Friday Goodie Bag for June 28: What's an iconostasis?

Below the fold: A podcast on theology and sacred art, and a walk around an ancient Tuscan basilica or two

We’ve probably all seen an iconostasis in a Byzantine church, and though they are inevitably visually impressive, we might not have known much about its significance. Here’s a quick run-down, and we’ll finish with some pics from a series of recent articles from Orthodox Arts Journal.

Iconostasis: an architectural and liturgical element in Eastern Orthodox, Eastern Catholic, and other Eastern Rite churches, a screen or wall which serves as a stable support for icons and marks the boundary between the nave and the altar or sanctuary.

The iconostasis is not just a decorative element but a profound expression of theology and spirituality. It separates the nave from the sanctuary, creating a hierarchical separation between the earthly and the heavenly realms. The iconostasis serves as a visual and symbolic barrier, much like the veils and physical barriers in the Temple of the Old Testament, that emphasise the separation between the divine and the human, the sacred and the profane.

The use of a barrier to separate the altar area dates back to the early Christian church. Initially, this was a simple screen or curtain, called the templon. The icons displayed on the iconostasis provide a visual representation of the celestial church, an accurate depiction of cosmic reality, showing Christ, the Theotokos, angels and saints in a hierarchical ordering.

The icons in the church are intended to create a place that is at once in this world and in heaven. Churches in the eastern rites and Orthodox world are considered sacred spaces, even when they are not immediately in use, and are never used for any other purpose than the liturgical action.

Source: Orthodox Wiki

The layout of the icons of an iconostasis is imbued with theological meaning linked intimately with the meaning of the liturgical actions.

Not every iconostasis is exactly the same, but this is the general gist:

Theotokos with the Lord. This indicates the beginning of the end of time, the time of our salvation.

The Lord, Pantocrator, signifying the end of all time, the awesome day of judgment.

Saint John, the Prophet, Forerunner, and Baptizer of the Lord.

Patron of the church, or of its patronal feast.

The Holy Doors (or the Royal Doors). These usually are a diptych of the Annunciation or the four evangelists. This entrance is reserved for the use of the bishop, and the priest when he is carrying either the Gospel book or the chalice containing the holy Eucharist. In other words, it is reserved liturgically for the use of Christ as master and Lord.

North door will often depict an archangel, almost always St. Michael who guards the entrance to heaven.

South door is the liturgical entrance to the sanctuary, that represents heaven. On this door is Gabriel the Archangel, whose announcement to the Theotokos marks the beginning of the Incarnation, which is our entrance to the heavenly realm.

These icons (when present) are usually saints especially near to a parish or nation.

This is usually the icon of the Last Supper where the Lord instituted the Eucharist.

