Mary, Queen of Heaven or Tolkien's Varda, queen of the Valar?

A conversation about AI and sacred art

This is not Mary, Queen of Heaven

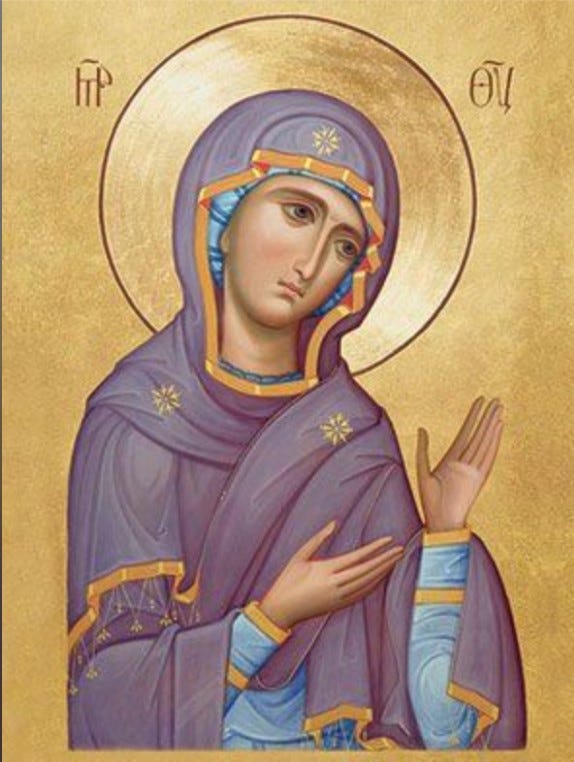

Yesterday was the feast of the Queenship of Mary, in the Latin Church’s liturgical calendar. A priest1 whose feed I follow with interest posted the following image on Twitter, with the caption: “My soul proclaims the greatness of the Lord, and my spirit rejoices in God my saviour, for he has looked with favour on his lowly handmaid. From this day, all generations will call me blessed. The Almighty has done great things for me, and holy is his name.” (Luke 1:46-49)

He intended it as a devotional act, something very common on Twitter and a good and pious thing to do to help inspire, as he said, devotional feelings in his readers.

Well, OK, but who is this, and why do we assume it’s sacred art?

This is not an image of Mary, the Mother of God, Queen of Heaven and all the angels and saints. It might be easily mistaken for her by a pious casual viewer, but look at it for a moment and imagine it was created by a big Tolkien fan. Now it's just as easily Varda the star kindler, right?

In fact, look at it carefully. Do you see any Christian symbolism at all? Any visual markers whatever that this is Mary of Nazareth, the Mother of God? The more I look at it, the more it looks like the kind of Tolkien fan art you’d find on DeviantArt or intended for a video game; it’s nerd art. I actually think it probably is supposed to be Varda, wife of Manwe and queen of the Valar2.

