Sorry, Bin.

This is mostly going to be a re-post from my old Orwell’s Picnic blog. It comes to mind today because someone on Facebook inadvertently stepped on one of my personal landmines, making a comment along the lines of, “Hilary you’re oozing with talent,” and man did it ever rub my fur the wrong way. Because it always does.

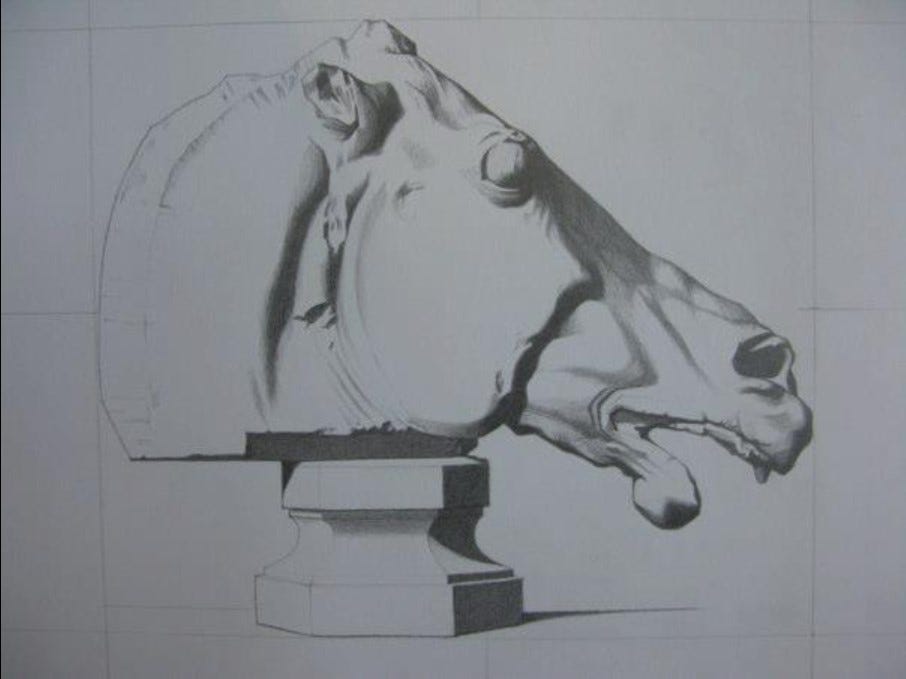

Poor guy. And he caught me at just the wrong moment and inadvertently touched a sore spot. I’d just spent about ten days struggling to push my drawing skills to their very outermost limits, forcing new neural pathways in my poor elderly brain, to try to bring my iconography work up to the next level.

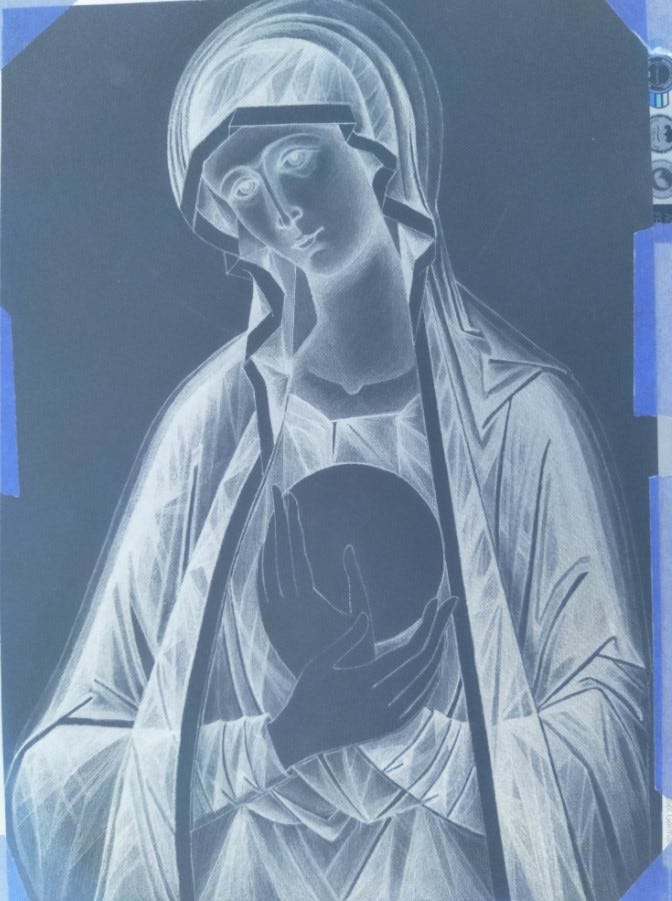

I finished this - a graphite preparatory drawing for the next commission of the Mother of God of Fatima - late last night. It was about the fourth 11-hour day of straight-up mental warfare, hunched over the worktable, brain, shoulders and back scrinched up tight.

