What's wrong with this picture?

We worship God, not stone or wood: why Christian sacred art can't be Naturalistic

“There is a mania right now in the ascendant factions in the Vatican for demonstrating how up-to-date they are, particularly in the area of modern communications technologies.”

“We have a philosophically corrupted visual culture in the modern western Church, and have to find a way to bring it back from this heavy, dead Naturalism.”

In this post, we’ll be looking at the material presentations by the official Catholic Church institution around this young lad, Carlo Acutis, who is soon to be presented to the universal Church for veneration of the altars. He is being breathlessly promoted by that institution as the “first saint of millennials” and the “saint of the internet”.

I have nothing whatever to say about Carlo Acutis himself, his sanctity or his involvement in the internet, or whatever other thing people think is important. For reasons I’ll explain below, however, I’m deeply sceptical of the bureaucratic process unfolding right now. If you have a devotion to him, I think that’s fine; we will be talking about him pretty much not at all.

But there are a lot of questions that are worth raising about the material aspect of his cultus, being breathlessly promoted by men in the Church who are themselves deeply suspect and are not known for either their piety, moral uprightness or a firm grasp of the nature of sacred art. I think the questions are important for our ongoing discussion of what does and does not constitute authentic spiritually-grounded sacred art, the kind that is presented by the Church officially for veneration by the faithful.

Why might an Orthodox or Byzantine Catholic person regard that statue above as idolatrous, and is that relevant for us Latins?

What’s the actual purpose of real Christian sacred art? Is it just a memorial of a person or event in this world? Or something more?

How does the mediation of the Faith through the internet - including persons presented for veneration at the altars - confuse our understanding of the Real Presence?

What is the difference between sacred and profane objects in western liturgy?

What is metaphysical Naturalism and why is it incompatible with Christian mystical theology? What does it have to do with sacred art?

What do Eastern Christians/Orthodox say about the insertion of Naturalism into Christian sacred art?

What is the role of abstraction in Christian iconography and how it is related to the expression of Christian mystical theology, as opposed to naturalism in western Christian art.

What is liturgy and liturgical art for in Christian theology?

This is an in-depth post free to all subscribers and readers. I hope you’ll join us in this exploration into these much-neglected issues of our Catholic praxis.

Please consider taking out a paid membership, so I can continue doing the work and expanding it. You can subscribe for free to get one and a half posts a week. For $9/month you also get a weekly in-depth article on this great sacred patrimony, plus extras like downloadable high res images, photos, videos and podcasts (in the works), as well as voiceovers of the articles, so you can cut back on screen time.

We are significantly further ahead in the effort to raise the percentage of paid to free subscribers than we were a month ago, from barely 2% to just over 4.2%, but this is still well below the standard on Substack for a sustainable 5-10%.

The other way you can help support the work is by signing up for a patronage through my studio blog, where you can choose for yourself the amount you contribute. Anyone contributing $9/month or more there will (obviously) receive a complimentary paid membership here.

You can also take a scroll around my online shop where you can purchase prints of my drawings and paintings and other items.

Like this drawing of St. Francis of Assisi, based on a 13th century original painting - very abstracted medieval western iconography.

Is it still the Real Presence if it’s “virtual”?