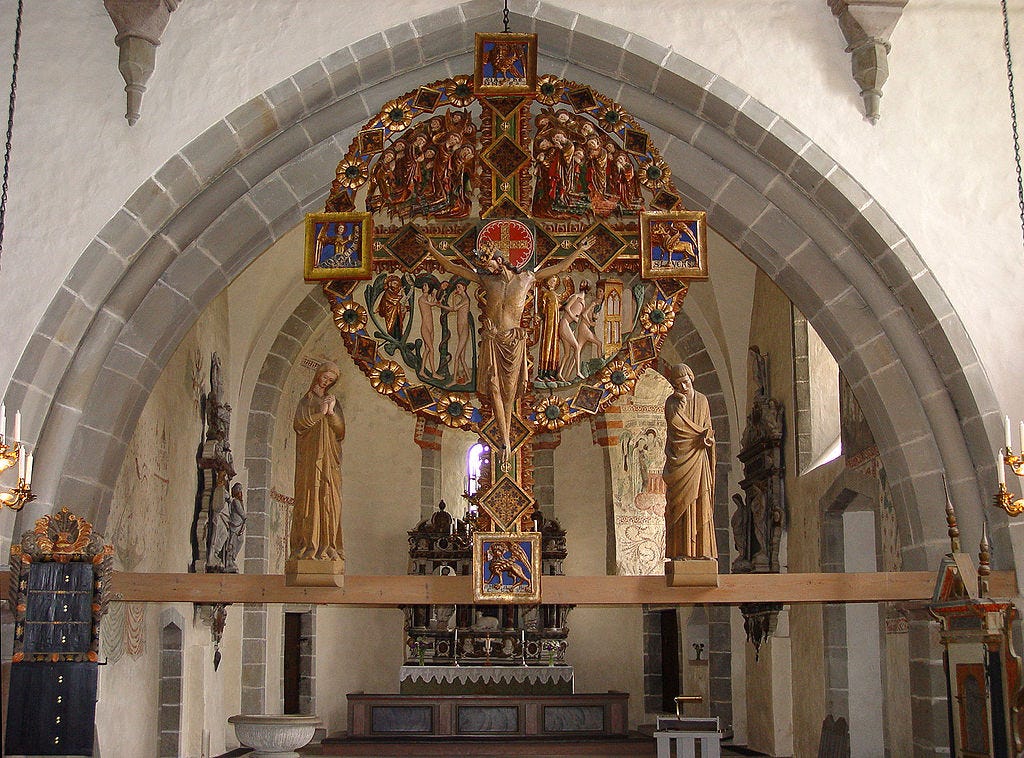

Rood screens

In late medieval western Christian churches we often had a similar structure that served a similar purpose1. They are often an open, lattice-like structure, allowing partial visibility of the altar and chancel, including the choir, while still providing a clear demarcation between the two spaces. Many included a rood loft or gallery above the screen, which could be used for reading scripture or singing.

Central to the rood screen is the "rood" itself, a large crucifix flanked by statues of the Virgin Mary and St. John the Evangelist - who are traditionally present on medieval depictions of the crucifixion, including our Umbrian panel crucifixes. The word rood is derived from the Saxon word rood or rode, for cross.

Both the iconostasis and the rood screen serve to demarcate the sacred space of the altar from the rest of the church. This separation emphasizes the sanctity of the altar area and the mystery of the liturgical rites performed there. Both structures are often richly decorated. The rood screen was often adorned with carvings, statues, and sometimes paintings. Both barriers symbolize the hierarchical nature of the church and the distinction between the clergy and laity.

The iconostasis is integral to the liturgical and theological life of Eastern Orthodox Christianity. The rood screen was prominent in medieval Western Europe during the Gothic period. It became less common after the Reformation when many were destroyed by Protestant iconoclasts, particularly in England.

Iconostases in Macedonia and Serbia

Just some photos lifted from a recent series of articles published by Orthodox Arts Journal. You can look at the whole collection here and here.

Bonus post: “Why can’t I pray?”

At least I know I’m not the only one.

Some good spiritual advice from Fr. Seraphim Aldea, the founder and superior of the Orthodox monastery of All Celtic Saints, Isle of Mull. I’m so glad Fr. Seraphim has taken up these spiritual talks again after his long hiatus. He talks like the monks I talk to in Norcia. If you want good spiritual direction; find a monk.

I hope if you’ve enjoyed the free material you’ve found here, and that if you think you might enjoy more in-depth and uplifting stuff, including the podcasts that are coming, you’ll consider taking out a paid subscription. Five months ago, I scrinched up my courage, closed my eyes and held my breath, and took the risk of diving head first and full time into this project and just hoped it would work. And I’m kind of amazed by what a good gamble that was. There’s lots of plans afoot going forward, and the only way to do any of it is with your support:

The Sacred Images Project is a reader-supported publication where we talk about Christian sacred art, the first 1200 years. It’s my full time job, but it’s still not bringing a full time income, so I can’t yet provide all the things I want to and am planning. You can subscribe for free to get one and a half posts a week.

For $9/month you get a weekly paywalled in-depth article on this great sacred patrimony, plus extras like downloadable exclusive images, ebooks, mini-courses, photos, videos and podcasts (in the works).

If you’d like to choose the amount you contribute, you can set up a monthly patronage at my studio blog, Hilary White; Sacred Art here:

Subscribe to join us!