What Is Heaven Actually Like? Visions, Symbols, and Joys of the Divine

Mere philosophy isn't good enough for heaven

In this fountain of sweetness, my soul was refreshed, as though it were a weary traveller who had arrived at his journey’s end. There, I felt myself renewed, with my heart melted by the tenderness of divine charity.

St. Gertrude the Great of Helfta

Did anyone watch the odd little sit-com a few years ago called The Good Place? I just finished it, and it made me realize that the secular world has completely failed to grasp what heaven (and hell) really are. In the show, the characters go through all kinds of adventures to “fix” the afterlife - envisioned, as usual, as a kind of eternal bureaucracy1 - to make it more just. But even heaven itself turns out to be problematic: it’s a place where endless pleasure and comfort eventually leave everyone bored and listless.

But this is what secular modernity offers; it’s all it has for us. In the absence of sacred images, the imagination has nothing substantial to latch onto when thinking of heaven. We are left with only a negative, as if heaven were simply an “absence of suffering” rather than an active, radiant existence filled with worship, love, and intimate divine communion. The Church’s saints and mystics have written about the ecstasies of heaven, but without visual symbols to match, their words alone struggle to stir us in a way that captures our hearts. We’re left with an imbalance: a world overflowing with images that excite earthly desires, while the beauty of heaven - the greatest of all desires - goes nearly unseen, tucked away as something too “mysterious” to even try to depict.

In today’s post for all subscribers, I’d like to take a closer look at what heaven is actually like, or at least how it has been glimpsed through the eyes of Christian mystics, scripture, and sacred art. Far from a dull, limited material “garden of earthly delights,” heaven has been envisioned by saints and artists as a realm where love, joy, and beauty reach their fullest expression in the unending and immediate presence of God - the Beatific Vision. Drawing from the visions of the Prophet Isaiah, and the three great mystics from the medieval monastery of Helfta, and the symbolic language of scripture and art, we’ll see a vision of heaven that the world can’t grasp.

The Sacred Images Project is a reader-supported publication where we talk about Christian life, thought, history and culture through the lens of the first 1200 years of sacred art. It’s my full time job, but it’s still not bringing a full time income, so I can’t yet provide all the things I want to and am planning for. You can subscribe for free to get one and a half posts a week.

For $9/month you also get the second half of the weekly Goodie Bag post, plus a weekly paywalled in-depth article on this great sacred patrimony, plus our Benedictine Book Club in the Substack Chat. There are also occasional extras like downloadable exclusive high resolution printable images, ebooks, mini-courses, videos and eventually podcasts.

If you would prefer to set up a monthly recurring donation in an amount of your choice, or make a one-off contribution, you can do that at my studio blog. Of course, anyone setting up a monthly patronage for US $9/month or more will get a complimentary subscription to the paid section here.

This helps me a lot because the patronages through the studio blog are not subject to the 10% Substack fee:

This is the site where I post photos of my own work as it develops. I have a shop there where some of my drawings and paintings are available for sale as prints, as well as some other items.

I’m stocking the Christmas shop and am happy to have found this lovely little Northern Gothic painting the other day that is made into a metal Christmas tree ornament.

Browse the shop for more Christmas treasure here:

Heaven is not an endless vacation in Aruba

The only solution The Good Place - that represents modern, secular man - could come up with for the ultimate pointlessness of existence was a door that you walked through when, after thousands of years learning and doing all the things you didn’t have time for in life, there was just nothing left to do. You came at last to “a feeling of peace” and walked through and were dissolved into the “energy of the universe” … or something. Whatever. I wondered whether anyone ever asked to see the manager.

The problem was obvious: heaven in The Good Place is only about earthly, natural “happiness,” infinitely extended. It’s a heaven with no God, with no final, ultimate purpose, no ultimate fulfilment outside our personal, passing whims and preferences. In the end of the series, when the characters got to the “real good place,” it was kind of crap, to be honest. It was clear that the imaginations of the showrunners - stunted by modern secular philosophies - were just not equal to the task of presenting an eternal afterlife that was worth striving for. They were not equal to the task of explaining what human life was actually for.

