(Saturday) Goodie Bag for July 27: Dog-headed saints and other iconographic oddities

Sorry we're a bit late, and a bit slow

This week’s Friday post is appearing on Saturday for the reasons I mentioned before…

namely…

Yes, we’re in the middle of our second July heat wave, after a few days respite. It’s making things quite difficult. I’m finding there are only a few hours a day it’s possible to work, so posts are going to be done in little bits and will have to be published whenever they’re finished.

I’m hoping to have our exploration of the great Maesta of Duccio di Buoninsegna ready by Monday. The photos and video clips I got when we were in front of it (in its blessedly climate controlled room) are ready, so it will be mostly an eye-candy post for our paid subscribers.

For the same reason we’re not going to have a paid section of today’s post either. I just couldn’t get it put together this week in time to publish, even on Saturday. Sorry. The weather looks like it’s going to be holding steady for at least another week, so we’re in slow motion for the foreseeable. Thanks for your patience.

Benedictine Book Club

Our paid members, however, are invited again to join us for our ongoing discussion in the Substack chat of Abbess Cecile Bruyere’s book, “The Spiritual Life and Prayer According to Holy Scripture and Monastic Tradition.” We are exploring what is really meant by prayer in the contemplative sense, how to pursue it and what it all means.

I’ll be restarting a new thread at the start of each week, and that will be sent out to paid members via email to make it easy to find. One click.

Subscribe to join us.

The Sacred Images Project is a reader-supported publication where we talk about life, culture and Christian thought through the lens of the sacred art of the first 1200 years. It’s my full time job, but it’s still not bringing a full time income, so I can’t yet provide all the things I want to and am planning for. You can subscribe for free to get one and a half posts a week.

For $9/month you also get the second half of the Goodie Bag, plus a weekly paywalled in-depth article on this great sacred patrimony, plus extras like downloadable exclusive images, ebooks, mini-courses, photos, videos and podcasts (in the works).

If you would prefer to set up a recurring donation in an amount of your choice, or make a one-off contribution, you can do that at my studio blog:

Iconographic oddities and strange stories

St. Christopher the dog-headed giant

Thursday was the (traditional calendar) feast of St. Christopher, and I was reminded of the strangenesses of the depictions of him in traditional iconography, and the mystery of his origins.

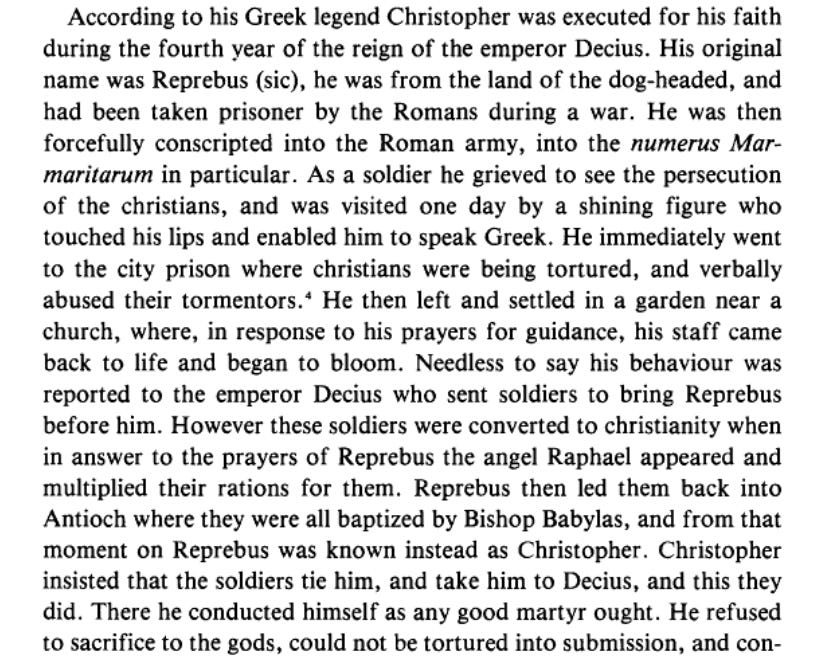

Christopher’s story is set during the reign and persecutions of Diocletian, or possibly Decius. The story speaks of a man named Reprebus, (“the reprobate” or “scoundrel”) who was a giant with a head like a dog’s, captured by Roman soldiers who were at the time fighting against tribesmen of Cyrenaica (then part of Egypt). Reprebus was forced to join the Roman army. On his travels he met St. Peter of Alexandria, one of the earliest patriarchs, who baptised him. He was martyred some time between 250 and 300.

This portrayal is known as the Cynocephalic St. Christopher, from the Greek words "kynos" (dog) and "kephale" (head), and it has roots in Christian hagiographic tradition and ancient mythologies.

As an icon of St. Christopher, the depiction goes back to the earliest times in Byzantine iconography. It was banned as a-historical by the Moscow patriarchate in the 18th century.

The specific depiction of St. Christopher as a cynocephalus appears in some medieval texts and iconography. According to one legend, Christopher was a member of a tribe of dog-headed people. After his conversion to Christianity, his appearance was transformed into that of a human, symbolizing his spiritual transformation.