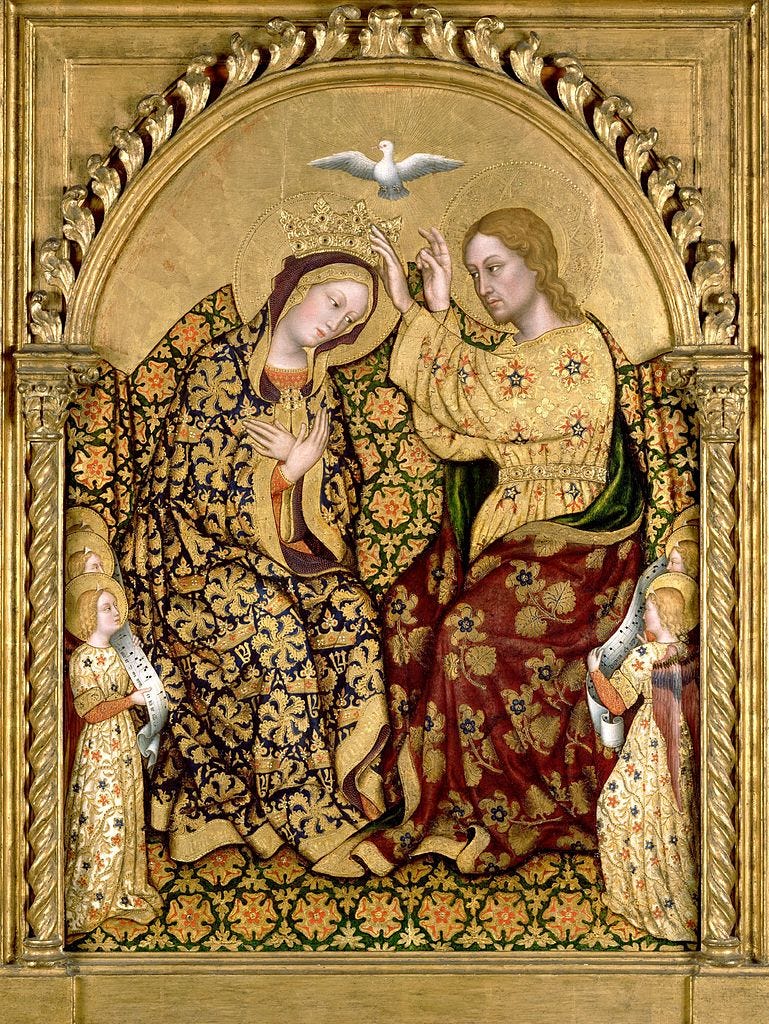

Why the identity is important: idolatry is bad, even if it’s accidental

Canonical Christian sacred art always includes a set of symbols that tell you without doubt who is depicted. And this is much more important than you think, since the purpose of sacred art is worship. Which isn’t the generation of "pious feelings.” It's there to present a particular person - the Theotokos, a saint or Christ Himself - for our veneration - for prayer.

I hope you’re enjoying these posts and find them helpful and interesting. I am a student of Christian sacred art, both theory and practice. You can see some of my drawings and paintings at this site. At the moment commissions - which are slow - and donations are my only means of support. You can join the small group of regular patrons keeping the lights on and me and the kitties fed, at this site, my studio blog,

for just US$10 per month.

No, it’s not idolatry. We don't venerate or worship a lifeless object - the wood and paint and gold - but the specific living person depicted by these worthy materials through the hand of a believing painter, which is why it’s really important to know exactly who it’s an image of. We don’t pray to the painting, but we also don’t pray to Varda.

This is why in Christian iconography the figure is either identified by the hagiographic symbols - like the Lamb for St. Agnes - or by straight up writing the name of the person on the surface of the painting.

These requirements for iconography came out of the great upheaval of the Iconoclastic Controversy in the 8th and early 9th centuries, in which Jews and Muslims started accusing Christians of idolatry for their veneration of icons in the liturgy. Idolatry is bad, so we made rules for iconography that guarantee we know exactly who we’re praying to, because praying is not make-believe.

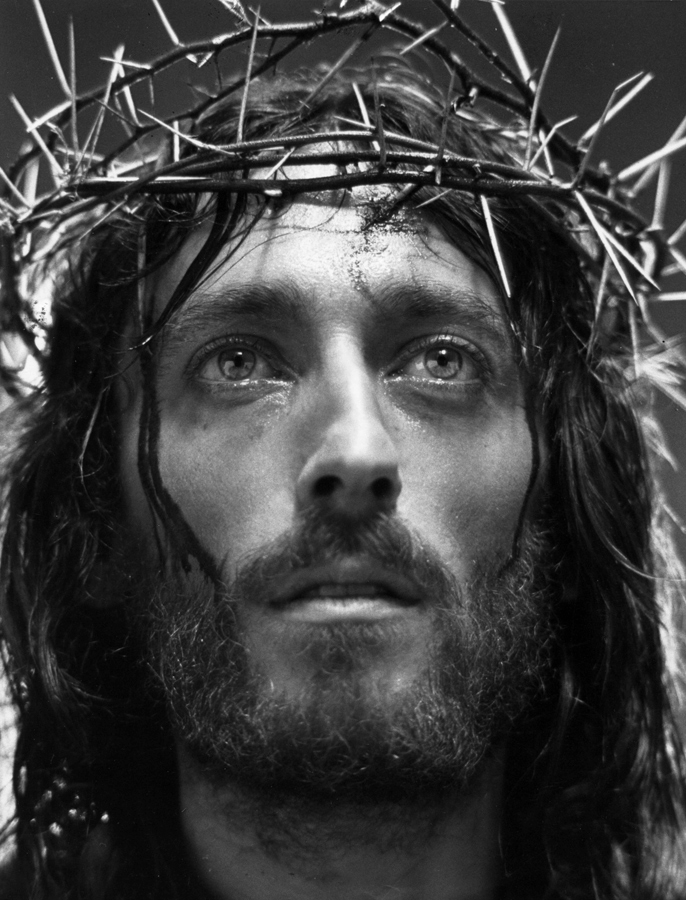

A few weeks ago we discussed these problems. Even before artificial image generators came on the scene, we had what I call the Robert Powell problem in iconography.

