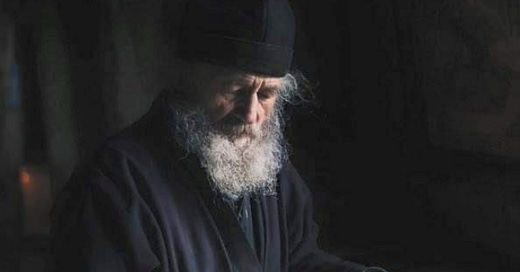

Part I of the desert and the pursuit of holiness: The way forward is through the desert

The Monastic Proposal: how to get there from here

Our first exploration into the world of monastic Christian thinking. As I said I’ll be posting some old articles I did years ago for another publication to get us warmed up. But in brief, it’s about what Christianity is actually for, how much of that has been forgotten or actually withheld, and how to get it all back.

We think it’s about programmes and activism, ideas and rebuilding institutions, or even building new churches. But those things presuppose something that we’ve already lost and has been lost for a long time; a thing its only possible to acquire one way.

The “Monastic Propositum” and the way through the desert

Originally published by The Remnant. July 2019. (Edited and expanded)

Believing Catholics talk a lot about finding ways to return the Church – and consequently the world – to the state of Christendom in the Age of Faith. We all have dreams of recreating the glories and certainties of medieval Christendom, and some of our most hopeful new monastic settlements - Norcia, Le Barroux, Clear Creek, the Benedictines of Mary in Missouri - are even going so far as to bring these dreams to reality in stone and mortar.

But much as we all love pointed arches and Gregorian Chant, is it possible that these dreams are leaving out a big piece of the puzzle? At least, in terms of rebuilding larger Christian civilisation, are we perhaps forgetting that the fruits of Christian culture -all those universities, hospitals and legal codes - presuppose a social, political and cultural context that made such physical manifestations possible?

Are we just modern men making medieval-looking palaces to live in, like LARPers dressing up for the Ren Faire? It’s natural for us to want a return of the greatness of Christendom of the 13th century, but is that something we even deserve in our current condition?

How did we get to Scholasticism and flying buttresses?

I don’t mean to say we shouldn’t build great physical structures where we can, or that money shouldn’t be spent on beautiful things; quite the opposite. But maybe we should pull the camera back a little. Where did these great cultural, social and philosophical treasures come from? How did we get to the point of even wanting to build Chartres and Notre Dame cathedrals? From what culture did Gregorian Chant derive? It took 182 years to build Notre Dame. What was the cultural condition of Christendom in 1163 that allowed the decision to be made to allocate such incredible resources in the first place? Are we in a situation now that is in any way comparable to that of the 11th or 12th century?

But then we have to ask, if we do want to return our entire civilisation to that level, if we want to see a revival of the great age of Faith, how did they get there? Where should we start? How far back do we have to rewind?

What historical Christian period most closely matches our own, an age of great achievement, moral strength and spiritual confidence, or an age of weakness, confusion, loss and persecution? The answer is perhaps not going to be much to anyone’s liking. The revival of Christendom can only be achieved the same way it was created in the first place.

Where did Christendom really come from?

The “propositum monasticum”

In a conversation by email, a well known Traditionalist monastic told me that whatever might come of these recent efforts to build neo-gothic monasteries, in our fierce longing for the age of Christianity’s greatness we could be putting the Gothic cart before the 3rd century desert monastic horse. He said we are in such a state of degradation we must go past even the roots of Christendom to the very seeds.

What did they have in 1163 that we don’t? Christendom was not built from nothing in the 12th century. It was a development from foundations laid centuries before in the ages of persecution and monastic heroism. Maybe it is not to Chartres and Notre Dame we should look, but to the Thebaid.

With our eyes full of the romantic glamour of the High Middle Ages we may have forgotten that the deserts of Egypt and Syria from the 3rd century were peopled with thousands of eremitical monks and nuns. These were Christians who had fled the consolations and protections of the world – including an abruptly legalised religion suddenly elevated to a State-sponsored institution – to strive for a heavenly way of living.

When, only a few decades later, a revival of persecution pushed these men and women out of their desert monastic cities they came providentially to spread that heavenly way of life into the rest of the Christian world of late antiquity1.

It was this, much more than the chaotic imperial politics of the early papacy2, that brought the living water to a European people thirsting desperately for Christ. These were people who were steeped in prayer, and whose ascetic life had given them a gift that was to set Europe on a path that would lead to the Christianisation of half the world.

Theosis: becoming like God

Just what really is “sanctification”? The Eastern Church - Orthodox and Byzantine Catholics - have retained very strongly the theological tradition of mystical theology that talks about how sanctification really works, what it is and how to get there. The core concept, in Eastern terminology, is “theosis”3:

In the East, it’s understood that theosis is not just the purpose of Christian monasticism, or even of the Christian life, but of human life entirely.

