Icons and the Shroud: Yes, we really do know what Christ looked like

Why our artistic tradition is trustworthy

You’ve probably seen those AI-generated “historically accurate” depictions of Jesus making the rounds online, claiming to be based on population averages or genetics or some other kind of speculative forensic reconstruction. “Scientists have uncovered the real face of Jesus!” the headline from the venerable scientific journal Popular Mechanics blasts.

And funnily enough, every one of these “discoveries” is presented either by the claimants or the media as challenging the traditional depictions we see in churches, icons, and sacred art.

These images are then brandished as a weapon on social media - often around Easter - against the gullible Christian fools who think their ancient artistic tradition is trustworthy.

In today’s post for all subscribers, we’re going to take a close look at how that traditional image of Christ suddenly appeared about the middle of the 6th century in the ancient Near East, and why it is a good deal more trustworthy than the latest speculative anti-Christian fictions.

A quick note for print customers - how to get a nice finish on your wood panel prints

I made this little follow-up video showing the results of my refinishing of the Virgin of the Embroidered Foliage wood panel print. I’m very pleased with the outcome. If you’ve bought one, you can follow the same procedure very easily. I give the basic instructions here, with a video

I got one of these prints for myself and am quite pleased with the quality and accuracy of the colours, but I found the plain finish of the wood wasn’t as nice as it could have been. So I’ve been suggesting to customers that they give it a few coats of natural shellac varnish, and a final finish of Windsor and Newton satin spray varnish, all of which you can buy at any online or real life art supplier.

You can order a print and lots of other nice things at the shop, like Christmas cards with some of the sacred images we’ve looked at, notebooks, tree ornaments and prints on paper and wood.

I’ve been restocking the online shop with some of the printed items for this year’s Sacred Images Project Christmas market. Like this little Sienese Gothic angel tree ornament:

People tell me all the time - and I’ve found this myself - how difficult it can be to find really nice religious cards and decorations for Christmas.

Enjoy a browse:

At the Sacred Images Project we talk about Christian life, thought, history and culture through the lens of the first 1200 years of sacred art. The publication is supported by subscriptions, so apart from plugging my shop, there is no advertising or annoying pop-ups. It’s my full time job, but it’s still not bringing a full time income, so I can’t yet provide all the things I want to and am planning for.

You can subscribe for free to get one and a half posts a week.

For $9/month you also get the second half of the weekly Friday Goodie Bag post, plus a weekly paywalled in-depth article on our great sacred patrimony. There are also occasional extras like downloadable exclusive high resolution printable images, ebooks, mini-courses, videos and eventually podcasts.

If you would prefer to set up a recurring donation in an amount of your choice, or make a one-off contribution, you can do that at my studio blog.

This helps me a lot because the patronages through the studio blog are not subject to the 10% Substack fee.

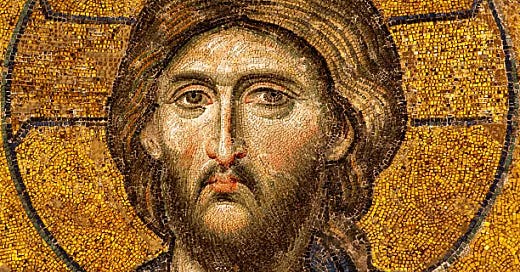

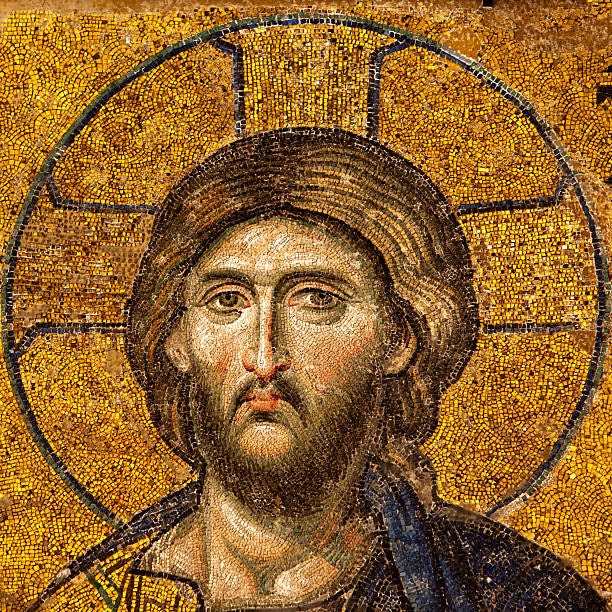

We are regularly called gullible by those enamoured of modern secularism’s chronic historical scepticism, but here’s the surprising truth: the Christian tradition of Christ’s appearance, particularly in Byzantine and later western medieval art that followed its canons1, has a strong basis in history, and not just theological imagination. Far from being a mere artistic interpretation, Byzantine representations of Christ align remarkably with the facial features imprinted on the Shroud of Turin.