You're supposed to go to the movies and think you're there in the action…But it's a psychological illusion, and you're expected to understand the difference between the onscreen images and reality. You're supposed to "suspend disbelief," willingly and to know the difference between the fantasy of the film and real life in the theatre lobby.

The problem comes in when you take a movie still like that, and use it to create works of art intended to depict Christ Himself, not the actor who played Him.

There are churches all over in which pictures of the English actor Robert Powell are printed, framed and proposed for liturgical veneration, because he played Jesus in a very famous film in the 1970s. But if the image presented as Christ is, in fact… in actual reality, the reality we all live in… someone else, who are we really praying to? Really? If the image presented for our veneration is not in reality God at all, is that a form of idolatry?

Can an AI programme create sacred art?

So, what can we make of images that are entirely artificially constructed, without a human mind or hand creating it, even on an iPad with a digital painting programme?

On Twitter, an illustrator and promoter of contemporary Catholic sacred art named John Herreid responded to Fr. Tom’s post saying, “This is AI art, not art created by human hands. I don't think it is appropriate for devotional use.” The response from several people made it clear that we’re in an uphill battle: “Well, the image is beautiful and makes people have pious feelings,” was the gist of it.

Someone on that thread illustrated the problem by writing, “Much of what we see generated with AI is actually beautiful. It is just a different, more remote form of creating, even if the most beautiful of traditionally created art is still more beautiful than AI.“

And this is a big part of the problem. People who don’t really know what art is to begin with really especially don’t know how AI images are generated. They think it’s just some fancy new way for artists to create “digital art”. That is, a new kind of programme used by artists to electronically “paint” their work, manipulating a stylus or a mouse on an iPad or similar device.

But this is absolutely not the case. No human hand, eye or mind had anything to do with the creation of the image above. It was created in response to a verbal command typed into a thing like a search window.

Automatically generated AI images are entirely created by a computer programme. They not only don’t involve a human artist, the program completely precludes any artistic involvement by a human. The only input from a human user is typing a verbal description of the image they’re hoping to get, called a “prompt.” If that user wants to alter the final image, he has to download it and then insert it into something like Photoshop3.

The reality of the image above is that it isn’t even a real image of a person, even an imaginary person. It’s a collection of colours and shapes that the AI produces to approximate the parameters of other images of people. It’s entirely fraudulent as an image of a woman.

Sacred art isn’t just pretty pictures, and veneration isn’t about pious feelings

“Sacred art is an offering back to God using human craft and talents. It is a form of worship. AI art does not contain any of those aspects, and is a computer-guided simulation of worship…I think it is similar to asking a computer to pray, and regarding what it generates as an authentic expression of worship. It’s self-contradictory.”

This is the traditional idea about Christian sacred art that is so ancient it predates the distinction between east and west in the Church: it is a form of worship. Not only to look at, but to create, and the AI cannot worship.

Christian sacred art, we must apparently now clarify, is an image created through the application of a human mind and will for the purpose of the worship of God directly or through the veneration of holy persons. These acts of worship and veneration are objectively real, and not dependent on having pious feelings. Sacred art is a form of visual theology, and a liturgical or devotional object, a sacred object itself, on the level of a sacred relic, crucifix or book of Scripture.

“Icons... are to be kept in churches and honoured with the same relative veneration as is shown to other material symbols, such as the 'precious and life-giving Cross' and the Book of the Gospels.”

Second Council of Nicaea, AD 787

And this is where we run into problems for contemporary western Christians who have in effect, forgotten what sacred art is for and what worshipping God through it means. The person who posted the image of Varda above said that it was intended to “stir devotion” in his followers on Twitter. But if we can’t even be sure the image is of a heavenly person - or even a person at all - what is actually being generated? Is it anything more than emotions? And if we are only enjoying our feelings of piety, isn’t that what we’re worshipping?