St. Athanasius “He became human that we might become divine.”

“Theosis is fundamental to the Christian life the Christian idea of salvation. The idea that we can be saved instantaneously with the flick of a finger; we ask Jesus to come into our hearts and we're saved or we obey the Pope and we follow a set series of do's and don'ts and suggestions and we find salvation, is foreign to Orthodoxy.”

The “propositum monasticum” – the radical, singular and irrevocable choice of a life dedicated wholly to Christ.

Personal dedication to union with Christ above all other things, a new idea

The foundation of monasticism is the personal dedication to union with Christ above all other things, an idea that would later be called the “propositum monasticum” – the radical, singular and irrevocable choice of a life dedicated wholly to Christ, a goal identical to theosis. Their idea was revolutionary for the ancient world, it must have looked to the pagan mind like a kind of mania, a godly madness that nothing could overcome.

A Byzantine Emperor4 may have decided to simply replace classical paganism with Christianity as the official state religion, but the two religious ideas - paganism and Christianity - are at root incompatible. Paganism never had very much to say to the individual about the moral life or salvation; Christianity had much to say to the state, but only gained that power through its prior claims on individual souls.

This inversion of the nature of religion was so radical, so completely unprecedented in all of known human history that it ultimately re-made the whole world. Christ does not want the cold, official worship of the state. He speaks only to the human soul, to woo her, to “allure her… and lead her into the wilderness and speak tenderly to her,” and to convince her to give up her idols. No pagan god in any Classical myth ever spoke to humanity thus.

How we got there

Christendom was built not by the popes or emperors but on a prior foundation of the individual commitment of each Christian in the age of persecution amid a pagan society, the determination to turn away from the world and toward Christ at any cost.

The intense mystical love of the dedicated Christian for Christ is what made the terrors of the arena, wild beasts, grilles and all tortures, and all worldly temptations, as nothing. It was this high romance of the individual soul with the beloved that overcame and transformed the cruelties and barbarism of Classical paganism, not the Edict of Milan.

Anyone who wants to know how truly useless for building Christian civilisation it’s possible for the papacy to be - a corrupt episcopacy and papacy without this love of Christ - needs only to read the story of Marozia, the Theophylacti and the Pornocracy of the 10th century5.

Our institutions have collapsed: how to remake them

My friend the Prominent Monastic I mentioned above added the rather pertinent observation that if the classical monastic life refuses you entry, it “shows that it is not making itself available to souls who want to answer the universal invitation of Our Lord given to all to follow him in poverty, chastity and obedience.” It is, in other words, no longer fit for purpose, as the Brits say.

What is essential, he said, “is not the classical dream” of monasticism; habits, Chant and big buildings with pointed arches. What is essential is “seeking His face,” the “fuga mundi - fleeing the world - and saving souls, all the while surviving this desert world.”

In our time the Church’s leadership has effectively locked the gates of the monastic life6. “The hierarchy, ever seeking to control and domesticate whatever moves in the Church by their giving or refusing ‘official’ recognition, has all but left the Church without consecrated souls at all.”

My friend, however, moves past this saying simply that if we lament that there are no monasteries to join – none that would have us because of our refusal to give up certain aspects of the ancient Faith in favour of a supposed “New Paradigm” – we might not need them, strictly speaking. The life of devotion, of consecration to Christ, does not require marbled halls; it requires only the will to live it.

St. Anthony never sought a bishop’s permission or approval

“From the propositum we move to social structures. But the propositum is first.”

Following the example of the earliest recorded monastics, we remember that “the monastic life is adaptable, just like infants’ stem cells that adapt to all the needs of the body.” Where a young would-be saint of the 13th century had the luxury of simply joining the monastery down the road, a Christian of the 4th century had to be a pioneer. My friend said: “If in living the vows we flee the world, seek His face and seek to save souls by prayer or by labour, what more is needed to be truly a monk or a nun?”

Any person in any condition with the desire for sanctity “could be as good a monk or a nun as any who entered at 18 and made it to the golden jubilee! Because it is a matter of answering the universal call of Our Lord,” he said.

My friend continues with a DIY proposal: “In Egypt and Syria and everywhere else monasteries were nothing like the great Abbeys of Mont St. Michel, Kelso and Cluny. Our monastic stem-cell can build abbeys but just as well can find us a life like the eremitical lauras of St. Romuald or as itinerants like the Little Sisters of Jesus of Blessed Charles de Foucauld did in Chinese Junks and gypsy caravans.

“We’ve had 2000 years of all kinds of social structures to protect the propositum: look to the East and to the West. You name it we’ve had it. Caves; recluses; abbeys; priories; lauras; hermitages, huts, pillars, open-roofed enclosures. St. Simon Stock had an oak tree, Mother Potter had a hospice, and pious women lived together in houses in private vows or none. There has been no shortage of structures.”

