Goodie Bag for Oct. 26th: A tour of a 13th c. manuscript, and some digital medieval downloads

Below the fold: A reflection from Mother Marie on how to keep going in the disasters and some top quality photos for nun-gazing

A Tour of the Rothschild Canticles

Today, we’re diving into a mystical treasure: the Rothschild Canticles, an intimate late 13th-century manuscript full of extraordinary and unusual illuminations. It’s one of those enigmatic medieval books that leans heavily into contemplative mysticism; not a bible or psalter but a compendium of commentary, poetry, songs and mystical treatises by the likes of Augustine. It’s equal parts art, mystery, and meditation aid.

Made around 1300 in northern France or Flanders, it is thought to have belonged to a wealthy, deeply devout woman who wanted a visual guide to her inner spiritual journey. It’s a blend of spiritual allegory, rich colour, and lavish detail, and loads of gold leaf, meant to transport its reader into a world of divine visions, personal transformation, and heavenly beauty.

Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library:

An intensely illustrated florilegium1 of meditations and prayers drawing from Song of Songs and Augustine’s De Trinitate, among other texts, the Rothschild Canticles is remarkable for its full-page miniatures, historiated initials, and drawings, which show the work of multiple artists. The text, apparently a unicum, is a cento of biblical, liturgical, and patristic citations, with some additional material spuriously attributed to St. Bernard. The most important sources are the Song of Songs, the other Wisdom books, the Prophets, and, in the Trinitarian section, Augustine’s De Trinitate.

A unicum in the context of medieval manuscripts is a one-of-a-kind manuscript that exists as the only known example of its type, text, or artwork. This term refers to manuscripts that have no other surviving copies, making them uniquely precious both in their content and physical existence.

In the world of medieval studies, unica are especially valuable to scholars, as they offer singular insights into the textual, artistic, and cultural practices of their period. Each unicum provides unique evidence of regional styles, local dialects, artistic influences, or specialized knowledge, making them indispensable to understanding medieval intellectual and artistic history.

One medieval scholar, Jeffrey F. Hamburger, wrote:

The images in this book are not allegories that need to be interpreted. The text gives not explanations of the illustrations. Instead they are representations of mystical vision. They are not simple representations for teaching the unlettered, but together with the text are meant to be aids to the reader's own spiritual progress toward mystical union.

Further reading

Last year we explored the medieval concept of the “hortus conclusus” - the “garden enclosed,” the symbol of the soul’s interior “tryst” with God.

The Gothic garden paradise

Despite the multiple woes of Europe between the 14th and mid-15th centuries - including the devastation of the Black Death (~1347-1352) - the period produced some of the most charming and cheerful sacred art of our history.

The Bride of Christ: Love Divine and the Tree of Life

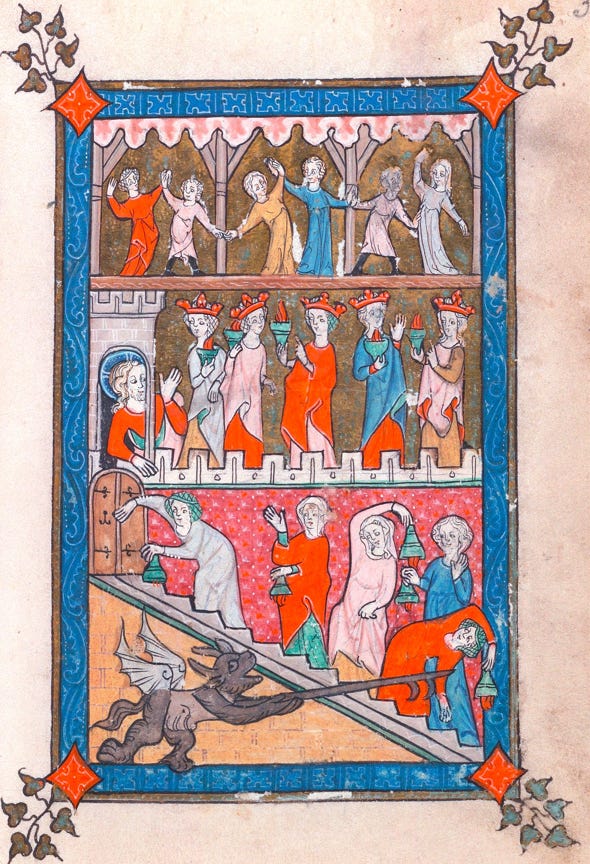

The imagery can be obscure to us, especially if we are not completely familiar with the texts being referenced, or with medieval symbolic mystical imagery in general, but we can have a go at “reading” some of them at least.

