Two Ravennas: Arian and Catholic

Two sets of 6th-century mosaics and what they tell us about theology, empire, and art.

6th century Ravenna and religious coexistence

There are a lot of misconceptions, as we’ve explored, about the “fall of Rome”. One that is probably assumed by many without thinking is that it involved the actual city of Rome. A lot of people are surprised to learn that by the time Odoacer (r. 476–493), the Germanic chieftain, made the last western emperor, Romulus Augustulus, an offer he couldn’t refuse in 476, Rome hadn’t been the capital of the western empire for quite some time.

Milan (Mediolanum) had been the imperial capital under Diocletian’s tetrarchy since 286 and the administration moved to Ravenna in 402 under Emperor Honorius. For nearly three-quarters of a century after Rome’s “fall,” Ravenna remained the western capital, first under the Ostrogothic kings and then under the Byzantines who arrived back on the scene in the 6th century and created the Exarchate of Ravenna.

And it was decorated accordingly. Ravenna’s Imperial mosaics remain some of the most important and famous early Byzantine art works in the world.

When people first encounter these incredible mosaics they’re often surprised to learn that there are two seemingly similar, but theologically different sets of images in the most important churches in town.

We’re going to revisit the grandeur of Ravenna’s mosaics for today’s post for all subscribers, and discuss why this one small city in north-eastern Italy contains two sets of monumental church decorations from the 6th century, that say very different things about Christ. Both are magnificent beyond description, both glitter with gold and brilliant colour; both sets are deeply religious in nature, depicting Christ, the Apostles, angels, saints and rulers, yet speaking two very different theological languages.

Some video I took last February on a flying visit to San Vitale:

Looking at these, being under them gazing up, it’s easier to imagine the brilliance, power and confidence of the Byzantine Empire at its height.

At The Sacred Images Project, we explore Christian life, thought, history, and culture through the lens of the first 1200 years of sacred art. This work is entirely reader-supported. No ads, no algorithms, just careful research and thoughtful analysis, made possible by your subscriptions.

Free subscribers receive a weekly article uncovering the treasures of Christian tradition. Paid subscribers ($9/month) receive a second weekly piece, plus bonus posts with high-resolution images, video explorations and more.

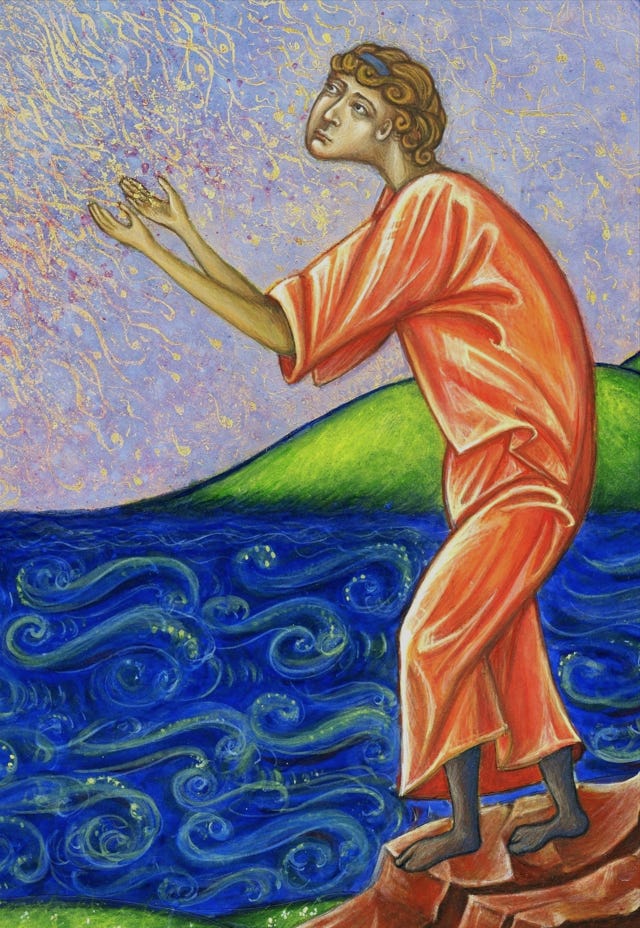

I’m happy to offer prints of my own and historic works, including this little figure, part of a painting - egg tempera and gold leaf - I did for a client in the contemporary Byzantine iconographic style.

He is the speaker in Psalm 84, Quam Dilecta: “My soul longeth, yea, even fainteth for the courts of the Lord: my heart and my flesh crieth out for the living God.”

