The "Crux Gemmata" - how the Cross was depicted in early Christian art

Below the fold: I'll answer the question, "Where can I find good online drawing instruction?"

The absent corpus? The early centuries

In our time, we are accustomed to thinking of the crucifix as simply a standard symbol of Christianity, an image that adorns churches and sacred objects everywhere. But in the early centuries of the faith, the idea of depicting Christ on the Cross was not as theologically obvious as it seems today. It took centuries for the Crucifixion to emerge as a common devotional subject in Christian art and spiritual contemplation.

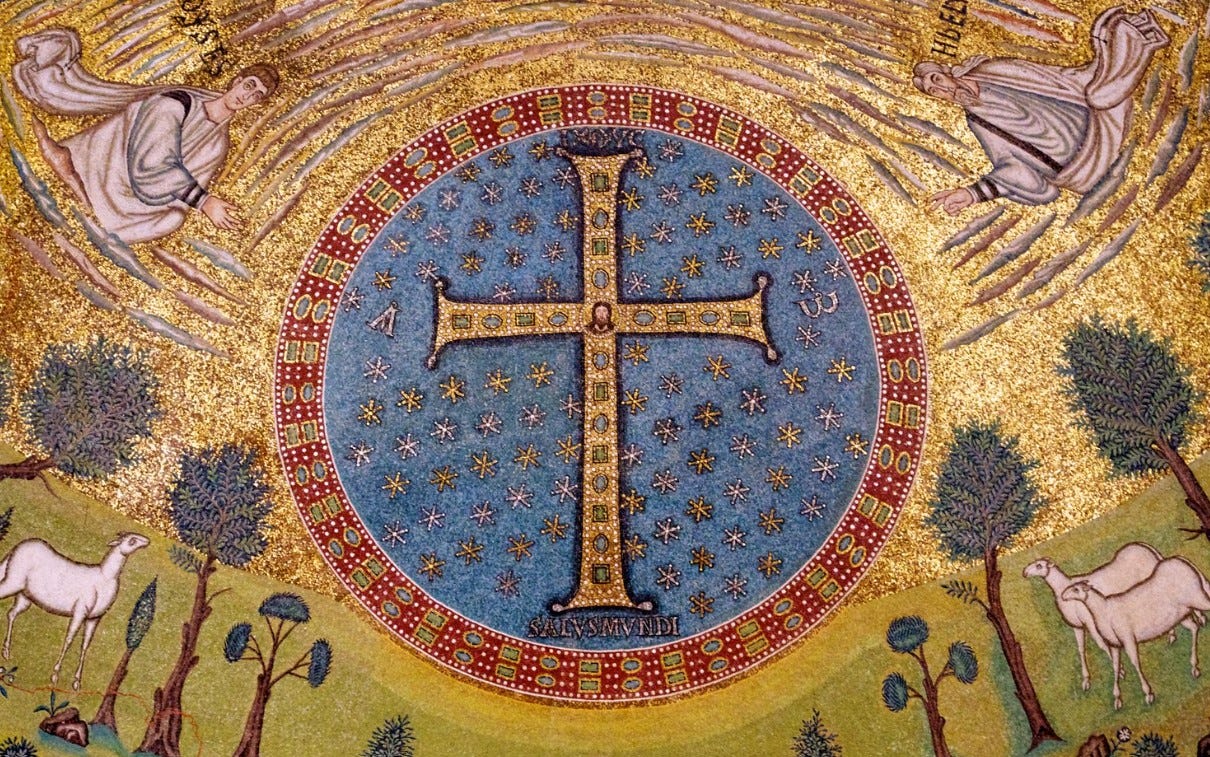

By the 6th century, the time of the creation of the Ravenna mosaics, Christianity had become deeply woven into the fabric of the Roman world, both east and west. The Cross, once a grim and humiliating reminder of brutal execution in late pagan antiquity, had been transformed into a symbol of triumph in the empire’s Christian era. But this transformation did not happen overnight, and Christian art tells the story of this gradual evolution in thought and devotion.