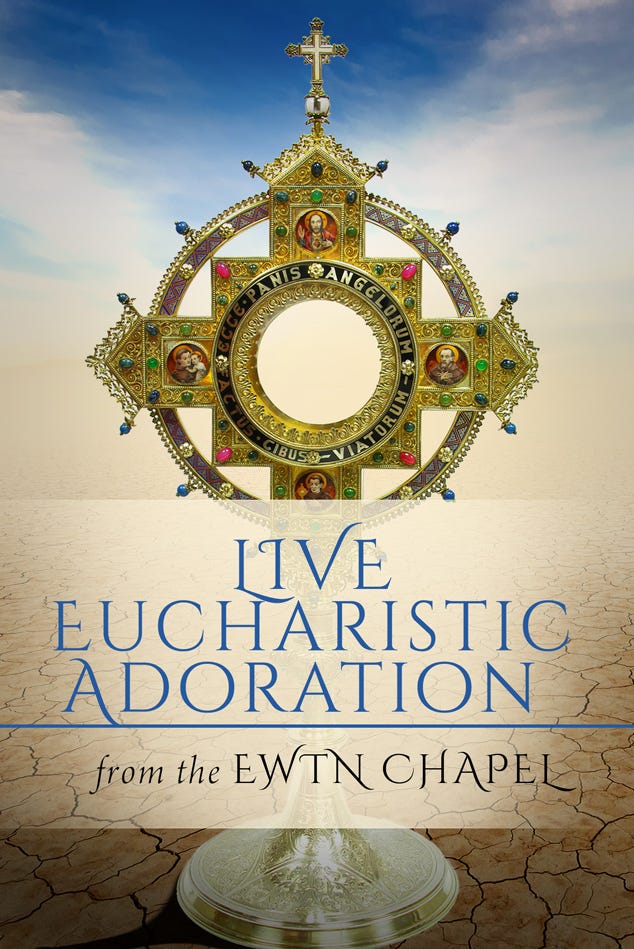

What am I really seeing when I’m looking at one of those “online” or “virtual” adoration websites or YouTube channels? Am I face to face with the living God? Or am I just watching the screen? What’s “real” about this presence?

The material output of the cultus… the… let’s call it… bureaucratic machinery surrounding the promotion of Carlo Acutis as a saint of the Catholic Church, seems to be carrying a markedly naturalistic temper, as well as the distinct aroma of the professional PR media exercise. And some of it just goes into the realm of the bizarre. It’s raising a lot of questions for me.

Why do I instinctively recoil from this image?

Maybe, it’s the Ciborium somehow… emanating…? out of a computer screen? Let’s think for a moment about what this symbolises. Are we proposing the laptop - and the internet - as a kind of Novus Ordo sacred vessel now, with the implication that the internet can be an authentic conduit for sacramental grace, like an icon?

How distorted have our minds and perceptions of reality really become from the internet taking over all aspects of life, including our spiritual lives, feeding reality to us through its distorted frame? How many people out there really think a “livestream” of adoration on their computer screen is the same thing as being in the same room as the Eucharist?

Why is there such a flaccid acceptance of the bizarre and abominable practice in some parishes of “overflow” people being sent to watch the Mass over closed circuit television in another building or in the basement, when the church is full? How many people thought watching the Mass online during Lockdowns was the same as being in the church? How many had that idea reinforced by the bishops suggesting that your sacramental obligation could be met by the Screen?

Is that true? With the bizarre metaphysical distortion of suggesting that the internet and real life - indeed, the Author and Source of life, of reality - are the same thing? Did the artist stop to wonder why the Church doesn’t allow confession over the phone? Is it really the “real presence” if it’s “virtual,” and not an actual, you know… presence? Does anyone think about this anymore? What does the word “virtual” actually mean?

Carlo Acutis, the Novus Ordo establishment and the terrible, terrible art…

The desperate insistence by the hierarchy on depicting Carlo Acutis with the focus on the technology he used seems to come out of a particular kind of Vatican PR machinery - a particular set of priorities - that people outside might not understand. There is a mania right now in the ascendant factions in the Vatican for demonstrating how up-to-date they are, particularly in the area of modern communications technologies.

This is a bureaucratic culture - almost the exclusive province of octogenarian and septuagenarian Italians and Latin Americans - who have never used a computer in their lives.1 And it is a culture that has shown itself, beyond doubt, to have entirely forgotten the actual purpose of the Catholic religion, indeed, to have aggressively rejected it.

What is the message given by this obsession in the art and publicity surrounding Carlo Acutis? What are they actually trying to show about him, and by extension about themselves? Is it Carlo Acutis’ personal holiness, his heroic sanctity? Or is it something else?

The beatification Mass conducted at the Basilica of San Francesco, Assisi, 2020.

I know next to nothing about Carlo Acutis himself, and have no judgment to make at all about his sanctity,2 though the eagerness with which he is being presented as a subject of veneration by the doddering would-be hipsters in the Vatican fills me with grave scepticism.

I’ll never dismiss the possibility that a young person of our time could reach the heights of the Transforming Union. It’s the cultus being built around him by the curial bureaucracy, especially its visual presentation, that is starting be troubling. The way he is being … well… sold. It seems to me the embodiment of all that the Novus Ordo, VaticanTwoist, New Paradigm Church loves, which can be summarised thus: "We’re cool too."

And this is VaticanTwoism in a nutshell: since the 1960s, the desire has been to be part of the Cool Kids Club of the World, and they’ve succeeded. They're with the in-crowd now, invited to all the best UN conferences, pressing their favourite cause, the Millennium Development Goals; in with Davos, the EU “project” of “ever-closer union”… the works. They’re part of the club of globalist elites, albeit junior members. So it makes sense that they’ve prioritised the canonisation of Acutis because, at least to them, it means, "We're finally cool. We’re like, cool now, right? Like the young kids. We have websites! And the pope has a Twitter account! We're cool now, right?… Right?"