If you’d prefer to set up a monthly contribution in an amount of your choice, you can also do that at the studio blog, or make a one-off donation to help keep this work going. If you subscribe through my personal page, I’ll add you as a complimentary subscriber here. And thank you.

Italy, an Arian kingdom

What the guidebooks only touch on, but is at the centre of much conflict in the Christian world at the time, is that there were, in its early days as an imperial capital, two rival sets of religious concepts happening in Ravenna that was illustrated in her monuments.

In one church, San Vitale, we see the majestic figure of Emperor Justinian flanked by bishops and soldiers, matched on the opposite wall by Empress Theodora and her court. In another, we see the solemn Christ enthroned above rows of haloed Apostles, all beneath golden arches and palms. But looking closely and with understanding, we learn these aren’t just different decorative iconographic programmes. One belongs to orthodox (Catholic or Chalcedonian) Christianity under imperial Byzantine rule. The other was built for the Arian Christian court of the Ostrogoths.

As simply as possible, Arians believed that because Jesus was the Son of God, He was secondary to and lesser than God the Father. The Father had always existed, but Jesus, they held, was a “a second, or inferior God, standing midway between the First Cause and creatures.” They held that Christ was made, not begotten, and was “arrayed in all divine perfections except the one which was their stay and foundation. God alone was without beginning, unoriginate; the Son was originated, and once had not existed.” Christ, in short, was not divine in the same sense as the Father, not equal in dignity, co-eternal or consubstantial.

Arianism and its many offshoots and sub-genres of heresy plagued the Church with mini-schisms, factions, disagreements and controversy for more than three centuries, long after the Council of Nicaea had formally condemned it in 325.

The Germanic tribes were Arians, not Christians in the proper sense of the word. Arianism had taken root among the Goths in the 4th century through the missionary, Arian bishop and philologist, Ulfilas (c. 311 – 383). He was a Cappadocian Greek who translated the Bible into Gothic - creating the Gothic alphabet for the purpose - and passed on a theology that had already been condemned by the Church.

When Odoacer, deposed the last western emperor, he did so as an Arian. Though he claimed to govern Italy in the name of the Eastern Emperor in Constantinople, Zeno, his religious position put him at odds with the Catholic majority in the West and the East. This marked the beginning of a new and uneasy phase in which Italy was ruled by a non-Roman warlord who held a heretical version of the faith, while the majority of those he ruled, including clergy and most of the old Roman elite, professed the Nicene Creed.

Though not an Ostrogoth himself (he was likely of Scirian origin) his successor continued this problem, though handling it with a certain diplomatic grace.

Theodoric the Great

When Theodoric the Great, (r. 493–526), an Ostrogoth and also an Arian, took power, this religious tension between state and church continued. Theodoric was a savvy and deliberate ruler who sought stability by maintaining Roman institutions and promoted religious tolerance. He allowed the Catholic population to keep their bishops and churches, while commissioning Arian churches for his court and followers.

Theodoric ordered the construction of some of Ravenna’s most impressive buildings, including churches whose mosaics still survive today, like the original palace church, now known as Sant’Apollinare Nuovo and the Arian Baptistery (the former being re-consecrated as a Catholic church in 561). But what guidebooks usually don’t say outright is that these mosaic decorations were specifically non-Catholic theological statements.

Arian Christ and Catholic Christ compared

The Arian Baptistery in Ravenna was built in the late 5th or early 6th century by Theodoric for his Arian court. It was intended for the baptism of converts into Arianism from paganism. Though its mosaics resemble those in Catholic buildings, they reflect a fundamentally different understanding of who Christ is. And if you look carefully, with some knowledge of the theology behind iconography, you can see it.

In the Arian dome, completed c. 500–505, we see a simple, vulnerable, youthful (beardless) and humanised Christ, portrayed more as a “chosen” figure - similar to Saul or David in the Old Testament - than as the eternal Word. In today’s terminology we would say that this is an image reflecting a “low” Christology. It is elegant but ambiguous. It avoids affirming Christ’s coeternity with the Father and lacks any clear Trinitarian hierarchy, with almost no markers of divinity or kingship, just a simple halo. There are no attending angels present as there are in all traditionally Christian Baptism scenes. Instead we see the old pagan archetypal figure of the old man who represents the river Jordan.

The surrounding apostles, carrying their own laurel crowns, form a kind of ceremonial procession, like an honour guard, but there’s no sense of the divine majesty radiating from Christ Himself. In fact, visually, the apostles, clothed Roman senators, look more impressive than Jesus, being somewhat larger in scale.