Read all about later medieval developments of the crucifix as a sacred art prototype

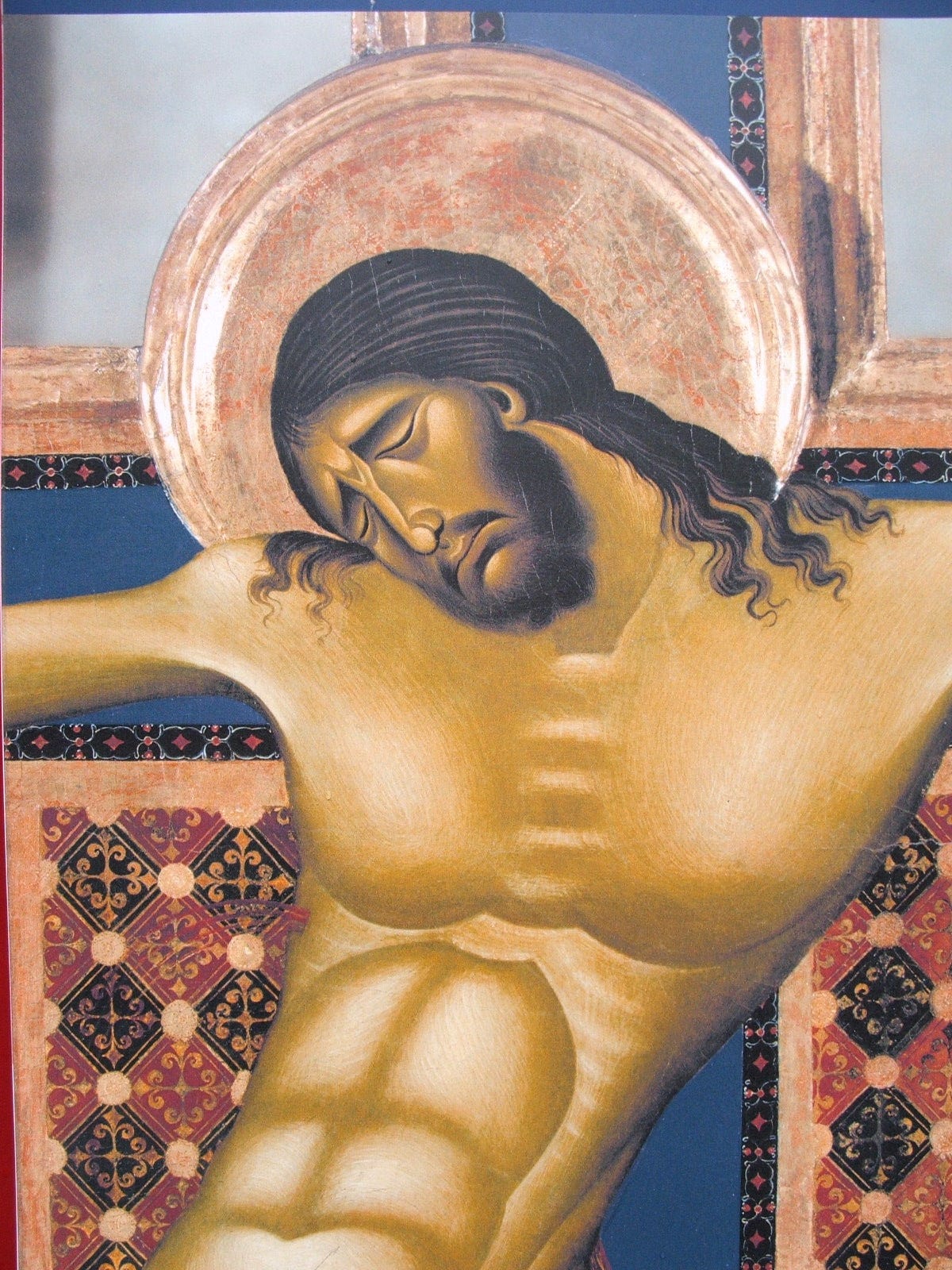

Ecce Agnus Dei: 13th century Umbrian panel crucifixes

When you want to get off the beaten tourist trail in Italy, come to Umbria. We have, among many other under-sung treasures, one of the most captivating art forms anywhere, in the churches and museums of every town; the 13th century - “Duecento” - panel crucifixes of Umbria and central Italy.