What exactly is that statue pictured above and the other images supposed to tell you? What is it supposed to teach you about God, about Christ, about sanctification? Or even about Carlo Acutis? How is supposed to push you towards God? It does none of those things. All it has to say is, "See? We're not that different. We're just like you normal people. We're cool and we've got cool, young-person saints, and we don’t sweat too much all that boring holiness stuff."

But if you ask one child, what was the saintly thing about Acutis, what did he teach us, how did he love the Lord, would they know from looking? Does the art tell us? There's nothing in any of the images that indicates the love of God to a heroic degree. It's just about this world, this life, a naturalistic memorial depiction of a young boy as he appeared in this life - a commemorative statue based on a holiday snapshot.

What reason does that statue give anyone to believe in the heroic sanctity of Carlo Acutis? What justice does it do him in his own priorities in his lifetime, focused on the Eucharist I’m told, to emphasise only his technological abilities (quite ordinary by current standards) and make him a literal poster-boy of the Vatican’s current obsession with technocratic modernness - with, in other words, this world?

Naturalism and idolatry: we worship the Creator, not creation

We have a philosophically corrupted visual culture in the modern western Church, and have to find a way to bring it back from this heavy, dead Naturalism. I wondered what an Orthodox or Byzantine Catholic Christian might think of that statue and these other depictions. Mightn’t they regard such an aggressively naturalistic or materially “realistic,” secularised statue of a person with suspicion, potentially even viewing it as idolatrous?

The history of Christian sacred art is not an untroubled one, and though we have mostly forgotten, in the East the memories are still alive and the implications of getting it wrong taken seriously. The Iconoclastic Crisis was triggered by accusations of idolatry levelled at Christians by Jews and the new Islamic religion, and led to a long period of violent persecution and upheaval. Blood was shed over the correct understanding of sacred images. And those same accusations of idolatry - perhaps without the threat of violence behind them - are commonly made today by Protestants. What are we doing to correct that impression by the material output of the western Church?

So, what does all that mean for us now? Why, exactly, is excessive Naturalism considered in the east to be so poisonous to the purpose of Christian sacred art? And why is the abstraction we see in Byzantine art, so odd to western visual sensibilities, considered indispensable for conveying the meaning of an icon?

