseprio (Castrum Sibrium to the Romans) could simply have been a survival of native artists of the area. There are no traces of Roman occupation on the castle hill, but much of the stone materials for the later fortress, some with Latin inscriptions, were reused in the walls. These have led scholars to the probable existence of a Romanised centre not far away. Archaeological investigations in the surrounding area show that Castelseprio fortress, built and expanded between the 1st c. BC and the 7th c. AD, was part of a dense network of Roman settlements that in the Late Antique period would have had their strategic centre at Sibrium.

It’s tempting to imagine a wandering Byzantine master arriving from afar, but I’d rather think that this style never completely vanished. Perhaps in this remote place, between ruined Roman towns and emerging medieval powers, a small group of artists had kept the old visual language alive for centuries.

Against the Arian version that was popular among Germanic and Frankish tribes at the time.

This is wonderful. I had never heard of these treasures and can see why the experts were flummoxed. It’s so delicate and the liberal use of white to indicate shading is very unique. It has an ethereal effect. Just love these examples you’ve given us. This must have been an amazing find during the end of the war, lifting spirits and creating wonder. I need to study these again, thank you for showing us so many treasures!

Amazing. Thank you!