A few months ago on my Facebook page, Hilary White; Sacred Art, I floated the idea of a home schooling programme or curriculum to teach children and their parents some of the fundamentals of Christian Sacred Art. The response was so positive that I’ve been reading and taking notes since then to develop an outline. I have a nice bound notebook that I’m using to just gather into a big pile all the ideas about what people need to know to increase their basic sacred art literacy. In pencil.

I’m ten pages into the outline and we’ve only gone from pre-Christian Egypt to French Romanesque, and ideas for articles and separate modules have been popping up like dandelions along the way.

Just doing a simple timeline isn’t as simple as one might think. If you take Christianity itself as the road you quickly realise that Christian Art History takes as many side roads and twists and turns as Christianity itself did. There are certainly general movements, but the timeline starts branching immediately, and by the 6th century looks a lot more like a tree on its side.

What all that means is that once I start writing about it - which I guess I’m doing today - I’ll keep having something to do well into my 90s. Good thing I type fast.

I’ve been puzzling somewhat about what to do with this Substack blog. I don’t want to write about political things anymore. So I think I’ll mostly write about art.

The modern world is wrong about art

On pretty much every single point.

The graph below is what Modernians - secular modern people in what we must now call “western” nations, who maybe learned a little bit about art history in school think about the history of art. It’s really quite a good illustration of the priorities, assumptions and prejudices of academics, and what they think of the importance of Christian sacred art, and by extension Christian civilisation in general.

Western academia holds as self-evident that for every useful purpose, art didn’t start until a thousand years after Christ. And even then everything produced was hijacked by the Church, which was the only power around that could afford to commission works. This was the dark state of affairs until the blessed dawning of the Renaissance freed the world from the darkness of oppression and superstition.

Christian civilisation gets a brief mention in passing for the first two categories; the fact that it spans the greatest single section of the timeline - over 600 years - is apparently irrelevant. It was called - and dismissed as - “Primitivism” by academic art scholars for a very long time for a very good reason.

I don’t know how they convince themselves, let alone anyone else, that the first 1500 years of Western art is completely irrelevant. Particularly since the largest section of this list on the vertical axis is taken up with the nonsense and chaos of the 19th and 20th centuries - the worst centuries in human history.

Byzantine doesn’t count

I do know, however, that the complete absence of even a mention of Eastern Christian art - what we incorrectly lump together as “Byzantine” - that flourished everywhere Christianity grew for 1000 years, is more than a little revealing of the value of contemporary “academic” discourse.

If art seems irrelevant, it’s because we’ve made it so.

Art is correctly understood as the reflection and expression of a given culture; whatever a culture has to say it will say it with art. It expresses not only the culture’s interests and priorities, but its way of thinking, its self-understanding and cosmological outlook. So if your art is irrelevant and stupid what more do we need to know about the culture it comes from?

Art is simply those things that human beings do to communicate cultural meaning. Only a modern secular man thinks “Art” cannot be defined. But this is because he has embraced the un-embraceable1, and tried to convince himself that definitions aren’t a thing, that reality itself is personal, subjective and conditional on feelings and preferences. But the personal and subjective cannot be the basis of culture.

A reality that is not the same for the whole population, but changes fundamentally from person to person, cannot serve as the foundation of anything. It automatically atomises the society that tries to embrace it. And anyone trying to make art from this anti-culture will necessarily be speaking without language.

A society that refuses to have a culture, that leaves the determination of culture - of reality itself - up to the whims and preferences of individuals, cannot create art. And this is why the “art” that is created now is of interest to no one but the insular and self-referential group of people buying, selling and promoting it. The officially recognised - and often state-sponsored - art world is an island of people each talking nonsense gibberish to each other. It is best left to itself.

So, we’re just going to ignore it

As I work on my outline and timeline of Christian Sacred Art, for all its historical complexity, depth and nuance of theological and spiritual meaning, it’s cultural influence, I look at the timeline in that graph and am relieved about one thing at least; I won’t have to bother my head much about anything that happened after about 1700.

And reading and writing about the art of Christianity between 300 AD and 1650 certainly leaves me plenty to think about.

Here’s a taste.

What is Byzantine art?

Pre-Christian origins in Egypt, Greece and Hellenic Judaism

Christianity dawns: Christian (Coptic) Egypt, Africa, Syria, Greece and Rome under persecution

