I love animals. Always have. I get an overwhelming feeling of calm, delight and happiness - sweet joy - and often wonder and awe, when I see and interact with them. Having lived in cities most of my life, encounters with wild animals have been rare, and are all memorable. I grew up with cats and when I was small the neighbour’s horse lived in our back garden and I spent my toddlerhood and early childhood stuffing grass, carrots and apples into it, apparently unconcerned with our enormous difference in comparative size. To this day I can’t see a dog on a bus or in the piazza without feeling the urge to go pet it.

I remember the family of raccoons that lived in the woods beside my grandparents’ house, and my excitement and wonder when they came at night to eat the milk-soaked bread we left out for them. They seemed like quasi-magical creatures visiting from another, more wonderful world. For me as a child, animals and plants and the sea - the whole natural world with all its intricate mysteries - were representative of a kind of mystical reality, another world that I loved without having seen and longed to get to.

Animals, symbols, stories and meaning

Human interaction with animals is one of the most fundamental subjects in all our art, including all our legends and myths; from Paleolithic cave paintings and petroglyphs to 16th century Spanish Mannerism. Human life has flourished on earth over the millennia particularly because of our ability to create relationships with animals, not merely as prey, but for livestock and work, for protection and help in hunting, keeping vermin under control on our farms and dangerous predators at bay.

And those relationships are certainly still flourishing in the age of the microchip. It is fair to say that it is built into our “base programming” - our human nature - that we still have the urge to keep animals as pets and for work and personal assistance.

And in every culture, animals play a significant role in the stories we keep to define our cultural identity. In those stories, we have pretty well-established ideas about what different animals represent or mean. This is one of the fundamental, universal human norms: that we have the concept of symbols, and in every culture animals have symbolic significance; they mean things, because of our experience with them.

Icons or images of animals have cultural meaning beyond mere representations of the creatures themselves. The thing itself doesn’t have a meaning. A horse - the actual animal in front of you, just means a horse. A stag, when you spot one in the woods, means a stag. But when we humans create an image of a horse or a stag, and with that image tell a story about it, then meaning comes along. Meaning is what we add to the thing itself, by sending it through the processing of human mind, soul, history and culture.

.

Why is the Child Jesus holding a goldfinch?

The infant Christ and His cousin John the Baptist are playing with a cardellino - a goldfinch - as a prefigurement of the Passion and martyrdom they would both later undergo, and all that it brought about. The goldfinch is a very old medieval symbol of the Passion of Christ, and the salvation He wrought thereby.

We look at this painting and are intended to think about what is coming for these two innocents, what happened to them and why and what it all accomplished. You see the image and you know the message because you know the story. Woe to us when we forget.

To medieval people, these associations created the idea of the goldfinch, and the robin, who was similarly endowed with meaning, as having a relationship with all the power of the goodness of Christ. Because of that relationship it was believed to have the power of healing illness and blindness sight.

.

A thing that has meaning

A symbol is an object, character, figure, or colour used to represent abstract ideas or concepts - a picture that represents an idea that by itself can have no physical representation - salvation, redemption, hope. In Christian iconography a bird such as the sparrow, swallow, dove or finch, is always present as a symbol, an image or representation with sacred significance. In other words, it’s not just a sweet play on the emotions, a representation of the innocence of childhood for instance to make us smile, to depict the Christ Child playing with His pet goldfinch. It’s a prefiguration, a hint of things that are ordained to be, a set of symbolic messages which form a vocabulary we can learn to read.

The association of a goldfinch (European, that is) comes from its bright red cheek patches, and streaks of bright gold plumage. These are symbolic colours in Christian art and in the Christian mind - one for the Passion and the other for the ultimate goal - the glittering, untarnishing and everlasting perfections of heavenly bliss.