Recent scientific findings reinforce that the Shroud is not a painting or an image created by any method known either now or in the middle ages, but bears a photograph-like likeness of a particular person. In this light, the sacred art tradition isn’t just trustworthy, it might be one of the most enduring witnesses to the physical reality of Christ as both man and God.

The tradition changed abruptly

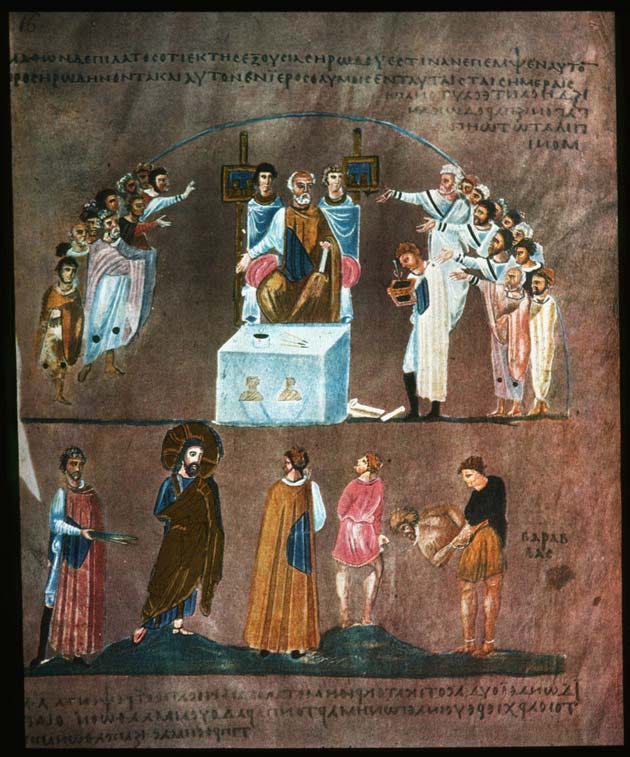

In an ancient church in Thessaloniki, there is a most intriguing work of mosaic art dating to the 5th century. Christ is pictured as a beardless youth sitting on a rainbow, His left hand up in salute while His other rests on the rainbow, holding a scroll. This mosaic is uniquely important, not only because it is only one of only three intact dating from that period, but because the mosaic is enigmatic in its symbolism. From the conventions of Byzantine figurative art we know now, this youthful Christ is hard to recognize at first.

Why? Because the figure lacks a beard.

One might not think that this feature is so very significant, but it is certainly possible to use it to track a very abrupt and distinctive change in depictions of Christ from the middle of the 5th century to the middle of the 6th. Before this, Christ was often depicted in a variety of symbolic ways: as a youthful shepherd, a Roman senatorial orator or priest, and - following the conventions of Roman art in which high ranking Romans and respectable men were clean shaven - without a beard.

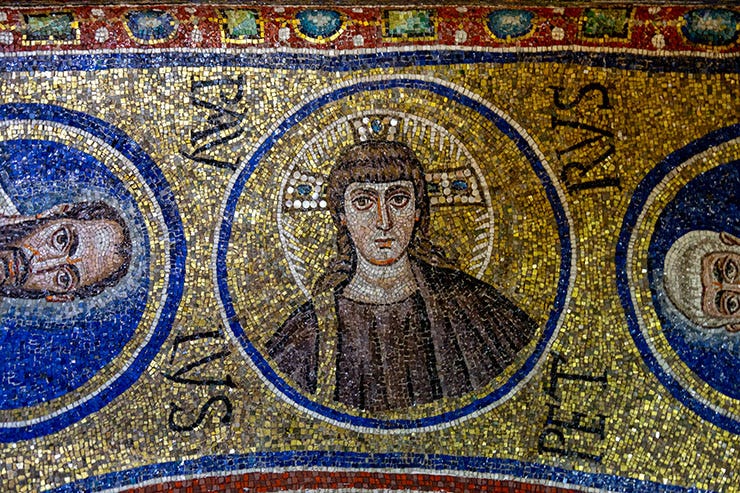

However, starting in the 6th century, a striking consistency emerges in Christian art. Christ from this time onward is almost universally portrayed with an elongated face and nose, with sharp cheekbones, a divided beard and long hair falling to His shoulders. These features are unmistakably consistent with the image on the Shroud of Turin.