As I explained here, the new technique requires that you draw it as if it is a photo-negative of the final piece. The darkest parts are the lightest parts. The original of this is graphite on white paper. And it was damn difficult. To understand it, you have to force your brain to reverse what you’re doing - which hurts. I think from now on, I’m going to do this with white chalk on dark paper, just to give my poor elderly brain-o a break.

And it worked. I’m sort of amazed at how well it turned out, because when I started this project I had no idea at all how the technique worked. I had to do quite a lot of looking-things-up and staring-at-photos and watching-of-videos - and several test drawings and small paintings - cramming a totally new, and not-at-all-intuitive technique into my brain by sheer brute force.

As a result of being basically mentally exhausted today (I’m taking a day off, and will get some housework done when I’m finished here) I came down on my admirer’s head, quite unfairly, like an Acme mail-order anvil out of a clear blue Arizona sky. He kind of went away mad, and justifiably. So, sorry about that, Bin.

I am also trying to learn a new Rule of Life: “Don’t be tetchy.” We’ll see how that goes.

But seriously, I mean it when I say there’s no such thing as “talent”

But the issue is a real one and I wanted to talk about it, because it is connected to a bunch of the things that should really be of concern to everyone. When we’re offering an easy compliment to someone’s work, if we stop and think for a moment about the implications, we could learn something useful and important. “You’re so talented,” is often accompanied by some variation on, “I couldn’t draw a straight line,” a phrase that irritates me so much I used to ban people from my commboxes who said it.

Why? Because of the built-in implications. First, that the person being complimented didn’t come from exactly the same starting point as everyone else - nothing, no skill at all. And, much more importantly, that he didn’t come to that ability through hundreds or even thousands of hours of gruelling, difficult, exhausting (and often expensive) training and work.

My instructor, the globally important painter and teacher Andrea J. Smith, said it’s common in all the drawing classes she’d ever taken or taught, for someone at some point to storm out in tears. She commonly likened doing a painstakingly detailed drawing as a battle. Maybe it’s different if you learn these basic skills as a child, when you’re supposed to, but for adults it’s emotionally and mentally very difficult to not be good at something, to have to fight with your own brain to learn something up to the point of mere competence. It’s a kind of warfare internally, and can be difficult for outsiders who’ve never done something like it to understand just how much struggle is involved. I was one of the ones who stormed out in a frustrated rage a couple of times. And I always went back.

But no one except your teacher and fellow students, and maybe some very close friends, could really understand this interior warfare. It’s understandable, I suppose, that someone who hasn’t done this would look at the end result, after years of this solitary struggle, and say, “Gosh, what talent!” They can’t know what was involved in getting there.

But in the larger implications it means that we’ve ditched things that were once common, skills that were taught normally to children, and now consider these abilities that used to be perfectly ordinary, to be some kind of magic. And that is something that worries me deeply, a sign of the broader and frightening cultural degeneration. There’s a bit of a meme running around the internet comparing the standard curriculum of a 5th grade classroom in 1900 to the 1st year university requirements today, and brother, it’s depressing. Drawing, being able to render a scene on paper with a pencil, was among a suite of competencies that were considered normal for all children before they ever set foot inside the school room.

It used to be taken for granted that school wasn’t the only place a child was taught things. The home wasn’t a place of constant relaxation, leisure and video games. The home was a place where the child was trained how to be an adult. A child was expected to make himself useful. To know how to use a knife and fork and sit at the dinner table without disturbing the adults by the time he was ten or twelve, how to sit respectfully through a church service, how to be a proper host when company visited. It was normal for him to have some musical training, some familiarity with domestic skills. He was expected to have accumulated a store of “general knowledge” from the books he read. In our time, it’s surprising and praiseworthy if he can read at all.

When someone looks at something an artist or musician and says, “You’re so talented,” the implication is that it’s something akin to a magic trick. Something so far outside the realm of ordinary people that there is no implied obligation - if it’s magic, no one but the magical could be expected to know it, leaving the speaker off the hook.