In a Byzantine icon or medieval or Renaissance painting of the Madonna and Child, angels, saints or of the Coronation of the Virgin, a gold background is often used to symbolise heavenly reality, bliss and unending perfection. Gold does not tarnish or lose its lustre, it does not corrode. All this shows that gold itself, the physical material, when it is applied to sacred art, means heavenly perfections, the perfect, never-cloying bliss we hope for, because of its physical properties and beauty.

The association of a goldfinch with the Passion is obvious: the colour red has always meant human blood in art. There are numerous legends, but one told that a goldfinch had alighted on the crown of thorns while Christ was suffering on the cross, and plucked off one of its thorns. Drops of the sacred blood splashed on the bird’s cheeks, and ever thereafter…

It’s unlikely anyone believed that was literally the reason goldfinches have red faces; the medieval symbolic mind was not so materialistic, so flatly literal, as we are. It was enough that the bird meant this, in art and in life - like a secret message from God through His creation.

.

Creation imbued with meaning

Traditional Christian sacred art is about this symbolic meaning. Not only did medieval art imbue its figures with symbolism, this practice derived from and revealed the way of thinking of medieval people. They could not have conceived of a world in which physical things did not symbolically “point to” other intangible, higher things. The modern, secular and materialist notion of “art for art’s sake” would have been incomprehensible (and probably pointless and stupid) to them.

The red of a real life rose in your garden “stood for” the blood of Christ crucified and the blood of the martyrs - and therefore our own salvation from our sins. The red or purple robes of the Virgin in a painting represented - meant - her humanity and ultimately pointed to her role in the Incarnation of the Logos - Christ.

Medieval man didn’t need to “learn theology” from books as a study, something separate from his ordinary life. There was no such thing as “ordinary life” as we conceive it in our flat, materialistic modern minds. His world was imbued to the atoms with a spiritual reality higher than mere matter, and his art - which he always saw in its correct context - was an illustration of that higher reality. And that higher, intangible, invisible reality was inextricably interlinked with this one, just as the human body and soul were fused together to make one person.

.

Saints and their beasts

The lives of the saints, the stories and legends associated with these astonishing people, are also closely associated with animals, often in surprisingly practical ways. Their interactions with wild nature tells us much about what the natural world means in Christian thought, what it is intended for by God.

We know of the story of Jonah and the Whale, in whose belly the prophet was not only saved from drowning but convinced to carry out the work of God to call the Ninevites to repentance.

We remember that ravens were sent to bring food to the prophet Elijah. And we remember the dove and the raven released by Noah to find dry land.

Stories of more recent saints and their association with animals abound in the Christian tradition. St. Francis, of course, was especially known for his habit of preaching the love of Christ to birds, and for taming the dreaded wolf of Gubbio. It’s worth thinking about: what is the symbolic meaning of that miracle, given what wolves mean in Christian sacred tradition? Did it happen? I think it did. But as with Scripture, these stories are understood on many levels both literal and symbolic.

St. Cuthbert, the great English abbot of Lindisfarne, was known for his great penances, and after standing in the cold sea up to his neck all night, was comforted by some friendly otters who came to warm him up. In another story, Cuthbert was forced to rebuke a pair of ravens (which some say might have been cormorants) who had damaged the roof of one of the monastery’s buildings. He banished them from the island. But the repentant ravens returned and were forgiven after they brought with them enough pig fat to waterproof all the monks’ boots.

.