The Tree as the Cross: The cross is depicted as a living tree, a common medieval symbol linking the crucifixion to the idea of the “tree of life”. Christ’s crucified body is at the centre, because it is his sacrifice that brings eternal life. He is the “vine” and the “door”.

The Ladder of Divine Ascent: The figures climbing up the branches as though they are a ladder shows us the spiritual life as the “ladder of divine ascent.” This idea, rooted in the writings of the Desert Fathers, represents the soul’s journey toward God through virtue and discipline.

The Wise Virgins: They are positioned on the left side, each holding a small vessel or lamp with a flame, symbolising their spiritual readiness and the light of their faith. The wise virgins are actively participating in the ascent, showing their preparedness and ability to receive divine grace.

The Foolish Virgins: On the right side, we see figures who appear empty-handed or with downcast expressions. Their vessels are overturned, illustrating their unpreparedness. Their positions, expressions, and gestures reflect regret or a sense of exclusion from the ascent, emphasising the parable’s warning about being unprepared for Christ’s coming.

Christ and His Mother: The Child hands the Wise Virgin a wreath, symbolising eternal victory over sin and death, her consecration to him in a mystical marriage.

The Mouth of Hell as a Warning: On the right side of the tree at its base, we see the open, dark, monstrous mouth of a beast representing the mouth of hell. This visual juxtaposition reminds the viewer of the spiritual dangers of neglecting the interior life and the ultimate consequences of failing to live in readiness for divine judgment.

Visions of the Trinity: A Divine Dance

In medieval manuscripts in western Christianity, visually depicting the Holy Trinity presents a challenge, and it was often the subject of some imaginative - and decidedly “non-canonical” - images. The Rothschild Canticles presents the Trinity in ways that are both familiar and sometimes very strange.

Barbara Newman, a professor of Latin and Classics at Northwestern, called these images of the Trinity, “a playful, intimate approach to the triune God, marked by spontaneity rather than solemnity, dynamism rather than hieratic stasis, wit rather than awe.”

“There is no hint of narrative, but something more like an eternal dance. . . . The divine persons are caught up in an everlasting game of hide-and-seek with humans while they enact among themselves, in ever-changing ways, that mutual coinherence that the Greek fathers called perichoresis—literally ‘dancing around one another’.

A download

I thought this image from the Rothschild Canticles would make a nice digital pdf download. As always I’ve bumped up the brightness and colour saturation a little from the original download.

The Sacred Images Project is a reader-supported publication where we talk about Christian life, thought, history and culture through the lens of the first 1200 years of sacred art. It’s my full time job, but it’s still not bringing a full time income, so I can’t yet provide all the things I want to and am planning for. You can subscribe for free to get one and a half posts a week.

For $9/month you also get the second half of the weekly Friday Goodie Bag post, plus a weekly paywalled in-depth article on this great sacred patrimony. There are also occasional extras like downloadable exclusive high resolution printable images, ebooks, mini-courses, videos and eventually podcasts.

If you would prefer to set up a recurring donation in an amount of your choice, or make a one-off contribution, you can do that at my studio blog.

This helps me a lot because the patronages through the studio blog are not subject to the 10% Substack fee.

I’ve been restocking the online shop with some of the printed items for this year’s Sacred Images Project Christmas market. People tell me all the time - and I’ve found this myself - how difficult it can be to find really nice religious cards and decorations for Christmas. So I’m focusing this year on cards and tree ornaments that will bring some medieval imagery into your holidays.

Lots of other things are posted, and more to come…

Subscribe to join us in the paid section “below the fold” of today’s post, where we have a reflection from our friend and resident Benedictine superior, Mother Marie, on keeping going in the face of All This, as well as some lovely photos she’s sent me of the sisters living the life in the mountains of Liguria.

Holy Mother the Church, after her great humiliation and passion, will be able to lift up her eyes and see that despite the work of her enemies, there was another work going on in secret places, a work inspired by God. These will be all those children that persevered in the darkness, and continued to abide by the law of God and that did not participate in the destruction of the holy places.