The influence of Egypt on Byzantine iconography was subtle but significant, with Egyptian artistic conventions shaping elements of composition, symbolism, and even the concept of the sacred image itself.

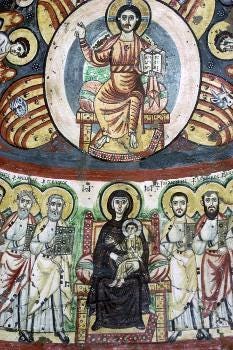

What are the elements of the iconographic image, according to the Egyptian Christian ideal, and what do they mean? Why do they all have those oddly distorted features? It’s on purpose: according to Dr. Zacharia Wahba in, “The Coptic Icons: Their History and Spiritual Significance”:

Large and wide eyes symbolizing the spiritual eye that look beyond the material needs.

Large ears listening to the word of God.

Gentle lips to glorify and praise the Lord.

Small mouths, so that they cannot be the source of empty or harmful words.

Small noses, because the nose is sometimes seen as sensual.

Large heads, which imply that the figure is devoted to contemplation and prayer.

At The Sacred Images Project we talk about Christian sacred art, the first 1200 years. You can subscribe for free to get one and a half posts a week. For $9/month you get an in-depth article on this great sacred patrimony, plus extras like downloads, photos, videos and podcasts (in the works), as well as voiceovers of the articles, so you can cut back on screen time.

~

I will pause to thank the many new subscribers who signed up since I posted my plea, … “A note to our many new free subscribers”. Welcome everyone, and thank you. It’s certainly very encouraging to know that so many find these topics fascinating and are willing to put down hard earned money to know more. Please feel welcome to leave comments below.

We are significantly further ahead in the effort to raise the percentage of paid to free subscribers than we were a week ago, from barely 2% to just over 3%, but this is still well below the standard on Substack for a healthy, sustainable 5-10%.

If you would like to accompany us into our many deep dives into these spiritually and culturally enriching issues, to grow in familiarity with the inestimably precious treasures of our shared Christian patrimony, I hope you’ll consider helping me meet that goal by taking out a paid membership, so I can continue doing the work and expanding it.

This week’s featured print from the Hilary White; Sacred Art shop is the “Duecento” (13th century) St. Francis of Assisi, my drawing of the original Romanesque painting in graphite on paper. You can buy a print that will be shipped to your home by clicking the link.

You can also make a one-time donation or set up a monthly patronage at my studio blog…

When you set up a monthly patronage for $9/month or more (you get to pick the amount) you automatically get a free full-membership here (seems only fair).

You can also browse around the shop where my own work is made available as prints and other items.

Now, back to the show…

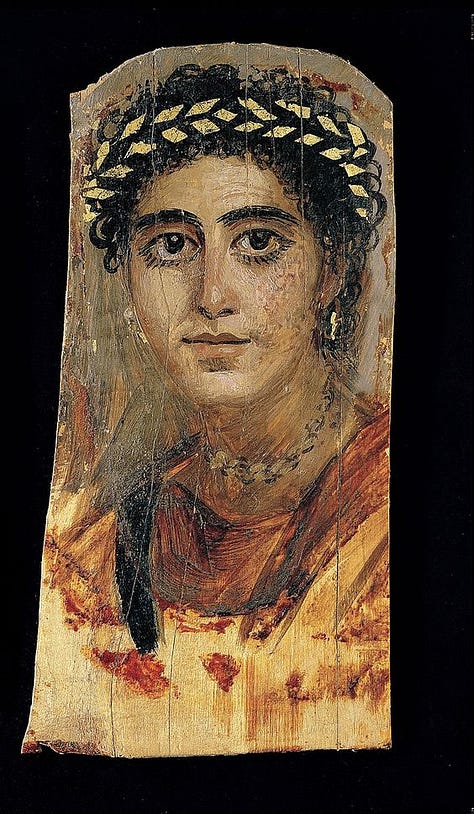

Last week we took a look at the incredible Fayoum mummy portraits. These paintings, lifelike portraits, are contenders for the title of oldest “realistic” portraits we know. They were based on a combination of styles that was typical of the culture of Roman Egypt in general, putting Roman realism together with Egyptian hieratic frontality. (Yes, we’ll define these terms, don’t worry.)