Fairy and folk tales

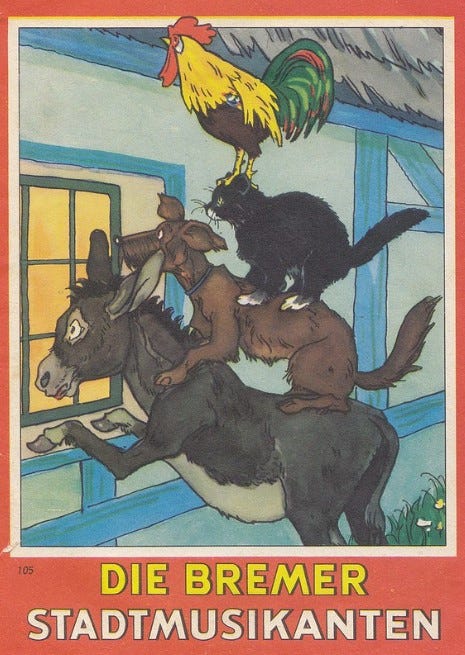

And outside the realm of Christian sacred art with its canons, we accept the notion of animals symbolising things without thinking. We have cultural ideas about the personalities and activities of cats and roosters, donkeys, foxes, wolves and stags and robins, bees and ants, from folk and fairy tales, fables and often the stories of saints and Christian legends.

And even now, in our late stages of cultural sterilisation, we’re familiar with the illustrations of these stories, and unconsciously absorb the meaning of animal symbols, from childhood. Across all human cultures, animals feature prominently in didactic moral stories for children, from Aesop’s Greece to India to Japan to Native American folk legends.

Owls are for wisdom because they were associated by the Greeks with the goddess Athena and by the Norsemen - those enterprising spreaders of culture and genetics - with the secrets of the underworld. Beavers, squirrels, bees and ants all mean industriousness and good old fashioned sensible countryman’s work ethic, getting on patiently with the real and tangible tasks at hand, preparing for the hard times that may come. When we say someone is “wolfish” we know that he is rapacious, greedy, unscrupulous and dangerous; a villain who will kill and eat your grandma. And you too, if you’re not careful, if you don’t match his wolfishness with your own cunning and courage.

All such imagery and mythology, of course, dates to well before the era of industrialisation and urbanisation, when most people don’t have to worry too much about getting eaten by wolves or losing a goose to a fox. Our artificial separation from the natural world has done more than anything else, I believe, to make us forget our stories, myths and symbols - our culture.

.

Sicut passer erepta est

One of the lines in the Psalms which we chant in the Divine Office that always catches and holds my attention is: “Anima nostra sicut passer erepta est de laqueo venantium…”

“Our soul is like the little bird that has escaped the snare of the fowler.”

It’s from Psalm 123:

Our soul hath passed through a torrent: perhaps our soul had passed through a water insupportable.

Blessed be the Lord, who hath not given us to be a prey to their teeth.

Our soul hath been delivered as a sparrow out of the snare of the fowlers. The snare is broken, and we are delivered.

It speaks of the troubles we have all had, the moral dangers imposed from without by others and those we allow to grow from within. And from these we are rescued, in an astonishing act, by the Passion of Christ. We are like helpless little birds caught in the net of a fowler - the devil - who wants to eat us. We cannot save ourselves, but we are released through a miracle, to escape.

And this is a message we have from God that we can still read; He cares for the smallest, most insignificant things. Swallows and sparrows and even flowers. Do you feel insignificant? Do you think your sufferings and difficulties are not seen or considered by God?

“Are not two sparrows sold for a penny? Yet not one of them will fall to the ground unperceived by your Father. And even the hairs of your head are all counted. So do not be afraid; you are of more value than many sparrows.”

~

I was in Ravenna for 2 days looking at mosaics in the Neonian baptistery, Basilica of San Vitale, Sant’ Apollinare Nuovo, mausoleum of Galla Placidia. I was stunned by numerous birds, animals, flowers, trees and plants depicted in the mosaics. Not only do they harken to a paradise lost, but they are symbols of purity, fidelity, etc. I’m in Perugia now and just visited the National Gallery which has an exhibit of Perugino’s works. I saw amazing tempera paintings on wood panels.

This is wonderful. I now have an extra reason to love the European goldfinch: which I have yet to see here in Portugal, though I know they are abundant! Can you recommend any books on Christian symbolism? I’m collecting ideas for an art project and am in the brainstorming/research phase! I’m looking at “Saints, Signs, and Symbols: The Symbolic Language of Christian Art” by Hilarie and James Cornwell. Thanks!