Alexandria and Sinai - the monastic desert cities and first true icons

Emancipation and Imperial sponsorship

Constantine moves the Empire East

Byzantine art of Italy

The “Barbarian” Invasions: Germanic, Lombard and northern European influences

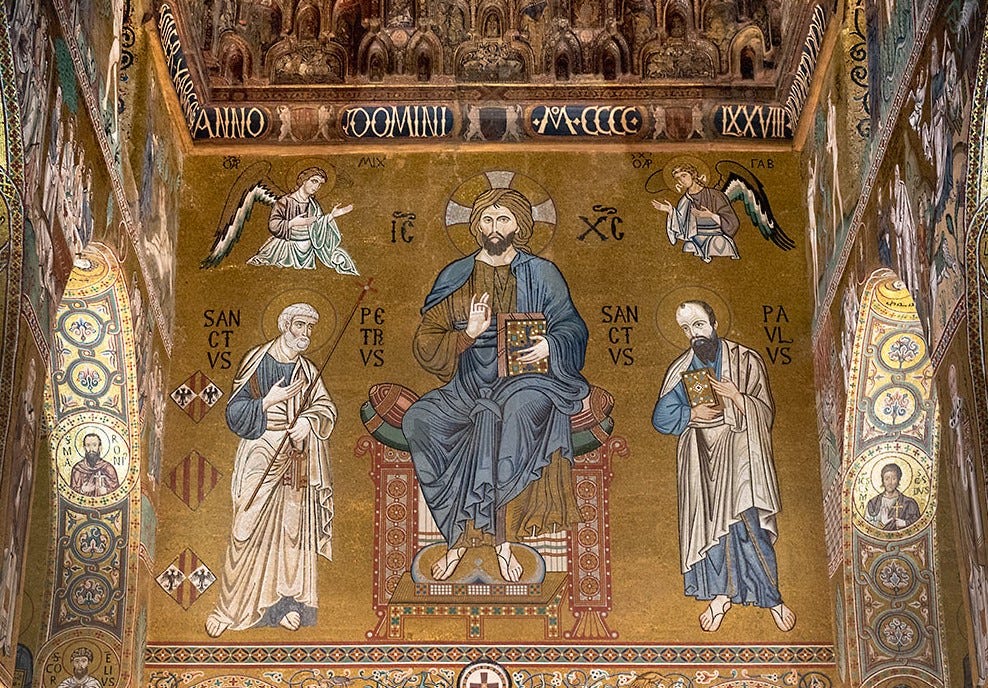

Norman conquest of Sicily: the art of the Northmen in the south

Islamic influences in the Levant, the Balkans, Christian Armenia and southern Italy

Christianity’s art in Russia

Forms in Iconography: wall frescos, mosaic, panel icons

The liturgical architectural setting: icons in churches

The splitting of the empire: Iconoclasm, the Filioque and the Great Schism

Charlemagne, the Carolingian Renaissance and the invention of “Europe”

Codex books and Carolingian Miniscule; Ottonian and Carolingian manuscript art and the first pan-European writing system

Insular or Hiberno-Saxon - the art of the monastic North

Insular script: the books of Kells and Durrow and the Lindisfarne Gospels

Irish and Hiberno-Saxon missionaries carry their “Celtic” artforms to the continent

Stone carving of the early Middle Ages

The Crusader cities of the Holy Land

Romanesque; the Nazareth column capitals

Articles:

Nazareth Column Capitals: French Romanesque stone carving and the crusades

The Palatine Chapel: the synthesis of Norman, Byzantine and Islamic art in one building

Spot the style: How to tell Byzantine, Romanesque and Gothic at a glance.

What’s the difference? Not all art about Christian subjects is sacred art.

etc…

I guess that’s about five to ten years worth of work, and we’ve only got as far as about AD 1100. So, that’s plenty to be getting on with, I think…

It’s your civilisation whether you like it or not

The most interesting course I took in high school was called Western Civilisation 12. It was based on the now-classic series of documentaries made in the late 1960s by Sir Kenneth Clarke, called “Civilisation”. The whole series is available for free on YouTube, and was one of the most calming of the distractions I indulged while getting and recovering from cancer treatments some years ago.

The course was necessarily focused a great deal on the doings of the Christian church throughout its long history, in both its Latin and Byzantine branches. Our teacher, a man whose intelligence and wit - not to mention his PhD in art history - made me wonder what he was doing teaching high school, told us that he had once had an angry letter from a parent, appalled that a public school was “teaching Christian theology”.

I don’t remember what he said the parent did in response to his message that whether she liked it or not, the history of Western Civilisation was exactly the same as the history of Christianity, and if she didn’t like it she was free to withdraw her child from the school. Those were different times.

~

Thanks for reading to the bottom. I hope you all will enjoy some mental and spiritual refreshment talking about art, instead of All That \Awful Stuff. Click on my Ko-Fi page, Hilary White: Sacred Art if you would like to help support my work and see my paintings.

We’ll talk later about the Logical Principle of Non-Contradiction too. Suffice for now to offer this handy trick: “If reality is entirely subjective and dependent upon personal preference, why doesn’t my preference for reality being objective count?”

Excellent move away from the latest current thing(s). I like your choice of the Palatine in Palmero - the culture of Norman Sicily is magnificent in its artistic expression. That move from Warlord-Baron to Byzantine-Norman King is brilliantly expressed in the mosaics and architecture. I look forward to what follows!

This is great. I look forward to more from you on sacred art.-Jack