Someone responded to the Varda image pointing this out: “Devotional art gains its force from being created by the Imago Dei, which AI does not have!” To which he received the response, “This simply isn’t true. Devotional art has value and effect if it stirs the mind and heart to think of and love God more. This image of the Blessed Virgin does that for me, so it’s just as valuable to me for my piety as any other image of a saint.”

So we can see that what we have here is a problem of unmatched categories; the parties are talking about two entirely different sets of conceptual frameworks.

Fr. Tom Bombadil’s response represents the modern, that is post 1500, Latin Catholic view that the painting over the altar is decoration intended to illustrate some theological idea and generate pious feelings. John Herreid’s stance above, that sacred art is a form of visual theology, active right worship, - an echo of the Fathers of the Church and the Ecumenical Councils - has been lost in the western Church, obsessed as it has been with materialist rationalism, and therefore unconcerned with mystical theology, for 500 years.

In a Church that exclusively equates orthodoxy with meticulously formulated verbal expressions of dogma in response to heresy, the pious person has been left essentially to his own devices to figure out how to actually worship God. We might have orthodox teaching, but if no one is taught a matching orthopraxy, what good is it?

The AI isn’t an intelligence and doesn’t have a will: intentionality

The issue at the core of all this is intentionality; as I said above, the AI can’t worship God. A computer programme, therefore, can’t have the intention of creating a work of Christian sacred art - an image intended for the veneration of the faithful - because it doesn’t have will. We call it “artificial intelligence” but in fact it’s only analogous to a human intelligence. The AI doesn’t have the two aspects that mark a being infused with a rational soul, a human: intellect or will.

As one observer on Twitter put it:

“I actually don't think it's philosophically possible for AI-created images to be considered ‘art’ per se. You might theoretically have an aesthetically pleasing AI-generated image, although I have certainly never seen one, but at best it would be an ‘art-like object.’

“I take it that fundamental to the creation of art is making decisions about its creation that are aimed at producing a certain aesthetic/formal/emotional effect. An AI has no aesthetic sense, all of these terms are nonsense to it, it doesn't even know what its images ‘look like.’

“Yes, a human produces the prompt, but if say a nobleman tells a painter ‘paint such and such a scene with so and so in it’ and the painter does so, we don't then say that the nobleman painted the picture. At most he participated in its creation in a vague sort of way.”

After we forgot how to worship, we forgot what life was for

The core issue of intentionality is a much more important one for us than it first looks, in the age of artificial reality where we are literally unable to tell reality from artifice. We are desperately in need of a grounding in simple, objective reality.

John Herreid wrote later:

“Sacred art is not merely something that makes us feel a certain way. Sacred art is a way in which humans, made in the image and likeness of God, present the work of their hands back to God. AI does not do this."

“What AI does do, is feed parasitically off of the art of human artists. Cut off from that, AI cannot make images. It doesn't create anything, in the proper sense of creativity, which is a human endeavour.

“Final thought is that we all need to gather closer to actual acts of creation: art, music, food, worship, so that we do not lose sight of the human element and end up regarding these things as a sort of remote ‘product’ whose origin does not matter.

I assume it’s really a priest, since he’s anonymous and Tweets with the pseudonym “Fr. Tom Bombadil”.

Interestingly, “Fr. Tom Bombadil” calls himself, “Pastor of St. Elbereth’s Parish, Hobbiton, The Shire.” Elbereth is the name of Varda in Sindarin. I know this because I also am a Tolkien nerd.

After that, we could have a discussion about whether the image is worthy Christian sacred art. But until a person starts to be involved, we’re not even strictly talking about art of any kind.

“In a Church that exclusively equates orthodoxy with meticulously formulated verbal expressions of dogma in response to heresy, the pious person has been left essentially to his own devices to figure out how to actually worship God. We might have orthodox teaching, but if no one is taught a matching orthopraxy, what good is it?”

This is such a beautiful summation of the problem of the Church right now. Thank you!

Perhaps this is too simple, but it seems to me that images like that are "too pretty." There are some

paintings, I know, that are beautiful, like Bouguereau's. But they are definitely created by a man devoted to his Lord. And, of course, not by a device. But this Varda-like image is....well, still, too pretty. And Byzantine-Italo as well as Memling et al. are anything but pretty. How else can one describe it?