The cynocephali, or dog-headed people1, are part of a broader ancient tradition from Greek mythology that includes depictions of monstrous races and fantastic creatures. These myths from ancient Greek literature and geography, found their way into medieval legend eventually.

These legendary creatures were written of by Herodotus (5th century BC), who describes them in the context of his exploration of the unknown regions beyond the Mediterranean. Ctesias, a Greek physician and historian (5th century BC) served at the Persian court and wrote about the cynocephali in “Indica.” He said they live in India, and were fierce warriors who communicated through barking and hunted wild animals for food. Pliny the Elder, in “Naturalis Historia” (1st century AD) compiled various reports from earlier Greek and Roman sources. He mentions the cynocephali as inhabitants of regions in India and Africa.

"They speak no language, but bark like dogs, and in this manner make themselves understood by each other. Their teeth are larger than those of dogs, their nails like those of these animals, but longer and rounder. They inhabit the mountains as far as the river Indus...They understand the Indian language but are unable to converse, only barking or making signs with their hands and fingers by way of reply... They live on raw meat. They number about 120,000.

"The Cynocephali living on the mountains do not practice any trade but live by hunting. When they have killed an animal they roast it in the sun. They also rear numbers of sheep, goats, and asses, drinking the milk of the sheep and whey made from it."They exchange the rest for bread, flour, and cotton stuffs with the Indians, from whom they also buy swords for hunting wild beasts, bows, and arrows, being very skilful in drawing the bow and hurling the spear. They cannot be defeated in war, since they inhabit lofty and inaccessible mountains. Every five years the king sends them a present of 300,000 bows, as many spears, 120,000 shields, and 50,000 swords.

“They do not live in houses, but in caves. They set out for the chase with bows and spears, and as they are very swift of foot, they pursue and soon overtake their quarry.

“They are just, and live longer than any other men, 170, sometimes 200 years."

Ctesias

How long had this relationship between remote mountain hunter-gatherers and the civilisations of India been going on when Ctesias arrived? We probably won’t ever know.

To the Canadian icon carver Jonathan Pageau, the association of St. Christopher with the strange, the foreign, the fantastic and unknown, is a symbol of the power of Christ to bring complete outsiders - even monsters - into the Kingdom of Heaven.

Saints Achrakas and Augani, the dog-headed servants of St. Mercurius

Found another one. St. Mercurius (martyred c. 250) is venerated in the Coptic church, and is believed to have been the Roman soldier who killed the emperor Julian the Apostate. This little painting held by the Coptic museum in Cairo, is believed to depict his two cynocephalic servants or companions.

~

Why is Mary sitting in a tree? - Burning mystery of the Theotokos

Icons of the “Mother of God, the Unburnt Thornbush” started appearing very early in the Christian era, and is one of the most theologically beautiful iconographic prototypes, and it’s a great pity it is almost completely forgotten in the west. It is one of the most important icons for bridging the Old and New Testaments, and for showing the place of the Mother of God as embedded at the core of salvation history.

There the angel of the Lord appeared to him in flames of fire from within a bush. Moses saw that though the bush was on fire it did not burn up. So Moses thought, “I will go over and see this strange sight—why the bush does not burn up.”

Exodus 3:2-3

We all know the story: Moses encounters a bush that is engulfed in flames but is not consumed by them. God speaks to Moses from the bush, revealing Himself and commissioning Moses to lead the Israelites out of Egypt. The “Unburnt Thornbush2” is taken in the east as one of the titles of the Virgin. The icon is a visual expression of the Byzantine hymn, or Akathist, of the Virgin Mary, a liturgical hymn very similar in purpose and style to the Litany of the Virgin in the west, though more closely related to the regular liturgy than our special-occasion litanies.

The glorious myst’ry of your childbirth

Did Moses perceive within the burning bush…

…O undefiled and all-holy Virgin.

Therefore we extol you in hymns unto the ages.

Both the bush and the Virgin contained God without being consumed. The icon illustrates the theological concept of Mary's perpetual virginity and her role as Theotokos, the Mother of God, as well as emphasising Christ’s role in salvation throughout human history. Though pre-incarnate, Christ is God, therefore it was He who spoke to Moses out of the burning bush, which the icon makes clear.

The typological reading of the burning bush story, where Old Testament events are seen as foreshadowing New Testament realities, is a common exegetical practice among the Church Fathers and was gradually crystallised in visual form through the iconography.

The "Unburnt Thornbush" is one of the best examples of the concept of icons as visual theology, intended to instruct and inspire the faithful and to bring heavenly realities into this world, or erase the distance between this world and heaven. It very specifically declares Mary’s perpetual virginity, making visual the dogmatic teaching that she remained virgin before, during and after the birth of Christ, the pure and perfect vessel for the Second Person of the Holy Trinity.