This view of heaven feels ultimately bleak and pointless for good reason. It reflects a vision of life and the afterlife that is purely material, where heaven is simply an eternal vacation, a place to relax and enjoy pleasures and experiences without any deeper connection. It leaves the characters searching for some deeper meaning or purpose that never arrives.2

The reason for this emptiness is strikingly clear: without God, without a source of infinite love and joy outside ourselves, even heaven feels hollow. The show is probably one of the best examples of why secular (especially modern) philosophies aren’t going to help you get where you really want to be. The secular world’s failure to grasp heaven stems from the lack of a concept for this ultimate purpose and presence. A vision in which the divine - the ultimate good - is absent and all that’s left are temporary joys that, no matter how extended, can’t fulfil the soul.

Heaven, in a word, is the presence of God

“Since everything desires its own perfection, everything desires God as its end”

Summa Theologica I-II, Q. 1, Art. 8

St. Thomas Aquinas describes God as the ultimate goal, or summum bonum (the highest good), which is indispensable to human purpose and happiness. According to Thomas, God is not only the source of all goodness but also the final end, or telos, of all human beings.

God Himself - possessing Him forever - is the final goal. Every human longing and pursuit ultimately points toward God as the highest good; the only one who can fully satisfy the soul’s infinite desire for happiness is the infinite God.

Heaven is the ultimate state of beatitude where the soul rests in the “beatific vision,” the direct, unmediated sight of and union with God. This vision is what brings the soul perfect and eternal happiness because, in seeing God, it finally beholds all goodness, truth, and love.

But how can we see this?

Why we need mystics - their visions help us see

We are presented every day, all the time, with visual representations of all possible earthly, natural, and material treasures of this life for envy and coveting. Advertising and media surround us with images that promise happiness, wealth, success, and status, creating a powerful pull toward the tangible, the consumable, the immediate. But the Church still presents the glories of heaven almost exclusively in the abstract, as formulaic proposals to which we give “intellectual assent” - a cold cup of coffee indeed. Heaven is talked about in words but rarely depicted with the kind of depth that stirs the human heart to a longing and love for the things of God.

We have the doctrines, the intellectual formulas, but they’re working on an imaginatively impoverished people who live in a radically desacralised culture - so it’s hardly a wonder that most people just don’t think much about heaven, much less yearn for it.

Once, Christian artists laboured to make the invisible realities of heaven visible: they painted the saints, angels, the gold of the “uncreated” divine light, and the awe-inspiring City of God. They captured heavenly glory not through realism but in symbols, through gold leaf, intricate patterns, and forms that transcended the limitations of “artistic” whims. These sacred images gave believers something beautiful and divine to focus on, to aspire toward. But as Christian art leaned toward naturalism, religious imagery increasingly mirrored the world around us, leaving us with the final result of eternal boredom and ennui of The Good Place .

The heaven in the visions of authentic mystics, as represented in scripture, poetry and sacred art is a completely different kind of reality. Heaven, as described by mystics like the Prophets Daniel and Isaiah, and in the middle ages by St. Gertrude the Great, St. Mechthild of Magdeburg, and St. Mechthild of Hackeborn, is far, far different from an endless extension of earthly enjoyments.

These mystics experienced heaven as an intimate, vibrant reality where love, beauty, and peace flow unceasingly - fountains of water are a common motif - because they are grounded in the presence of God Himself as these great saints experienced Him in this life.

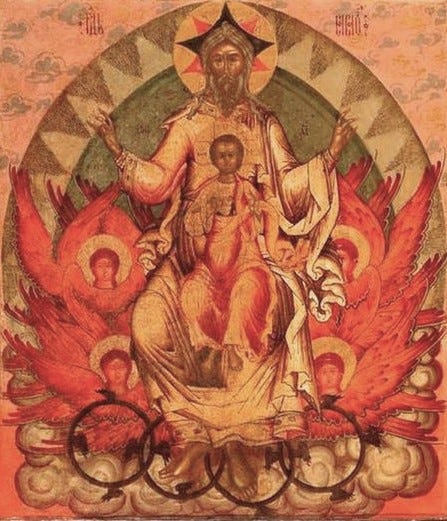

The Throne of Heaven - Isaiah

The prophet Isaiah’s vision of God in heaven is one of the most awe-inspiring and foundational passages in the Bible. His vision is described in Isaiah 6:1-4, where he sees the Lord seated upon a high and exalted throne, surrounded by seraphim - fiery angelic beings - who proclaim God’s holiness with voices so powerful they shake the very foundations of heaven:

