Icons Through the Ages: The Changing Face of Byzantine Sacred Art

It's not a single monolithic style

Many western Christians who are not regularly exposed to them have an idea that all Byzantine or “eastern” iconography looks the same.

It’s easy to see why: after 500+ years of adulating the illusionistic naturalism of the Renaissance, the stylized, formal and symbolic aesthetic of Byzantine icons can seem like a foreign world. And I think these stylistic differences are a big part of what keeps the two sides separated.

We westerners, used to our naturalism, tend to not think much about them, and assume that they’re all more or less the same. And it’s true that the forms have a visual stylistic consistency; we know what “Byzantine icons” means. But once you start looking more closely, we see there is a much more complex and historically nuanced development, as there is in western art. Over the centuries, Byzantine iconography changed and developed dramatically, shaped by theological debates, political upheavals and cultural influences.

Our timeframe of iconography stretches across vast temporal and spatial distances, from the earliest frescoes of the catacombs in old Rome to the deeply symbolic, highly stylized icons of post-Byzantine (Constantinopolitan) Orthodox traditions. And it was carried out to the outer corners of the Christian world; we can see the same motifs, the same language spoken, from Ireland, Scotland and Lindisfarne, to Cappadocia to Ethiopia.

In today’s post for all subscribers, we’re going for a wide survey, at what the various periods and schools of iconography were and are.

We will look at the major phases of Byzantine art and see how historical events, theological debates, and cultural shifts shaped the way Christians depicted the sacred.

This, in other words, will be an eye-candy post.

At The Sacred Images Project, we explore Christian life, thought, history, and culture through the lens of the first 1200 years of sacred art. This publication is entirely supported by readers — no ads, pop-ups or distractions — just thoughtful work, funded by your subscriptions.

While The Sacred Images Project has grown into my full-time work, we're now building toward an even richer, multi-layered platform, with plans for e-books, mini-courses, videos and eventually podcasts and more. Your support helps make this expansion possible.

If you’d like to follow along, you can subscribe for free and receive a weekly article exploring the treasures of Christian history, culture, and sacred art..

Paid subscribers ($9/month) receive a second, in-depth article each week, plus additional exclusive posts featuring in-person explorations, high-resolution downloadable images, behind-the-scenes content, and more.

If you believe in the importance of preserving and deepening our sacred patrimony, I hope you’ll consider becoming a subscriber today.

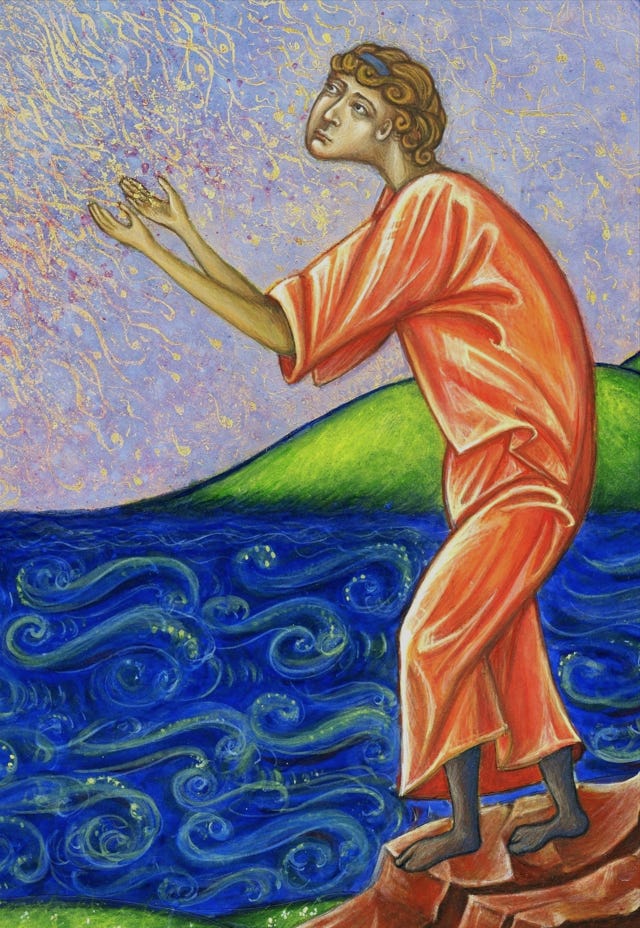

I’m happy to offer prints of this little figure, part of a painting - egg tempera and gold leaf - I did for a client in the contemporary Byzantine iconographic style. He is the speaker in Psalm 84, Quam Dilecta: “My soul longeth, yea, even fainteth for the courts of the Lord: my heart and my flesh crieth out for the living God.”

If you’d prefer to set up a monthly contribution in an amount of your choice, you can also do that at the studio blog, or make a one-off donation to help keep this work going. If you subscribe through my personal page, I’ll add you as a complimentary subscriber here. And thank you.