Abstraction, illusionism and the Real

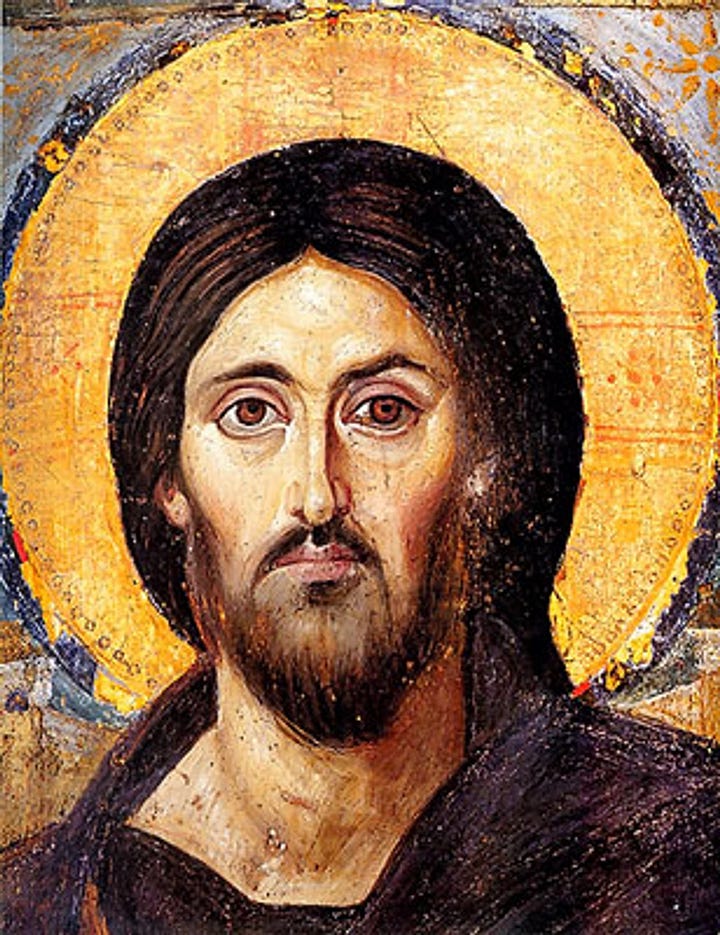

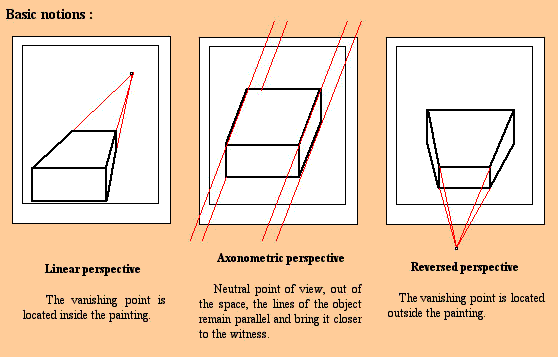

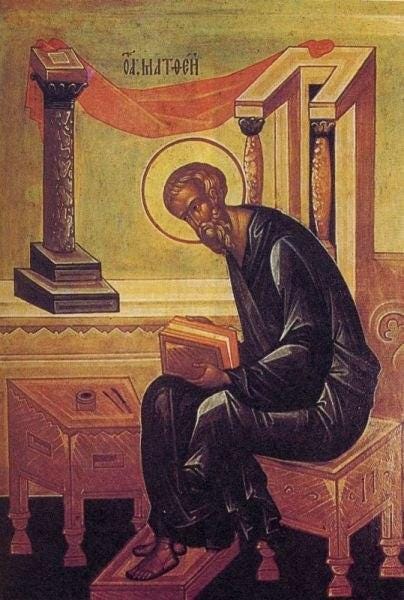

In the east, iconography uses symbolic abstraction over “illusionistic” naturalism. This means that the figures in icons are depicted with certain stylized and mathematically standardised features3 - elongated figure proportions, serene expressions, and a lack of linear, “3D” perspective - to convey their spiritual rather than physical reality.

The key to understanding is to remember that the physical, material appearance of objects in space is only a tiny fraction of the reality, and the least important part, being conveyed in an icon. Perceptions are, to start with, always deceptive, but more importantly, sacred art is primarily about depicting the complete reality of the person, including the invisible realities, something mere materialist naturalism is incapable of, no matter how skilled its maker.

In 787, the Second Council of Nicaea4 affirmed the veneration of icons, distinguishing it from the worship due to God alone, and from the idolatry of the pagans. It was a result of the conflict that the art of Christian Byzantium embraced abstraction and geometrically reproducible, idealised human forms, and in an effort to scrupulously avoid idolatry, the worship of mere creation instead of the Creator.

It was in this period that the crucial distinction was established between veneration (proskynesis or dulia) and worship (latreia). Icons were accepted because they were seen as windows or portals to the divine, not as objects of worship themselves. At the same time, because of their function, they were, and are, regarded as sacred objects, similar to the veneration western Christians give to religious relics and for the same reason; the icon is seen as a conduit from heaven to earth. They were not mere pictures, any more than altar vessels are mere dishes.

Icons, and all the Christian art forms that followed the Byzantine style are intentionally symbolic, abstract and idealised. But this is not the abstraction of meaninglessness, nor is it the material world of philosophical Materialism. When we talk about abstraction vs. naturalism in Byzantine sacred art, we have to understand what the terms mean. We aren’t talking about abstraction as it’s used in modern secular art, intended to distort or nihilistically refute material reality, as we see with the splodges and splatters of Jackson Pollock or the Cubism of Picasso.

It could be said that “abstraction” has been legitimized as a crucial pictorial component in the realization of the icon’s liturgical function. However, let us not forget, there is also naturalism in the icon. The icon embraces both abstraction and naturalism.

Hieromonk Silouan Justiniano, iconographer

The aesthetic principles of iconography are deeply symbolic, with every element, Colour, composition, and style, carrying a particular meaning. For instance, gold backgrounds signify the divine light, the eternity of heaven, while the use of so called “reverse” or Byzantine perspective invites the viewer into the sacred space.

Icons are intended to be tools for mystical contemplation and prayer, to create a connection with transcendent realities that include and elevate the material. The abstract style directs the viewer’s mind and heart away from the mundane, the material, and towards the divine, the unseeable. And that includes the restrictions of time. Biblical scenes in iconography are not depicted as if they are a snapshot taken by a time traveller, and often many events that happen sequentially in the Bible are depicted all at once in the same image.