In the year that King Uzziah died, I saw the Lord sitting upon a throne, high and lifted up; and the train of his robe filled the temple. Above him stood the seraphim. Each had six wings: with two he covered his face, and with two he covered his feet, and with two he flew. And one called to another and said: ‘Holy, holy, holy is the Lord of hosts; the whole earth is full of his glory!’ And the foundations of the thresholds shook at the voice of him who called, and the house was filled with smoke.

The images are symbols of God’s glory and utter holiness, His the sheer transcendence and power. Isaiah is overwhelmed by the sight, aware of his own unworthiness in the presence of such divine perfection, saying, “Woe is me, because I am pierced to the heart, for being a man and having unclean lips, I dwell in the midst of a people with unclean lips; for I saw the King, the Lord of hosts, with my eyes!”

The seraphim, covering their faces and feet, display reverence and humility, acknowledging that even they, as pure heavenly beings, are not worthy to gaze directly upon God’s glory. Their continuous cry of “Holy, holy, holy” underscores God’s otherness, His absolute purity and separation from all imperfection.

The imagery in this vision - the towering throne, the vastness of the Lord’s robe filling the temple, the smoke, and the trembling foundations - all communicate the overwhelming presence of God that fills not only heaven but all of creation with glory. This vision became a central influence on Christian and Jewish concepts of heaven and is often reflected in the liturgy of both East and West.

Confronted by God’s holiness, for Isaiah this encounter was transformative - as the Transforming Union is. He was struck by his own sinfulness but one of the seraphim flew to him with a live coal from the altar, touching his lips to purify him. The Angel said to him, “Behold, this has touched your lips. Your lawlessness is taken away, and your sin is cleansed.”3

This purification is a powerful image of God’s mercy, showing that even in His overwhelming holiness, God makes a way for the unworthy to be in His presence. Isaiah’s vision offers us a glimpse of heaven not only as a place of beauty and glory but as a realm where divine justice and mercy meet.

“In the land of heaven, everything is perfect. The air is alive with the beauty of flowing light, and all things bloom in radiant colours. Nothing fades, nothing withers, for all is kept alive by the endless fountain of divine love.”

Mechthild of Magdeburg

The Three Mystics of Helfta

St. Gertrude the Great (1256–1302): one of the most celebrated mystics of the Middle Ages, known for her intense and personal devotion to Christ. She entered the monastery at Helfta at a young age and became known for her visions, which focused on the Sacred Heart of Jesus, long before this devotion became widely recognized. Gertrude’s mystical experiences centred on the love of Christ as an overwhelming, heart-centred embrace, and she wrote extensively about the joy of being united with Him. Her writings, especially the Herald of Divine Love, are cherished for their deeply intimate descriptions of heavenly love and became influential in shaping Catholic devotion to the Sacred Heart.

Bl. Mechthild of Magdeburg (c. 1207–c. 1282/1294) was a Beguine and visionary mystic who joined the monastery at Helfta later in life, bringing with her a remarkable depth of spiritual insight. She is best known for her work, The Flowing Light of the Godhead, a poetic account of her mystical experiences. Mechthild’s visions described heaven as a realm of beauty and divine light, where God and the soul are united in a flowing dance of love. One included seeing rivers of golden light flowing through the heavenly realm, symbolizing the endless joy and love that emanate from God. Heaven, for Mechthild, was a paradise where each detail, the flowers, the colours, the light, reflected the divine love that sustains all creation.

Her writings reflect her unique, lyrical style and reveal a heaven filled with sensory delight and profound intimacy with God. Her work influenced both her contemporaries and later mystics, bringing a fresh, vivid language to the Christian imagination of heaven.