Anyway… here’s the post from 2013.

~

"I don't believe in talent. I recognise that there's genius out there; I respect it; I stand in awe of it. Most art has been produced by real people, everyday kinds of people, for whom art has become so important that they've developed the skills to say something that others have thought is very important also."

Myron Barnstone.

If you recall, we have officially banned the phrase "I can't draw a straight line" from the commboxes. It is meaningless drivel and is, as Myron Barnstone points out above, actually a kind of insult, both to the object of the speaker's putative admiration and to the speaker himself. It's actually a kind of dodge, that really means, "You must be some kind of freak to be able to do something that is so clearly impossible," and "I'm too lazy to be bothered to learn."

If "talent" is anything, it is love. It is the interest and drive necessary to keep you going for years of study and to keep you willing to sacrifice other things to get the skills to be able to proceed. I wish I had understood this when I was a child, or that someone had explained it to me. My grandma tried. She said to me once, in response to my complaints about the tediousness of some of the drawing exercises she tried to get me to do, "You haven't earned creativity yet."

It’s a trade

As Myron Barnstone says [in a video I can’t, in 2021, find online], for a Florentine boy of, say, 1430, apprenticed to one of the painters of the time,

"for 8 or 9 years he would be in constant training. And he would learn all of the skills, all of the craft, all of the techniques that everyone was being taught. And he would become the painter of Florence...Vasari would love to rewrite history and suggest that Raphael showed genius at a very very early age, as did Michelangelo and Leonardo...to what extent any of that's true we don't know. What we do know is when they started to get formal instruction, rigorous, demanding, disciplined, rote instruction, they responded favourably. And they developed rapidly. But all of the artists of that period came from the general population, and it was a working class background for the most part."

They were young people looking for a way to make a living.

"There wasn't any mystique and the words talent and genius was little heard. Today we only hear the terms 'talent' and 'genius' by someone who's offering training. I tend not to use the terms. Talent is the word that you find in the mouth of the lazy, the dismissive. All of the hard work that somebody else has invested after they've achieved something, their achievement is dismissed as being a product of talent. And that sort of implies that it didn't require anything on their part."

(Also, you have to learn the math)

“Talent” is only the willingness to do the work

"Talent," if there is such a thing, largely lies in application, the willingness to put the effort into learning the tasks and pushing through the obstacles and difficulties. This, I have said before, requires a kind of love. "Talent" therefore, is a kind of love, a love of the chosen art form, strong enough to make it a priority. Strong enough to make one willing to sacrifice other pleasures to pursue it.

I don't know about other types of arts, but about drawing - and we can probably assume the same applies to painting - I have learned through experience that it is a skill. Difficult to learn and requiring time and discipline, and instruction, but a skill like driving or cooking.

When I was younger, I assumed what everyone does, that "artists" have a "talent" they were just born with, like their eye colour. Or at most, they were born into a social atmosphere where art was encouraged - Yoyo Ma started his 'cello lessons when he was five, taught by his father. Cecilia Bartoli's first singing teacher was her mother - And if you weren't lucky enough to have been granted these advantages by the heavens you were sunk. Either way, you had to have this mysterious, innate thing, like the Harry Potter wizard gene, or you were simply doomed to a life of frustrated mediocrity.

Some of that, I have discovered, is true. There are certainly advantages that some people are born with and others miss. Some people are born into families where art and literature and good music are the norm and they are encouraged and guided to accomplish what they aim for. And there are good and bad places and times to be born. I can't imagine getting anywhere with artistic work without a reasonably leisured and orderly society to live in, one in which the struggle for bare survival is no longer the only concern. In times of stress or social upheaval or want or scarcity, not a lot of art, or work of any kind, gets done. Hunter-gatherers of the ice age did little art, as do North Koreans or Somalis of our time.

(But the fact that there is music and art from every human culture and every human epoch - no matter how brutal - has to indicate that "talent" is born into us as a species, not as individuals. It is human to want to create beautiful and meaningful things. Divine, perhaps. And surely it is therefore satanic to want to tear down.)

There is obviously also such a thing as genius1. It seems indisputable that a Leonardo or a Mozart, or for that matter a Newton or Kepler, were uniquely gifted men. They had all the necessary social support to do what they did. But I think we Modernians have a lazy habit of assuming that one has to be as freakishly gifted as that in order to qualify for this "talented" label. But we have to remember that such genius stands out because of its rarity, perhaps more even than its accomplishments.