All this contrasts with the Fathers who identify the Baptism of Christ as a crucial moment of theophany.

The Spirit bears witness to the Godhead; the body of Jesus is baptised, the Spirit hovers above, and the voice of the Father gives testimony. Let us honour today the Baptism of Christ and celebrate it in holiness. More illumination comes to us from this day than from any other.

St. Gregory Nazianzen (c. 329 to 390) Oration 39, On the Holy Lights

The same implied denial of full divinity can be found in the Arian mosaic programme of Theodoric’s palace church of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo. Here, Christ is enthroned, but not in the cosmic, radiant, timeless way we see in the later Byzantine mosaics of San Vitale. Instead, He is a youthful, imperial-looking figure, (this time bearded), on a throne, resembling a glorified earthly king or heavenly messenger.

Notably, this is not the apse mosaic, but is on a side wall; Christ is therefore not the summation and goal of all that exists. In traditional Catholic mosaics, especially in imperial Byzantine contexts, Christ is shown larger, enthroned at the centre with a strong hierarchical composition of scale. The rest of this mosaic, however, depicts Apostles and saints depicted as the same size as Christ, refuting any idea that He is substantially different from them1.

In contrast, the apse mosaic of the Catholic San Vitale - begun under Ostrogothic rule in 526 AD and consecrated in 547 AD under Byzantine rule, after Justinian’s reconquest - presents a cosmic and glorified Christ in heavenly splendour, offering the martyr’s crown to Saint Vitalis. He is robed in imperial purple2; His throne is not a Byzantine emperor’s chair, or an Ostrogothic king’s throne, but the globe of the cosmos. He is flanked in grand estate by angels and framed in heavenly gold.

The four streams of water flowing beneath the enthroned Christ or the Lamb representing the four rivers of Paradise, drawn from Genesis 2:10–14, “A river flowed out of Eden to water the garden, and there it divided and became four rivers…” These symbolise the spiritual abundance of Christ as the new Adam, seated in the restored paradise.

And we see the hierarchy of scale, with the two saints depicted slightly smaller than Christ and the angels. Notably also, the figures of the Emperor, Empress and their court are below and to the side of the apse, and they are shown in the role of servants of the altar, carrying the liturgical vessels.

Though He is still a beardless youth - in keeping with the Roman habit until later - it is a theological image of Christ Pantocrator, the coeternal Son, Judge of the living and the dead, the enthroned ruler and creator of all that exists. It is an unmistakable affirmation of Nicene orthodoxy, rendered in visual form.

Catholic Ravenna - Byzantine revival and conversion of the Goths

The Arian chapter in Ravenna’s history came to an end with the Byzantine reconquest under Emperor Justinian, whose general Belisarius defeated the Ostrogoths in the 540s. With the restoration of imperial authority came a renewed and public affirmation of Nicene orthodoxy and Arian churches were either re-consecrated, like the Arian Baptistery and Sant’Apollinare Nuovo, or gradually faded from use. New churches and mosaics, including those in San Vitale, affirmed the full divinity of Christ and the unity of the Trinity with unmistakable splendour.

Over time, the Gothic peoples in the West converted to the Nicene faith of the Church. The theological ambiguity and imperial rivalry that had once shaped Ravenna’s religious and political landscape gave way to a new era of liturgical unity and artistic flourishing under Byzantine influence.

Today, Ravenna preserves both chapters side by side; in 1996, eight monuments in Ravenna, including the Arian Baptistery and San Vitale, were collectively inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Mausoleum of Galla Placidia (early 5th c.)

Neonian (Orthodox) Baptistery (c. 430)

Basilica of Sant'Apollinare Nuovo (early 6th c.)

Arian Baptistery (late 5th c.)

Archiepiscopal Chapel (c. 500)

Mausoleum of Theodoric (520)

Basilica of San Vitale (consecrated 547)

Basilica of Sant’Apollinare in Classe (549)

Read more about Rome and Ravenna’s imperial mosaics, an expression of the imperium’s devotion to Eucharistic piety, here:

I am so glad I took a trip to Ravenna the last time I went to Italy. And I remember the difference between the Arian baptistry and the Catholic monuments very well. Majesty doesn't quite capture what the apse in San Vitale looks like. I think I stared up at it for like two hours, so much that my neck was sore the next day. Thanks for drawing attention to this.

In the section on the Arian vs Catholic images of the Baptism of the Lord, I think you accidentally pasted the same image twice.