Depictions of the Cross and Crucifixion evolved between the 3rd and the end of the 7th centuries in conjunction with the Church’s growing understanding of the nature of Christ as the Second Person of the Holy Trinity, and His salvific sacrifice. The latter end of this period was a time in which Western and Byzantine traditions were beginning to take separate paths and “Italo-Byzantine” was becoming a separate thing from Constantinopolitan sacred art.

San Vitale’s famous 6th century Italo-Byzantine mosaic cycle focuses on the meaning of the Holy Eucharist - using types from the Old Testament, including Abel and Melchisedek, the Hospitality of Abraham and the covenant of Moses - and the sacrifice of the Mass. You can see that the cross is present, but not prevalent.

Crux Gemmata - the “trophy of victory”

One of the things that strikes you when standing in a place like the Basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna, is how familiar it all is. If you are a Christian and the least familiar with the Scriptures, you will immediately know the stories depicted there and how they are connected thematically; Abel and Melchisedek, Abraham and Sarah meeting the three angels at the Oak of Mamre, the sacrifice of Isaac, the encounter of Moses with the burning bush - the repeated idea being the renewal and fulfilment of the covenant between man and God through Christ’s sacrifice.

Even the simpler, “background” decorative motifs convey their deeper meaning; birds and fountains, fruit and vines, all speak to us at a deep cultural level of spiritual realities. These images from our Faith that we share with our contemporaries, we would also share with the people so distant from us in time.

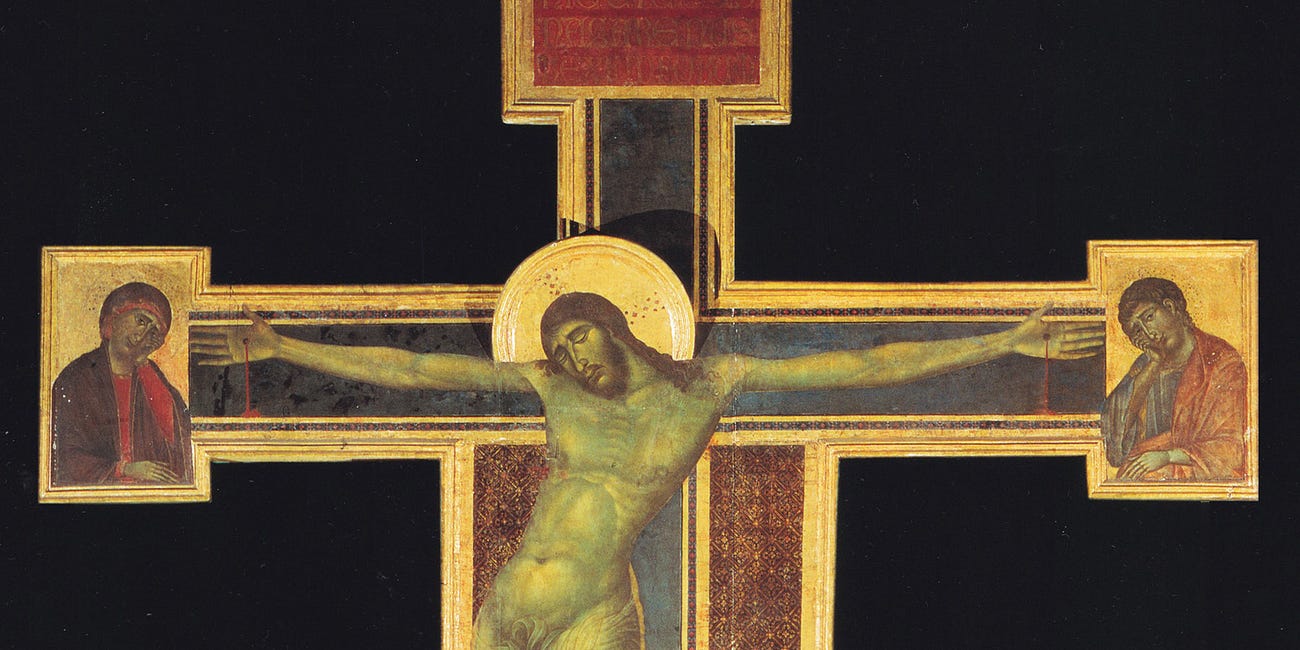

But while much seems instantly recognizable, there is something missing, something so fundamental to our experience of Christian art that its absence seems almost jarring. The Cross is there but it is empty. There is no Corpus. The image of Christ hanging upon the Cross, the Crucifixion scene so central to Christian visual culture today, is not yet the dominant way of presenting the Passion.