But take the case of probably the most famous of these freakish geniuses: Leonardo. He was born the illegitimate son of a notary. He could not, therefore attend university and get the classical education that was the foundation at that time for all intellectual work. In his studies of nature he was self-taught, and lamented all his life that he never was able to formally study mathematics. He was apprenticed to Verrocchio at 15. At the time, this arrangement made for him by his father, was no more glamorous than learning to be a plumber.

Painting was a trade, with specific tools and (jealously guarded) techniques that one simply learned. A working class boy was given into this work in exactly the same way he might be to any trade and for the same reason: to earn an honest living. Painting was, and remains to the honest and non-puffed-up, work. A job. It is certainly possible to waste the training on someone who has no depth of perception, no strength of personality or character. No ideas. But I don't think those things, philosophical depth or perception or character, are what we call "talent" either.

We categorically reject the 19th century Romantic notion of the “Artist”

We can thank the self-absorbed and morally rotten group of people the 19th century came to call "The Romantics" for the silly notion that painting was some kind of divine calling. It was with the advent of this group of shysters, peddling the same kind of proto-New Age pseudo mysticism that we later got from the hippies, that we have our ideas about "talent".

And it was from them, ultimately, that we have the collapse of the Western art tradition. Once it all became about natural, inborn "talent," "creativity" and "expression" and no longer about hard work and diligent application to real techniques, it was no longer important that a young person learn to draw, or learn anything about the mathematics of composition, proportion or perspective. All that just seemed like too much work when you could just dip a basketball in some paint and dribble your way to fame and fortune.

~~~~~~~~~~~~

Thanks for reading

I could really use some help. Painting commissions and donations from my writing are for now my only source of income. If you would like to be a patron of the arts, or just a pal, you can donate through my Ko-fi support page here. (And don’t forget to click “follow” to get posts about my art work efforts.) Or you can donate directly, or set up a recurring donation, through PayPalMe, here.

Don’t forget that the subscriptions to this site are all free for now, so share it around if you know someone who might enjoy them. If you join, you’ll get each post directly to your email, so you don’t even have to click anything. And drop us a comment, join the conversation.

Also worth keeping in mind: Leonardo was called a genius in his lifetime. But he was also notorious for not doing the work, esp. paintings. He was constantly in conflict with his commissioners for starting things but never finishing them, despite having taken the cash (and spent it.) Don’t be like him.

Just a thought : the "talents" of the Gospel can be considered (although this is not the only aspect) as natural aptitudes – being more gifted for this or that. Just looking at my children I have seen since they were born that they have different "talents" – God certainly did not make us equal, and thanks to that there can be harmony. But we are ordered to make talents multiply – by all it takes; blood and tears and toil and sweat!

I think you're mostly right... there are three things, though, that make up "talent" in my mind:

- people who are quick learners at a skill. The skill doesn't come effortlessly, but some people learn certain skills faster.

- love, as you put it -- the desire to be good at the thing that makes you beat your head against the wall and throw countless thousands of hours at it.

- what you call genius - upper bounds to the skill. Almost everyone can learn almost every skill to a high degree of competency, enough to take on that profession. But the truly great people in a craft are built differently, whether physical or mental. They still won't get there if they don't put in the work.

For my chosen profession, software development, I have the first two - quick learning and love - but not the genius. There are only so many John Carmacks or Linus Torvalds or Dennis Ritchies of the world, and they truly are geniuses. But they also put in the work. The best part of my learning was whenever a layer of "magic" was stripped away, and I could see the "oh, OK, this is just something built by ordinary people who understood things deeply and applied hard-learned skills".

I am a terrible artist, but every time I actually put some effort into learning something -- building things with bezier curves, 3D modeling, etc. I pierce through the veil just enough to understand "oh, if I put 5000 hours into this, I could become good at this type of art." I think the same with drawing or music. But there's only so many hours in the day.

It actually drives me crazy working with various people who treat programming as this raw magical force that only special wizards that were born with it can wield, and the rest of people are just hapless muggles who were born without access to this mystic energy. Hogwash! Anyone that can learn 6th grade math can learn how to program. You just have to care enough to put in the time, and most people don't care enough. And that's fine!