We’ve covered Santa Pudenziana; read more here.

Byzantine art moved away from the illusionistic space and naturalistic figures of early Christian Roman art, like at Santa Pudenziana - one of the oldest Christian churches in Rome- replacing them with flattened forms, gold backgrounds and a focus on symbolic abstraction. It aimed less at depicting earthly reality and more at revealing heavenly truth.

Early Byzantine Period (4th–7th centuries)

Pre-iconoclasm. Pre-Islam. Between the foundation of Constantinople and the advent of the threat from the Arab peninsula; perhaps not exactly a golden age of Christian unity, what with all the Christological heresies, but at least one of artistic growth, flourishing, codifying and solidifying.

Read more about the imperial mosaics of Ravenna here.

Before the fracturing of Christendom by these twin catastrophes, iconography was a study in imperial magnificence and triumph. This was the time of the great imperial mosaics and churches at Ravenna and Constantinople. The art of the imperial Christian churches reflected the desire of the emperors and their courts to showcase a faith that was both victorious and deeply rooted in the classical past.

The new faith was seeking a distinctive visual language that could communicate theological truths while maintaining connections to the Roman artistic tradition that would have been familiar to most at the time across the empire - a “catholic” language that could communicate to everyone.

This period also saw the development of our standard iconic prototypes that would later become central to Byzantine sacred art and after that incorporated into the western canon, We recognise them today, 1700 years later; the image of Christ as Pantocrator, the Virgin and Child, Anastasis and standard hagiography for the biblical narratives, depictions of saints and martyrs, with their identifying symbols.

Constantinopolitan; a development of Roman naturalism

Christianity, newly legalised and then established as the state religion, emerged from the shadows of the catacombs and into the vast, glittering halls of basilicas and imperial chapels. Icons from this period, the few that survive, still bear the hallmarks of Roman naturalism: the use of perspectival depth and volume and realistic human features, graded shadows for drapery and faces all taking up 3-dimensional space.

Iconoclastic Period (8th–9th centuries) -Crisis and Controversy

The Iconoclastic Period was a turbulent chapter in Byzantine history, marked by intense theological debates and political upheavals, that also started the rift between the east under the emperor, and the west dominated by the papacy.

The core issue was whether sacred images should be venerated as a means of communication between heaven and earth, or removed and destroyed as idolatrous. Iconoclasts argued that depicting Christ in an image was a denial of his full divinity, while iconodules (supporters of icons) insisted that the Incarnation itself made Christ representable. The conflict ultimately split the empire, with emperors often enforcing iconoclasm while monastic communities, in particular, resisted.

Read more about the outbreak of iconoclasm and what it meant, here:

During this time, countless icons were destroyed by imperial orders, and many churches were stripped of their figural decorations. Artistic production slowed dramatically, as many artists and skilled craftsmen - a whole industry - fled, many to come west to seek papal protection. In interior decorations of churches, the emphasis shifted away from images toward symbolic representations like the cross.

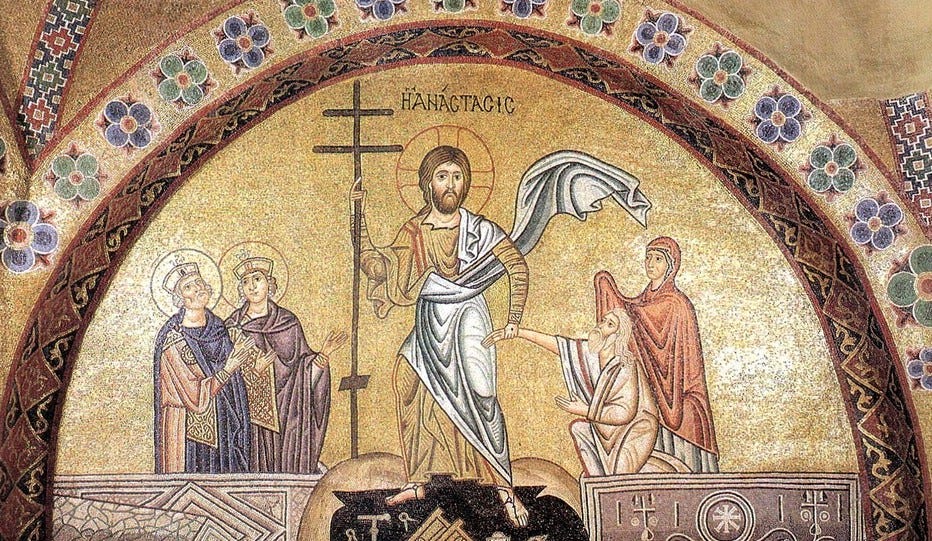

The Second Council of Nicaea (787) marked the temporary end of iconoclasm,, formally affirming the veneration of icons as not only acceptable for Christians but part of the required practice of the Faith - to declare icons heretical was now heresy. However, a second wave of iconoclastic policy occurred in the 9th century before finally ending in 843, a date commemorated to our time in eastern Christianity as the feast of the Triumph of Orthodoxy.