St. Mechthild of Hackeborn (1241–1298) the younger sister of Helfta’s abbess, was known for her gentleness and musical talents, as well as her devotion to the Sacred Heart of Jesus. She entered Helfta as a child and became a beloved teacher and spiritual leader.

In her Book of Special Grace, she had a vision of heaven as a place where God’s love was as gentle as a mother’s care, holding each soul in a close embrace. She saw herself resting against the heart of Christ, where she felt an unshakeable peace and contentment. In another vision, she was shown a paradise filled with angels and saints singing in perfect harmony, their voices rising like “a sweet fragrance” before the throne of God. For her, heaven was a realm of gentle joy and love, a place where the soul could finally rest, held securely in divine love.

The western iconographic prototype, the Coronation of the Virgin serves as an ideal symbol of heaven

One of the most beloved depictions of heaven in Western art is the Coronation of the Virgin, a scene where Christ or God the Father crowns the Virgin Mary as Queen of Heaven. This theme, popular from the medieval period through the Renaissance and Baroque, portrays heaven as a realm of divine majesty, unity, and celebration. Artists like Fra Angelico, Lorenzo Monaco and Gentile da Fabriano created versions of this scene, each emphasizing heaven’s beauty, joy and glory.

The Coronation of the Virgin serves as an ideal symbol of heaven for several reasons. First, it shows the heavenly hierarchy and order, with Christ, Mary, angels, and saints gathered in a harmonious, joyful and reverent royal court. This gathering reflects the vision of heaven as a place of ideal hierarchical structure and peace in which each person has a distinct, honoured place.

The Coronation prototype expresses the intimacy and love that defines heaven. Mary’s crowning represents the close, loving relationship between humanity and Christ. Viewers are invited to contemplate heaven as a place of ultimate joy, beauty, and love.

Heavenly Hierarchy and Order: The scene often includes a court of angels and saints surrounding Christ and Mary, symbolizing the harmonious structure of heaven. This ordered gathering reflects the medieval ideal of heaven as a place of divine hierarchy, where each person, from the angels to the saints, has a distinct and honoured place.

Divine Light and Radiance: Many depictions of the Coronation use golden backgrounds or radiating light or depictions of the stars of the cosmos around the figures to convey the unearthly beauty of heaven. This glowing effect helps viewers imagine heaven as a place filled with God’s eternal light, emphasizing that heaven is beyond earthly experience.

Intimacy and Love: The crowning of Mary signifies the close, loving relationship between humanity and the divine. Mary’s coronation by Christ or God the Father suggests a welcoming embrace into the heart of heaven itself, portraying heaven as a place of intimate communion and honour.

Mary as Queen of Heaven: The scene’s popularity is also linked to the devotion to Mary as Queen of Heaven and Intercessor. For believers, seeing Mary in heaven provides a comforting and approachable image of divine mercy and care.

It’s worth asking, how did modern people get the idea of the afterlife as a bureaucracy? Where did that ubiquitous trope come from?

I think the show was a project of people determined to make some practical use of their modern philosophy degrees, since it was mostly about Kant and a morality-free “ethics”. In the entire four seasons of the show Christianity and “religion” got a vague mention once each, and God not at all. Which, given it’s a show about making yourself worthy of heaven, seems like quite an accomplishment.

The Fathers of the Church always interpreted this as a symbol or type of the Holy Eucharist, and in the Eastern liturgy, after he receives Communion the priest recites the seraphim’s proclamation.

Thank you for this. Was having a very difficult day and feeling discouraged, just looking at beautiful art and remembering that our faith is in fact real and powerful…helped me pray our family rosary with something to meditate on and end the day on a hopeful note. Art is powerful.

I finished reading Dante’s Purgatorio a week ago. Towards the end of Purgatorio, Virgil leaves Dante and Dante is overcome by sorrow. But he realizes that Virgil (who represents human philosophy) cannot guide him any further into Paradiso. Until this point, Virgil had guided Dante through Inferno, all the way through Purgatorio till the earthly paradise (which is not the ultimate Paradiso). Dante is trying to tell us that human knowledge and philosophy get us only so far in the spiritual life. It doesn’t get us to heaven.