Abstraction in icons helps to convey the timeless and spaceless nature of the divine. Unlike naturalistic art, which is bound by the conventions of perspective and temporal realism, iconography transcends these limitations. This allows for a more direct engagement with the eternal truths of the Christian faith.

Holy Icons and Metaphysics: it’s all about the Incarnation

The whole earth is a living icon of the face of God. ... I do not worship matter. I worship the Creator of matter who became matter for my sake, who willed to take His abode in matter, who worked out my salvation through matter. Never will I cease honoring the matter which wrought my salvation! I honor it, but not as God. Because of this I salute all remaining matter with reverence, because God has filled it with his grace and power. Through it my salvation has come to me.

St. John of Damascus, answering the Iconoclasts

Metaphysical Naturalism and Christian mystical theology are fundamentally incompatible due to their opposing views on the nature of reality, the existence of the supernatural, and the role of divine experience. The key to grasping this crucial distinction is the doctrine of the Incarnation, the most foundational of the Church’s Christological doctrines. In the incarnate Christ, as St. John of Damascus said, the invisible is made visible.

Metaphysical naturalism: everything that exists is part of the natural world. All phenomena can be explained by natural causes and laws without resorting to supernatural explanations. The natural world is all there is; there is no realm beyond the physical. All knowledge is gained through empirical observation and scientific methods. “Transcendence” or spiritual realities are therefore meaningless and unreal.

Christian mystical theology, on the other hand, holds that reality includes both the physical and the spiritual and that these things, while not the same, are unbreakably linked. It acknowledges the existence of a transcendent, divine realm that interacts with and underpins the natural world. And in the Incarnation of Christ those two realms became intertwined and indivisibly, permanently united.

Christian mystical theology emphasizes the possibility of direct, personal experience with God and proposes that this experience will change a person into a different kind of being, and this is the meaning of sanctification. These experiences are often channelled through material things, like icons and the material aspects of the sacramental life, making the transcendent perceptible to human senses.

In the eastern Christian liturgy, because of their ability to act as a kind of bridge between mystical and material realities, icons play a specific and integral role in worship and, as an extension of liturgy,5 in personal devotion. And that liturgical devotion is centred on icons because it is understood that Jesus Christ is the ultimate, living “icon of the invisible God” (Colossians 1:15). The Second Council of Nicaea affirmed that because God became visible in the incarnate Christ, it has become possible and correct to create images that depict Him and use them as an integral part of divine worship, personal and public.

But more than that, the Incarnation sanctifies the entirety of the material world, showing that physical matter can be a means through which God reveals Himself.

I’m not making this up: they send each other telegrams inside the Vatican. Yes, like Bertie Wooster.

Though it must be said that the bar is set so low in our times that it seems almost none of us know what actual heroic sanctity looks like.

To which the pope in Rome sent delegates, though he did not attend himself. The political situation of Rome at this time was a distraction from what was going on in Constantinople, including the pressures of the very aggressive new Islamic religion. The papacy’s distance from the paroxysms of Iconoclasm was the first step toward the later Great Schism.

The de-linking of formal liturgical worship and private devotion that has become such a defining habit of western Christianity, is impossible in the eastern rites. This divorce of liturgy and devotion has allowed all manner of non-Christian practices - New Age, etc - to creep into the life of the Church.

While Blessed Carlo is in my mind, in his writings and actions heroic, the common art depicting him (as in the two images you presented) are not worthy or even able to be venerated.

We have commissioned an ikon of him by a respected ikonographer, who knows the “canons” of ikonography and will not depict him as a portrait or as a secular figure.

Wonderful post, and so well articulated. I, too find, the images presented as banal and totally lacking in an understanding of proper use of art in bringing the faithful to a deeper relationship with God. (The images of Acutis smack of something called the “uncanny valley” that happens in producing animated images of human beings. It’s easy to design cartoon or video game characters that are somewhat abstracted. When animators try to portray human beings naturalistically, something always seems “off”. The disconnect between a human-like appearance and the negative emotional response it provokes is the uncanny valley.) There are too many poorly formed artists commissioned to pump out kitsch “religious” art to satisfy the desires of equally unformed patrons. Even highly-trained naturalist artists are producing ever-larger altar pieces that do not belong in a liturgical setting. Your efforts at educating people about the proper creation and production of truly sacred art is very important. Thank you!