Middle Byzantine Period (9th–12th centuries) - The Revival of Iconography

After the final resolution of Iconoclasm, the Byzantine world experienced a renaissance in sacred art, with the restoration of icon veneration, and a revival of the social and economic prominence of sacred art. This was the time of the development of a more uniform iconographic style that was to become what we now think of as Byzantine sacred art.

This is where our idea that all Byzantine art “looks the same” comes from. The classical naturalism of earlier centuries gave way, after the trauma of iconoclasm, to a more stylized, spiritualised and symbolic aesthetic.

Figures became elongated, more ethereal and less concerned with naturalistic realism. The illusion of perspectival depth was abandoned. Gold backgrounds or flat colour for backgrounds became ubiquitous, symbolising the divine light and timeless space of heaven.

Theologically, icons were now seen as vital for conveying theological truths. The doctrine established at Nicaea II affirmed that icons were not merely art but visual theology, a direct, personal encounter with God and heaven. The new stylised artistic language aimed to portray spiritual reality rather than imitate the natural world or create an illusion of seeing through time.

Macedonian and Komnenian Renaissances (10th–12th centuries)

The Macedonian dynasty (c. 867–1054) launched what would come to be thought a golden age for the Byzantine Empire, with territorial expansion and recovery of lost territory, increased trade and economic prosperity and cultural flourishing. Named after Emperor Basil I “the Macedonian”, who helped revive classical learning and the arts, it is often called the Macedonian Renaissance. The empire regained some lost territories and the capital, Constantinople, became a thriving centre of Christian culture and scholarship.

The Komnenian dynasty (11th and 12th c.) continued this cultural renaissance, while increased contact with the West during the Crusades brought new artistic influences into the Byzantine sphere, and took the Byzantine work into the west.

The Komnenian style is marked by emotional intensity and dynamic, fluid compositions with everything looking as though it’s moving.

Komnenian icons have a sense of heightened drama, even when the figure is still, with bold colours, sharp lines and angular features, and dramatic facial expressions, especially for the Passion scenes or depictions of the Virgin.

Palaiologan sophistication - 1261 - 1453

After the catastrophe of the Sack of Constantinople in 1204 during the Fourth Crusade - that included the theft of much of its precious artistic and religious treasures - in 1261 the city was reclaimed by the Byzantines after 57 years of Latin occupation.

Palaiologan St. Michael panel icon

This icon of Archangel Michael is a fine example of Palaiologan-era iconography, 14th or early 15th century.

Expressive naturalism: The face of Michael is still idealised and stylised - this isn’t “realism” in our sense - but shows a soft modelling of the cheeks and a more human, emotionally accessible expression.

Elegant line and restrained detail: The treatment of the garments, especially the rhythmic folds and subtle highlights, shows grace and movement without losing the icon's contemplative stillness or symbolic symmetry.

Complex symbolism: Michael holds a transparent orb inscribed with Greek letters (Α and Ω) and a cross, signifying Christ’s cosmic authority.

Use of shading and colour layering: There’s more depth and layering of colour here than in earlier, flatter styles. The wings are delicately feathered, and the hair is given volume, softness and gloss.

Emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos made a triumphal entry - chasing out Baldwin II, the puppet emperor of the “Latin Empire” - and founded the Palaiologan dynasty. The city was in ruins and depopulated, but its recovery marked both a political and cultural turning point for all of Eastern Christendom.

The Palaiologan style, beginning after the recapture of Constantinople in 1261 and carrying forward to today, builds on the Komnenian movement with greater elegance and complexity, and starts leaning back towards more naturalistic figures, more believable drapery, etc.

Figures are less stiff and more naturally fluid, colours richer and compositions more layered with more attention to perspectival believability. There’s a shift toward lyrical, almost poetic feeling while remaining deeply theologically symbolic.

Even as the empire’s political and military strength declined, its visual language continued to grow in depth and complexity. The Komnenian and Palaiologan periods weren’t a slow fade but a conscious refinement, artists working within tradition, not against it, developing new ways to express old truths. This was the art of a culture still thinking theologically and visually at a very high level, and teaching the whole Christian world, east and west, through image equally as through text.

Even in a shrinking empire, the icon painters, mosaicists and church decorators of the Komnenian and Palaiologan periods were shaping how all Christian generations to come would imagine sacred reality.

Hilary, this is a fantastic discussion of Byzantine art, a subject I didn’t know much about before reading about it here. It’s also visually stunning. Thanks.

This was so informative and enriching, thank you 😊