How long ago did Christians know about the Shroud?

In the Byzantine tradition, the Shroud was known in early Christianity, long before it appeared in France in the 14th century, and is believed to have been kept in Edessa (modern-day Şanlıurfa, Turkey) before eventually making its way to Constantinople. During the Fourth Crusade (1204), Constantinople was sacked, and many sacred relics were destroyed or looted and dispersed.

In the western Church, the Shroud’s first confirmed historical appearance was in the 1350s, when it was displayed in Lirey, France, by the de Charny family. Geoffroi de Charny, a French knight, is believed to have obtained the Shroud, though how he acquired it remains a mystery. It is recorded that Geoffroi participated in several crusading campaigns, including the Battle of Smyrna (1344) during the Crusade of Smyrna, which targeted Muslim-held territories in Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey).

De Charny, as a crusader and a man of significant influence, could have acquired the Shroud either directly during his campaigns or through networks of relic traders and collectors who dealt in sacred artifacts from the Middle East. It’s worth noting that during this time, there was an active trade in relics, and many knights returning from the Crusades brought back religious artifacts to enrich churches in their homelands.

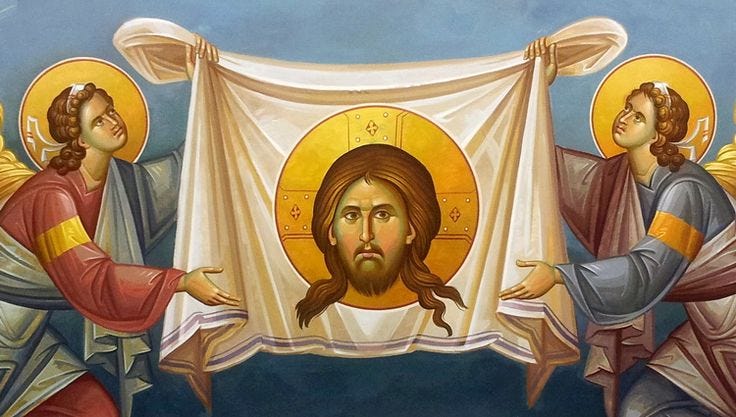

Mandylion; image not made by hands - lost and found

The Mandylion of Edessa was a miraculous image of Christ, described as “not made by human hands”. It was said to have been given by Jesus Himself to King Abgar V of Edessa. In a story recorded in the 4th century by Eusebius of Caesarea, King Abgar, who suffering from an illness, sent a messenger to Jesus in the last year of Christ’s ministry, asking for healing. Jesus responded that He could not come himself, but sent a cloth to which He had pressed His face, leaving the image imprinted on it, by the apostle Thaddeus.

The cloth cured the king and Christianity was brought to the region2. The Mandylion was kept at Edessa and venerated by the whole community with regular processions.

One tradition holds that in the 3rd or 4th century, when Edessa and its Christian community faced waves of persecution, political instability and threats from invading forces, the Mandylion disappeared. Some say it was hidden to protect it from destruction or theft.

In 544, a catastrophic flood struck Edessa, damaging large parts of the city, including its walls. As workers scrambled to repair the city’s defences, they uncovered a hidden niche in the wall above one of the city gates. Inside this niche was none other than the Mandylion, miraculously preserved.

The rediscovery was seen as a sign of divine intervention, and the Mandylion quickly regained its status as the city’s most prized relic. It was paraded through the streets, credited with saving Edessa from the flood and later with repelling attacks from invading armies. The Mandylion became a symbol of Christ’s protection over the city.

It was after this, the mid 6th century, that the abrupt shift in depictions of Christ we discussed above began.

To Constantinople - the Shroud and the Mandylion

In 944, the Byzantine Emperor Romanos I Lekapenos heard of the Mandylion’s miraculous powers and struck a deal to bring it to Constantinople. After negotiations, the relic was transferred to the Byzantine capital with great ceremony. It was enshrined in the Church of the Virgin of the Pharos, where it became one of the empire’s most revered sacred objects.