Instead, we find something different: a cross that radiates with light, adorned with jewels, or standing alone as a victorious sign.

The Cross was often described as “the trophy of victory” by early Christian authors like St. John Chrysostom and St. Ambrose. This was depicted symbolically as the Crux Gemmata (jewelled cross) as a kind of “tropaion,” (trophy), radiating light, and likening Christ’s Passion to a victory over the forces of darkness.

The Cross of Lothair

One of the most important objects to survive of the Ottonian Empire of the 10th and 11th centuries is this processional cross from the late 10th century, a masterpiece of early medieval craftsmanship, combining imperial and sacred symbolism. The front is an opulent crux gemmata, made of gold, adorned with precious stones, and featuring a central Roman cameo of Emperor Augustus, reinforcing the idea of divine rulership inherited by Christian emperors.

The reverse, in contrast, is a simple engraved drawing of the Crucifixion, likely added in the early 11th century, reflecting a shift in spiritual focus from imperial triumph to Christ’s suffering. This juxtaposition embodies the Ottonian synthesis of earthly power and divine salvation, both a political statement and an object of personal devotion for Otto himself.

With this depiction of the crucified Christ, almost as though hidden from public view, we see the western iconographic stylisation already well developed. This image is very similar to those that were to become standard for painted crucifixion panel paintings in Umbria in the 13th and 14th centuries.

Christological Debates

The 6th–8th centuries were marked by theological debates about Christ’s nature that was reflected in the Church’s art. Ecumenical councils affirmed the orthodox teaching that Christ was fully God and fully man, and art had to convey this truth.

The Council in Trullo (692 AD) provides a striking example1. This council, convened in Constantinople, was primarily concerned with disciplinary canons, but it also addressed sacred imagery. One of its rulings was Canon 82, which decreed that Christ should no longer be represented symbolically as a lamb but should instead be depicted in His human form. The reasoning behind this was explicitly theological: the council wished to emphasize Christ’s Incarnation and His real, historical Passion, ensuring that the faithful understood the depth of His suffering and the reality of His sacrifice.

This ruling marked a crucial period of transition in Christian iconography. Earlier Christian art had often portrayed Christ indirectly, through symbols such as the Good Shepherd, the chi-rho, or the Agnus Dei (Lamb of God). While these symbols remained important in Christian tradition, the council’s decision reinforced the move toward a more anthropomorphic representation of Christ, particularly in depictions of His earthly ministry and His Passion. The ruling was intended to align with the growing theological emphasis on Christ’s dual nature, fully divine and fully human, a key doctrinal issue debated during the Christological controversies of the previous centuries.

The ruling reflects a broader pattern: as theological ideas developed, they were visually expressed in sacred art. The relationship between doctrine and artistic representation was not incidental but deeply intertwined; art was an extension of theology, a means by which the faithful could contemplate and internalise the truths of the faith.

Iconoclastic Divergence

The most important divergence between the liturgical and artistic practices of the East and West was the Iconoclastic Controversy in the Byzantine East that began in the 720s in conjunction with the rise of Islam, that was radically opposed to any sacred art. The Eastern Empire, under some emperors, banned religious images, fearing idolatry, but notably exempted the cross symbol from this ban.

During this period, Byzantine churches often displayed only the cross, not figurative icons. Western Christians (including the Pope and the young Frankish kingdom of Charles the Great) largely rejected iconoclasm and continued to produce sacred images of Christ. This meant that by the late 8th century, Western art was free to develop imagery of the crucified Christ, while the Greek East had a period of minimal new figural art. The result was a gradual stylistic and thematic drift between the traditions: the West fostered continuous innovation in portraying Christ’s Passion in visual theology, whereas the East, after the restoration of icons (843), resumed its own traditional style with an even more carefully controlled and conservative visual theological perspective on how to depict Christ.