It shows the objections of the Protestants to be unscriptural nonsense, derived first from a failure to understand the role of the Old Testament in relation to the new, but more importantly, to understand who Christ is. Protestant aversion to honouring Mary does not derive from a misunderstanding about her, but about who Christ really is. The problem is their “low” Protestant Christology. To a Catholic it would make no scriptural sense to suggest that Mary and the Righteous Joseph the Betrothed could have got down to the business having children after Christ was born, because we know who He is.

She must be the stainless vessel, kept separate and consecrated to that cosmic purpose: containing and nurturing the pre-eternal God of the universe; Who called all things visible and invisible from non-existence into being through an act of will; Who dwells in unapproachable light; Who walked with Adam and Eve in the cool of the evening; the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob; Who spoke as the nameless and unnameable One-Who-Is from the burning bush.

She is depicted in the icon as the human throne of the eternal God, before Whom the seraphim cover their faces in holy fear as they fly back and forth crying aloud Holy! Holy! Holy! And this is why she is called in the Byzantine liturgy, “more honourable than the cherubim” and “more glorious beyond compare than the seraphim.”

~

The legend of the seven sleepers of Ephesus

One of the strangest and most intriguing stories out of the Christian east is the legend of the “Seven sleepers”. It reads like a fairy tale or a fantasy novel. It has been told and retold many times, starting with the Greek scholar Symeon Metaphrastes, and is common not only to the Christian east and west, but Islam as well. The story persisted through the Middle Ages, appearing in a Norman and even a fragment of a song in Old Norse.

During the persecution of Christians in the reign of Decius, the Emperor himself came to Ephesus, which was a Christian stronghold closely associated with the final years of the Mother of Christ. During this visit, Decius confronted the seven noble youths named (from some sources) Maximillian, Jamblichos, Martin, John, Dionysios, Exakostodianos, and Antoninos. These young Christian men were tried by the emperor and given some time to reconsider their faith. During this respite, they gave away their property to the poor, keeping only a few coins, and went to stay in a cave on Mt. Anchilos, to pray and prepare for death.

When the emperor returned the seven youths heard of his arrival, and as they were praying their last prayer, the all fell asleep. When the emperor was told the seven young men were asleep in the cave, he ordered that the cave entrance be closed with huge stones, so they would starve. An unnamed Christian wrote their names on the stone at the cave entrance.

The emperor Decius died on campaign, and the empire was placed in other hands and became Christian. Two or some say three hundred years passed and the day came when, in the reign of Theodosius, the Christian emperor, heretics in Ephesus denied the Christian teaching of the resurrection of the body. At the same time, the man who owned the land where the cave lay opened it, with a mind to use it as a shelter for animals. Workmen are astonished to see the seven young men, untouched by time, awaken and believe they have slept only one night.

They send one of their number, Diomedes, to go to town to buy some food before they give themselves up for death for Christ, but Diomedes is amazed to see the empire entirely transformed, with Christian symbols on public buildings and the name of Christ uttered aloud. The local people are equally surprised to see the coins minted in the reign of Decius.

It finally comes out that Diomedes had no knowledge of the history of the preceding 300 years, and it is clear that he is one of the lost seven youths, long forgotten. He meets the local bishop who accompanies him to the cave to meet the other six. The emperor Theodosius is sent for, and the youths tell their story to him, and everyone rejoices at the proof of the doctrine of the resurrection of the body. The young men, after discoursing on this, die in the peace of Christ.

An addendum to the story says that the emperor, who had suggested creating magnificent tombs for them, had a dream in which they appeared asking that they should be buried only in their old cave, into which a church was built.

In Ephesus, in Turkey, it is possible to visit an archaeological site on the slope of Mt. Pion called the Grotto of the Seven Sleepers, a Byzantine necropolis where dozens of rock-cut tombs can be seen. A ruined church is carved into the rock. The cave was once lined with bricks and inside the side walls of the church are niches and arched vaults. In the depths of the cave there is an apse.

There are hollows in the floor, now empty, that were tombs. In the cave and its surroundings several hundred graves from the 5th and the 6th centuries AD have been discovered.

There is also an archaeological site with a Byzantine complex and a cave - partly natural and partly man-made - in Jordan near Amman (which, of course, is nowhere near Ephesus), called the Cave of the Seven Sleepers, that has been used for multiple burials since the Byzantine period. The site has remnants of a Byzantine church. Islamic ruins built at the site have been dated to about 700, and scholars believe that the original Byzantine buildings were converted into a mosque after the Islamic conquest. The cave holds seven sarcophagi as well as a number of other burials.

That’s definitely all we can manage this week…

It’s perhaps a good place to note that in the far east of Asia, when western Europeans first started arriving, we were described by Chinese and Japanese locals as looking like dogs or other animals because of the length of our noses and generally strange, three-dimensional, non-Asian look of our faces.

The bush in question is referred to as Senekh, a thornbush, in Hebrew.

Dog saints for the dog days of summer. Very interesting, too. Hang in there!

In the Byzantine “Book of Needs” which contains Sacramental rites, various Services of Intercessions to Saints, consecrations of people and things as well as blessings there is a prayer to the Seven Holy Sleepers to intercede for those with insomnia. In the West, especially in Spain, Sicily and Calabria the Seven Sleepers are invoked for the same malady.