Some historians and researchers posit that the Mandylion - which was reported to be a small square piece of cloth - and the Shroud of Turin are the same object, proposing that the Shroud was displayed folded in such a way that only the face of Christ was visible. Some believe that during the Fourth Crusade in 1204, the Mandylion, or the Shroud or both, were looted from Constantinople and somehow the Shroud that we know today eventually made its way to France.

One thought occurs that might suggest that this folding theory has some truth in it: the Shroud itself, as we know it today, the full length, double-sided, photo-negative image of the full body of a man horrifically brutalised to death, has never been used in the iconographic tradition in any age as a prototype - there are no icons at all nor even paintings of the object itself until every late. In fact, we saw it depicted for the first time only in the 14th century in the form of the Lirey pilgrim’s medallion from France.

On the other hand, if the Shroud had been completely displayed as such in either Edessa or Constantinople, we would have had some visual record at least, as we do with the Mandylion; if not a whole genre of Christian art based on its full length image dating far before the Lirey Medallion.

But how?

Whether there were two miraculous cloth images or only one, both are revered as acheiropoietos, images “not made by human hands,” but by the miraculous intervention of God.

The Shroud has long been associated with healing miracles, particularly during the medieval period when it was displayed for public veneration. Pilgrims who came into contact with the Shroud or prayed before it reported miraculous recoveries from illness or injury. While such claims are difficult to verify after centuries, the one question of the Shroud’s origin or making remains unanswered by “modern science,” though efforts to “debunk” or discredit it have continued.

Most recently Cicero Moraes3, an expert in forensic facial reconstruction and software developer, has claimed that if the Shroud had enveloped a human body, receiving the image from fluids on the body, it would have produced a distorted image, and not the “photocopy” type image we see.

From this, Moraes suggests that the image we do see on the Shroud is a work of Christian art. He said the image could have been created if a cloth was placed over a bas-relief of a human figure, such as a shallow stone carving.

“It seems to me more like a non-verbal iconographic work that has very successfully served the purpose of the religious message contained within,” he said. He offers no theory of how such a work of iconography could have been achieved as we see it today on a piece of cloth, that has been shown to be 2000 years old and originating from the Middle East, nor how such an image made from draping over a bas relief carving would have had both back and frontal views.

He also seems to simply not have heard of some of the Shroud image’s other oddities, like the fact that a whole, uninterrupted image is visible, but it has been shown there were parts of the body the cloth did not touch. The image also appears only on the first few micro-fibres of the linen, but go no deeper into the cloth.

The “artist” hypothesis - a painterly eye-roll

I’ve personally always been impatient with the suggestion that it is a “work of Christian art”. Quite apart from the total absence of pigments or dyes, no one in the middle ages would have even conceptualised a photo-negative, let alone had the slightest inkling how light could be used to create such an image. This suggestion is even more absurd now that we know the cloth does in fact date to the 1st century AD.

Mr. Moraes suggests that it was created for iconographic - that is - devotional reasons by a Christian artist. But what on earth would a Christian artist of the 1st or 13th century have thought to achieve by creating a photo-negative, even if he had been, by some freak flash of genius, able to conceive of such a thing?

The purpose of iconography was and is to excite devotion in the viewer by visually representing theological realities. But this barely-there, ghostly negative could not possibly have succeeded in that way for a man of pre-modern visual mind. No one had any notions at all that images could be created in that way, so that assumption would certainly never be made by any viewer, nor would any artist imagine it would be. Before the early modern period, the common man simply would not have had the ability to mentally translate such a thing into the kind of visual understanding that icons are for.

Moreover, there are no other examples - not one - of what we now call “photo-realism” in medieval or Classical Roman art. The image, when it is enhanced and flipped into a photo-positive, is a photographic, not artistic image. Since photography did not exist and the photo-realist style was outside the possible mental framework of anyone alive, even very realistic drawing styles were at least somewhat stylised and “artistic” or painterly.

The Shroud - if it were the work of an artist - was painted in a style that no medieval mind could possibly have produced. And why would he have bothered? Artists who wanted to create devotional images of the crucified Christ simply did so, as we see with the uncountable multitudes of images of the Veil of Veronica and the Mandylion, etc.

Billions of watts

Mr. Moraes also seems unaware of the findings that the image on the cloth has not the slightest trace of anything like pigment, dye or paint medium on its surface. We do, finally, know that the image was not produced by contact of the fibres with any kind of liquid, including blood or other body fluids. It is in fact a kind of scorch mark.