Egypt was important in the Roman and Byzantine Empire, and even more to early Christianity

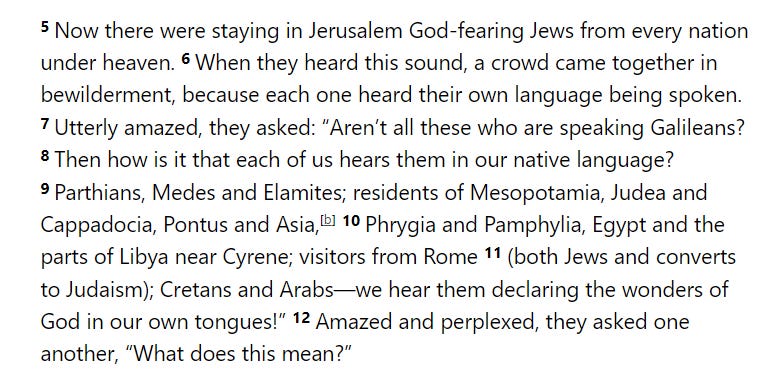

We western, Latin Christians tend to think only of Rome when we think about the very early years of Christianity. But of course, the first disciples of Christ were from all over the Empire, which the New Testament tells us:

Though it is not often remembered now, until its brutal conquest and occupation by invading Islamic Arabs in the 7th century, Egypt was a major centre of Christianity, especially of biblical scholarship.

The first thing to remember about the influence of Egypt on later forms of Christian art is that by the time Christianity came there, Egypt had been an economically and culturally important part of the Roman empire for a century. This means all the empire’s social, cultural and economic interconnectedness was at the disposal of Egyptian Christians for the purpose of evangelisation.

Egypt remained a Roman province until long after the centre of the world had removed to Constantinople. The Byzantine empire was, for over a millennium, the cultural powerhouse, radiating artistic, architectural, and religious influence across the Mediterranean, Near East, and Europe, and that for many centuries, even after the fall of Constantinople.

A quick Egyptian Christian timeline:

Early Seeds (1st Century): Tradition holds that Saint Mark the Evangelist brought Christianity to Egypt, establishing the Church of Alexandria around AD 33.

Facing Persecution (1st-3rd Centuries AD): Despite growth, Christianity faced periods of Roman persecution, with Christians defying Roman gods and emperor worship.

Alexandria's Rise (2nd-3rd Centuries): Alexandria became a major centre for Christian scholarship, with theologians like Clement and Origen influential in shaping early Christian thought.

Monasticism starts (3rd Century): The Egyptian desert became a cradle for monasticism, with ascetics like Anthony the Great - a native of Alexandria - leading solitary lives of devotion.

Constantine's “Conversion” (4th Century AD): The Roman Emperor Constantine allowed the empire-wide practice of Christianity after the battle of the Milvian bridge in 312 AD, ending official persecution.

Coptic Identity Emerges (4th-5th Centuries AD): Egyptian Christians adopted distinct theological positions, particularly regarding the nature of Christ, leading to the term "Coptic" emerging.

Council of Chalcedon (451 AD): A major schism arose when the Coptic Church rejected certain Christological doctrines established at this council, forming the Coptic Orthodox Church.

Monasteries as Centres of Learning (5th-8th Centuries AD): Coptic monasteries continued to be hubs of scholarship, preserving and translating ancient texts.

Arab Conquest (7th Century AD): The arrival of Islam in the 7th century brought a new political landscape, with Egypt becoming part of the Islamic world, and the native Coptic Christian Egyptians taking second-class citizen status and enduring periodic persecution ever since.

Enduring Presence (Today): Coptic Christianity remains the second-largest religion in Egypt today, with a rich history and cultural influence.

Egyptian/Greek Christian influence on Christian scholarship

Alexandria1 was home to the Septuagint, a 3rd-century BC translation of the Hebrew Bible into Greek. This translation made Jewish scriptures accessible to the Greek-speaking world, which was the dominant language in the early spread of Christianity. And it was in Alexandria that Christian thinkers first started to apply Greek philosophical and interpretive methods to understand the New Testament.

The Catechetical School of Alexandria, founded in the 2nd century AD, became a major centre for Christian learning. Here, theologians like St. Clement and Origen wrestled with theological questions. This school, founded around the mid-2nd century AD led the Christian world in identifying and clarifying Christian doctrine, and attracted students from across the Mediterranean world.

The Alexandrian approach emphasized allegorical interpretation of the Bible, seeking deeper spiritual meaning beyond the literal text. The use of Greek philosophical methods allowed Christianity to be presented as a rational and intellectually respectable religion.

Egyptian Christian fun-fact:

The word “Coptic” refers to an Afro-Asiatic language that is directly descended from the language spoken by the ancient Egyptians. Coptic Christians are ethnically the true Egyptians. This language largely became extinct as a spoken language since the 16th century, but survives as the liturgical language of the Coptic Church.

Egypt and Iconography

A key concept in all Christian iconography is “hieratic frontality”. It describes a specific way of portraying figures, particularly in religious contexts. It combines two key elements:

Hieratic: This word comes from the Greek "hieratikos" meaning "priestly" or "sacred." In art, it refers to a style associated with religious figures or scenes. Hieratic art often emphasizes formality, symbolism, and a sense of order.