“From the propositum we move to social structures. But the propositum is first. Then social structure. Any social structures that will protect and nurture the propositum, make it flower, is valid.”

And this means that in the absence of support from the hierarchy or existing structures we enjoy a divine freedom to re-create whatever old forms that will serve us now, in our rather straightened circumstances.

The propositum for all Christians

And this observation can easily be extended past the worries about vocational prospects for the religious life to the rest of the Church’s structures, locked in the deadly tar pit of the Modernist New Paradigm. The way forward for all of us is to make the interior “propositum” - to devote every aspect of our lives to the pursuit of union with God. And this is something that no one can stop us doing.

At its very core, with all external things stripped away, the life of the Christian, in any state of life, my friend said, “is a matter of making the propositum, making that act of holy resolve, of self-consecration of your life and entire being to Our Lord. Nobody can stop you. No order has control of it. No bishop. No Pope. Jesus gave every person the power and right to do it. It was the way of the early consecrated virgin martyrs, and they truly shine in every Canon of the Mass and are there remembered every day, hundreds of times a day all over the world.”

“If you have made a propositum all you need is a social structure to keep your consecration.” The requirement is only the consecration – the dedication of self, of family, of work, of prayer, of all of life’s goals, difficulties, struggles and sufferings.

And this is how Christendom was built: the radical choice of total dedication, consecration, to Christ for life, is the prior requirement for any hope of restoration.

The time of the desert has returned.

No need to go out to it anymore; the spiritual desert of Modernity has come to us. We have ground old Christendom to the dust. The physical structures - the buildings - might still stand for now but the social, cultural, spiritual structures that created them are already completely gone, razed to the ground by 250 years of rampant hatred for our Faith and the transformation of Christendom into a deadly ideological wasteland. If we are to start rebuilding, we have no choice now but to look to the earliest centuries and the Christians who started with nothing. Nothing but Christ who is all in all.

What did Christians do under pagan…and Arian and Nestorian…persecution? It’s true they hid in the catacombs, but perhaps more importantly to history, they went to the deserts either literally in space or interiorly at home. They gave their lives – and their deaths – completely to God. They devoted their every waking moment to Christ, to seeking His will and His Face, until it became a matter of indifference to them if they were persecuted, if they were arrested and tortured, if they lost their property or were exiled.

It was out of this voluntary embrace in the early centuries of spiritual poverty, indifference to the world and its fury, that Christendom grew to the extraordinary heights of the 12th and 13th centuries. When Christians had nothing, when there was no Christendom, no human law protecting them, no monasteries, no universities, nothing earthly to call their own, no glorious medieval past to look to, they turned to Christ Himself as all their wealth.

I’ve got a great story for you all: where did Sts. Benedict and Scolastica learn the monastic trade? They didn’t make it up themselves.

In fact, the young Benedict of Nursia arrived in Rome for his studies at exactly the moment a papal schism broke out between two rival political factions. It seems reasonable to think this worldliness was part of what prompted his fleeing the world to live as a hermit in a cave.

In Western theology the same idea is sometimes called “divinisation” or the “transforming union”. But since the decline of monasticism as the centre of Christian life and the Church’s reaction against the Protestant heresies, this idea has been first relegated to a secondary position after personal doctrinal orthodoxy and then finally almost forgotten altogether except in the few surviving monasteries that still pursue the ancient spiritual traditions.

It was a process:

312: Battle of the Milvian Bridge - Constantine defeats Maxentius.

313: He issues the Edict of Milan, which legalizes Christianity throughout the Roman Empire.

324: Constantine becomes sole emperor of the Roman Empire.

325: Council of Nicaea - adoption of Nicene Creed, condemnation of Arianism.

380: Emperor Theodosius I issues the Edict of Thessalonica making Christianity the state religion of the Empire.

Or pay close attention to the current news.

There’s a lot going on right now, with Rome working hard to suppress whatever is left, but the destruction of monastic life is a major feature of the post-Trent period. Secular governments started suppressing monasteries across Europe between the 16th and the end of the 19th centuries and the Church did little to protest or compensate.

Apropos of this, Lewis wrote in one of his letters once, “I sometimes have the feeling that the big mass-conversions of the Dark Ages, often carried out by force, were all a false dawn and the whole work has to be done over again."

I once spoke with a woman who had been part of a Benedictine option community gone awry. She spoke about how this sort of rejection of modernity is ultimately still a post-modern approach to the world. Ie. you get to choose the story you live in.

I’m just a dumb working class guy so take it with a grain of salt when I say that it seems to me that the crucifixion suggests we do not turn away from the world but face it and bear its suffering. That seems to have been Christ’s answer to Pilate’s “what is truth?”

Modernity is the desert. This is one of those ideas that is so obvious once someone says it.