Experiments with excimer lasers have demonstrated that it’s possible the scorching was formed by some form of electromagnetic energy, emitted in a brief but fantastically powerful flash. In 2011, researchers at Italy’s National Agency for New Technologies, Energy and Sustainable Development (ENEA) conducted experiments exposing linen samples to UV lasers. The UV light caused chemical reactions in the cellulose of the linen, leading to discoloration without affecting deeper fibres.

However, the energy required to produce such an image would necessitate UV light sources far more powerful than any available during the medieval period, suggesting that the image’s formation involved phenomena beyond current scientific understanding - never mind the understanding of a Christian “artist” of 1st century Palestine.

Physicist Paolo Di Lazzaro demonstrated that UV photons could account for the thin coloration and unique appearance of the image, even in areas where the cloth didn’t touch the body. Their research indicated, however, that creating such an image would require billions of watts of light energy, far exceeding the capabilities of any known UV source today. And that energy would have had to be emitted no longer than a fraction of a second to produce the effect without burning the cloth.

What we know

In case anyone wants an itemised list for bringing out at dinner tonight, the Shroud has been studied far more extensively than any other Christian relic. Here is a brief list of some of the things science has ruled out and discovered:

No chemical cause: The image was not created by vapours from chemicals or the corpse itself.

Interior of the body: In addition to resembling an X-ray, the Shroud image highlights internal anatomical details such as bones in the hands and teeth in the skull. This feature is not easily explained by natural or artistic processes.

Presence of blood and serum: Chemical and forensic tests have confirmed the presence of real blood on the Shroud. UV fluorescence studies have also revealed serum stains around the blood marks, which would not appear in a painting or forgery.

Blood type AB: Studies have identified the blood type on the Shroud as AB, a finding that intriguingly aligns with analyses of blood from Eucharistic miracles, including Lanciano, Italy (8th century). The Sudarium of Oviedo, a bloodstained cloth said to have been placed over Christ’s face at burial, has bloodstains matching those on the Shroud of Turin. The stains aligned with the facial wounds depicted on the Shroud.

Absence of pigments or dyes: Microscopic and chemical analyses have confirmed that there are no pigments, dyes, or paints on the Shroud that could account for the image. This rules out traditional artistic methods.

Superficiality of the image: The image resides only on the outermost layer of the fibres (about 0.2 microns thick). The coloration does not penetrate deeper into the threads or the cloth, unlike stains or paints.

Three-dimensional information encoded in the image: The Shroud’s image contains unique three-dimensional information that can be analysed using digital mapping. This characteristic was discovered during NASA's work with the VP-8 Image Analyzer, which revealed that the image brightness corresponds to the body-to-cloth distance, unlike ordinary photographs or paintings.

Lack of directionality: Unlike brushstrokes or mechanical application, the image has no directionality (e.g., no brush or tool marks), indicating that it was not manually created.

Presence of pollen from the Middle East: Studies by botanist Max Frei and others identified pollen grains from plants native to the Middle East, particularly around Jerusalem, on the Shroud.

Dust and soil particles: Microscopic analysis has identified particles of dust and soil on the Shroud, including material matching limestone from the Jerusalem area, further supporting its historical claims.

Details of the crucifixion wounds: The image shows anatomically accurate details of wounds consistent with crucifixion, including:

Nail wounds in the wrists rather than the palms (contrary to medieval artistic conventions).

Blood flows consistent with gravity and the positioning of a crucified person.

A wound in the side, consistent with a lance piercing, as described in the Gospels.

Edessa became a major centre of Christianity, and was home to the School of Edessa, a centre of Syrian theological scholarship.

Many thanks to Alert Reader, Fr. Brian Harrison for bringing this to my attention.

Thanks for this post, Hilary. I've read so many books about the shroud over the last 20 years, and you've managed to summarize the most important findings in this post. The shroud also seems to be Our Lord's proof of the resurrection. That same force that seared the image of His sacred body onto the linen probably also blew open the stone sealing the sepulcher. What a gift that shroud is to the world. And, by a series of miracles and divine interventions, it has been preserved to this day, despite nearly being consumed by fire. I love that this shroud has since been the inspiration and blueprint for iconographers from the time it was rediscovered.

WOW. Need to reread tomorrow, but just a great post. Learned such important things. Thank you.