Frontality: This simply means a figure is depicted facing directly forward, looking straight out at the viewer.

So, when we combine these two elements, "hieratic frontality" describes a portrayal of a religious figure where they are:

Standing or sitting directly facing the viewer. This emphasizes their importance and creates a sense of direct connection with the observer.

Presented in a formal, stylized manner. This could involve rigid posture, symmetrical composition, and minimal movement.

The purpose of hieratic frontality is to convey a sense of awe, authority, and otherworldliness. The figures are not meant to be seen as ordinary people, but rather as representatives of the divine or the sacred realm. Similar to Egyptian pharaohs depicted in profile, Coptic and Byzantine icons often portrayed religious figures frontally, emphasizing their importance and connection to the divine.

Clear connections between ancient Egyptian art and later Christian Egyptian iconography can be seen:

Large Eyes and Symbolic Details: Egyptian art used large eyes to convey life force and power. This emphasis on eyes carried over to Byzantine icons, highlighting the spiritual presence of the figures. Additionally, both cultures used symbolic details, like specific clothing or objects, to convey meaning.

Hierarchical Scale: In Egyptian art, pharaohs were depicted larger than others signifying their elevated status. This concept of hierarchical scale influenced Byzantine icons, where holy figures were often larger than surrounding figures.

These images, some of the earliest icons to survive, are clearly traceable from the Fayoum style. If you took the Fayoum portraits and “abstracted” them, taking out the naturalistic elements, and rendering them in a more stylised, geometric way…

… the relationship becomes clear. Not all Fayoum portraits were very naturalistic either, and in these you can see the connection even more clearly.

Some scholars point to even more ancient Egyptian works for connections to standard Christian iconographic prototypes:

Is there a historical artistic connection between this image, with its familiar gestures, and this?

If the ancient Egyptian was aware of ‘art’, it could not have been above the consciousness of his religious experience. Egypt was profoundly influenced by a belief in the existence of all pervading, invisible and superhuman forces...only continuous worship of these mysterious powers could keep the universe in a equilibrium favourable to the survival of man and his institutions.

Whether these ancient Christian Coptic images are directly stylistically linked to the pre-Christian Egyptian traditions of sacred art has been discussed by Sr. Petra Clare, an Oxford-trained Greek Orthodox iconographer.

She writes:

‘Art, in the sense in which that word is generally employed today, did not exist in ancient Egypt. If the ancient Egyptian was aware of ‘art’, it could not have been above the consciousness of his religious experience. Egypt was profoundly influenced by a belief in the existence of all pervading, invisible and superhuman forces...only continuous worship of these mysterious powers could keep the universe in a equilibrium favourable to the survival of man and his institutions.’

The reigning Pharaoh was responsible for restoring the harmony (maet) of the world ‘as it had been established in the First Time, but which could easily be jangled out of tune by human neglect or wrongdoing. ‘Art for the ancient Egyptian had the secondary meaning ‘skill in execution’, in particular, a superior ability to fashion material things with tools.’

The inseparability of the physical world, religion and making “art” (in terms of being a skilled craftsman) was therefore at the foundation of Egyptian society and understanding of the universe. I think it is this foundational understanding of that interconnectedness that has been passed along to the traditions of Christian sacred art, through Egypt’s conversion to Christ.

Sr. Petra Clare again:

The creativity of art was connected with the creative process by which the universe had come into being. Ptah (the creator god) was depicted fashioning mankind ‘with his two hands as a balm to his heart’ and was symbolised by the primordial mound of earth emerging from chaos, just as the earth of the book of Revelation. Many craftsmen also held priesthoods in the local cults, and this was particularly important in the cult of Ptah, the creator - craft was seen as working in a special relationship with the creator God.

Egyptian religious art, both pre and post-Christian reflects their belief in the inseparability of the divine nature with physical creation, and the absolute necessity of human involvement in the making of religious art to express that invisible connection. Religion without art would be meaningless to the Egyptian mind, Christian or not.

Thanks for reading all the way to the end. This was a free post so it’s easy to share, send it to friends who might enjoy it, or post to social media:

Founded 331 BC by Alexander the Great to be a centre of Greek culture in his newly conquered territory, and as a major trading port.

I was blessed to grow up in Boston in a better season. I spent hours and hours at the Museum of Fine Arts which had an amazing Egyptian collection. The mummies from the Greek period always stopped me in my tracks.

There is definitely something to the link between the sacred/divine and creativity that earlier cultures get right, that our modern world has gotten so very wrong. The direction most "art" today has gone is very stark evidence as to what happens when we intentionally sever the link between our creativity and our relationship with God.