By 600–800 AD the stage was set for distinct artistic approaches: the Western church, deeply devoted to the Crucifix and unimpeded by iconoclastic upheavals and further away from Islam, began to embrace images of the dying Christ as catechetical and devotional tools. The Eastern church, though sharing the same faith in the Crucified and Risen Lord, maintained a more guarded, theologically measured artistic tradition, especially emphasizing Christ’s divine impassibility even in death.

The transformation of the cross from an obscure sign, to a resplendent symbol of victory, and finally to the central image of Christ’s suffering, mirrors the development of Christian spirituality itself. It moved from a discreet mark of faith in the age of persecution, to an imperial emblem of triumph, and finally to an image of profound personal devotion.

In the paid section of today’s half-and-half post for free and paid members, we’ll be doing something a little more on the practical side. I get asked very often where people can learn the drawing skills they weren’t taught in schools, and where parents can find practical, skills-based art and drawing skills for their home-schooled children.

So I’ve got some thoughts on the subject of drawing and learning to draw, especially as an intimidated adult, and some debunking of common myths. Then we’ll see some places to look for instructional materials, keyed to all incomes and levels of interest.

A special request

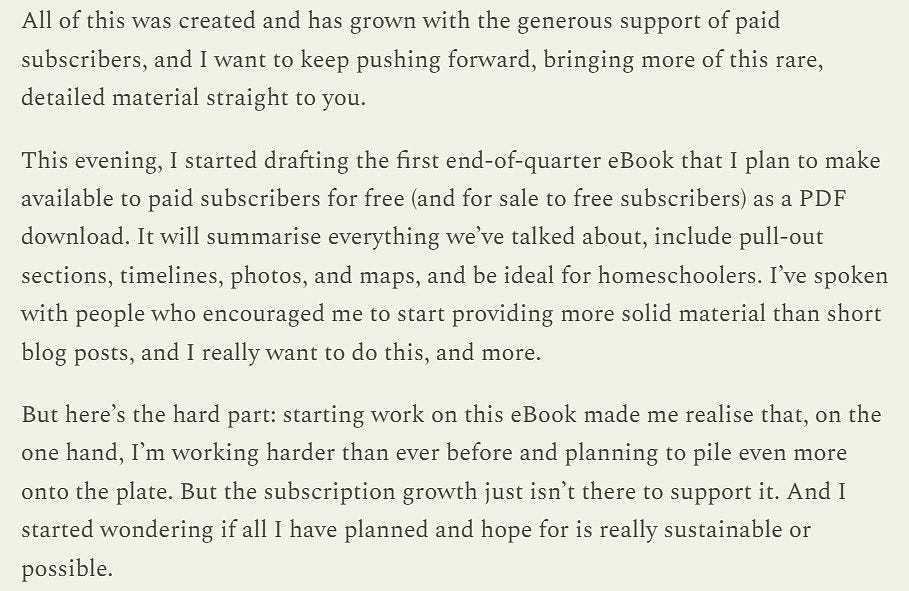

The other day I published an extra post, asking free subscribers to consider taking out a paid membership if they’d enjoyed the material so far, and asking monthly subscribers to upgrade to annual. And I’m very grateful for the response so far:

The Sacred Images Project has been growing fast, about ten new readers every day which is amazing. But while free subscriptions help the community expand, it’s the paid subscribers who make the deep dives, travel-based research, and exclusive content possible. Over the past month, I’ve published in-depth explorations of San Vitale, Torcello, and the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia, plus studies on early Christian art, Italo-Byzantine traditions, and sacred symbolism. And I want to do even more.

I’m working on an end-of-quarter eBook for paid subscribers, packed with summaries, pull-out sections, photos, and maps, ideal for homeschoolers and those looking for a structured deep dive into sacred art. I’m also laying the groundwork for real-world expansion: lectures, seminars, and educational resources beyond just blog posts. But to make that possible, I need more stable support.

If you’ve been enjoying the free posts, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. Your support is what allows this work to continue, and to grow into something even bigger.

Subscribe to join us below the fold