The Renaissance erased our memories

We talked the other day about the surprising fact that our most revered period in western art, the Italian Renaissance, is not that well thought of among Eastern Christians. To people of the Eastern Orthodox or Byzantine Catholic churches, this is not sacred art. It is secular art with a sacred subject:

No one would dispute that this is a magnificent work of art, the very pinnacle of craft. But a Byzantine (eastern) Christian would insist that it can’t be called “sacred art” and has no place in a church.

The Christian East regards this great flowering of realism in art as a regression into straight-up paganism. They call its realism, “naturalism,” in the theological sense, inasmuch as it concerns itself not with ultimate, heavenly realities that must be depicted in symbolic visual language - with a very specific vocabulary of colours and forms - but with the things of mere material, physical, natural world. The subjects may be from the bible or lives of the saints, but the style in which they are painted makes them secular. This is art, they hold, that is earthly, this-worldly, holding higher, spiritual realities in contempt. The corruption of Renaissance naturalism has caused western Christianity to forget that ancient sacred visual language.

Sacred art in its original universal (“catholic”) intention - in the early centuries there was no distinction made between the Greek East and the Latin West, all Christian art was “Byzantine1” or iconographic - was to erase the distance between heaven and earth; to bring heaven into the room with you, and therefore sacralise the space in which the art was shown. This means the painting itself was a sacred object, and not merely a thing representing an event or person from the past.

The Orthodox and Eastern Catholics “venerate” icons as sacred objects, in a way similar to the way Latin Catholics venerate sacred relics - as a holy thing itself. They might say that a painting like the Raphael above would go nicely in a non-liturgical setting and even that it should be greatly admired for its beauty and mastery; but it should never be used in a church for liturgical worship.

These ideas are often shocking to Latin Christians (or post-Christians of the Latin west) who have learned to regard the works of the Italian Renaissance with an almost atavistic sense of awe. We think ourselves in the presence of something higher and greater standing in front of these works in museums, whatever their subject. At least, as long as they are by a name we recognise as “important”.2

In the west, we have more or less abandoned any notion of “canons” or rules for creating legitimate sacred art - the kind that should be placed above an altar in a church. And have consequently replaced the ancient symbolic language of sacred art with a kind of secular veneration of “looking real”. Whether that’s a good or bad thing is a discussion for another day. For now I’d like to talk about how and when.

What ideas did we get from the Italian Renaissance that so fundamentally altered our assumptions about what sacred art is and what it is for?

These aren’t angels; they’re “putti”

One of the most noticeable features of the transition from Gothic or medieval sacred art to the Renaissance is the odd appearance of the angels. Gone are the magnificent, and often terrifying, heavenly messengers with enormous wings, flowing robes and stern expressions rescuing foolish men from demons, whether they want to be rescued or not.

We moved from these to the more softened, though still regal and impressive angels of the later middle ages, the Italian Trecento and Quattrocento:

And then on to the close of this period with the “Proto-Renaissance” of Fra Angelico:

Then we hit the 1400s and suddenly we’re seeing these fat flying infants all over everything instead:

A cherub is an angel of a high rank, that directly attends to the throne of God, described in the Bible as having four faces, one of a human, one of a lion, one of an ox, and one of an eagle with three sets of wings.

We started getting the idea that angels looked like pudgy infants from the revival by Renaissance painters of the Romano-Greek (ie: pagan) beings related to Eros or Cupid, a god of sexual love, from which we get the word “cupidity” for undue interest in sensual pleasure, especially sexual, or avarice. (Not very heavenly.) The Italian word “Putti” (pl.) comes from the Latin word putus, meaning "boy" or "child".

Why? We don’t really know. The idea to bring back putti and call them angels and start putting them into paintings intended for churches just seems to have popped into the head of the Florentine sculptor Donatello and everyone else picked it up.

The difference in intention between the medieval painters and the famous Renaissance A-listers is described by the Galleria Bazzanti :

In the Middle Ages Cupid lost its classical form, Christian art and literature distanced themselves from the influence of the Hellenistic mystery religions of early Christianity which had allowed the cherubs to appear, in their classical form, in the vintages of the catacombs and the sarcophagus of Constantine. The erotic image of Cupid becomes unacceptable to the church, which begins to portray him as an evil emanation, his appearance loses joy and becomes sinister: no longer a child putto, in the fourteenth century he transforms into a diabolical being with animal paws ; we see him in this guise in Giotto's fresco in the Basilica of Assisi (1325) in which the inscription with his name "Amor" appears.

Giotto was a Christian who remembered that “all the gods of the Gentiles are devils: but the Lord made the heavens.” Between Giotto (d.1337) and Donatello (b.1386) a scant 50 years lies.

.

Christian subjects, but secular art

Quite simply, the Renaissance was not a Christian art movement; it was a movement of secularisation. Its main patrons were still Christians, so the works depicted (mostly) Christian subjects. The Renaissance rebirth was not of long-lost painting techniques, mathematical perspective or anatomy; but of the values and interests of the pre-Christian classical world. This movement was a deliberate shedding of the canons of the great Italian Gothic and Italo-Byzantine Christian sacred art that had prevailed on the peninsula for centuries, and had reached extraordinary heights.

In his essay, “Orthodox iconography versus Renaissance art” Dr. Stephane Rene explains how the movement toward naturalism - the attempt to create an illusion of nature - opposes the Christian traditions of (liturgical) sacred art:

Being mostly secular and free-thinking individuals, Renaissance artists were as much at home painting pagan subjects as Christian ones and sometimes enjoyed mixing the two in more or less ambiguous allegories…

Iconography on the other hand, does not attempt to faithfully imitate the carnal body of flesh and blood which is corruptible, but focuses on the transfigured incorruptible body, which it renders according to specific symbolic conventions rather than the imitation of physical reality.

In addition to this fascination for realism and the natural world, the introduction of receding perspective in painting engendered a new kind of art, fundamentally different, and at the opposite pole of iconography. This radically changed the previously sacred and symbolic character of Western Christian art. Among other things, perspective allowed for the development of trompe l’oeil, which in French means literally ‘to fool the eye’, or in other words to create an optical illusion of three dimensionality…

This shift in Italy from the traditional pan-Christian conventions in depicting sacred, heavenly realities in a symbolic way to mere earthly naturalism, greatly contributed ultimately to the decline of Christianity as a sanctifying force in the west, Dr. Rene writes:

It is important to realise that although it manifested in the midst of Christian Europe, the Renaissance was not based on Christian foundations and ideals, but on the rediscovery of Classical Greek and Roman thought, which help shift the Christian West from a theocentric or more accurately, a Christo-centric cosmology to an anthropocentric world view with reason and science as its new gods and humanism as its new theology. Hence the ideas that took root during the Renaissance brought forth humanist thought, which eventually morphed into the so-called Enlightenment in the 18th century, giving rise to the empirical scientific/industrial/technological model still prevailing today.

A quick, inaccurate history of art

We take it for granted that “art” has experienced a progression from bad to good, from primitive, naive and silly to realistic, sublime and wonderful. This is an idea thoroughly sold by academic art historians3 (who referred for a long time to Gothic painting as “primitivism” … and to Byzantine art not at all.) But this view of the history of western sacred art is itself a product of Renaissance propaganda, eagerly picked up and run with by Protestant and post-Protestant academics interested in downplaying Christian art as unimportant and Renaissance neo-paganism as a liberation from “Church control.”

I was taught a very Euro-centric and very, very secular version of art history in my courses in university. In this model, art developed in the north and west Mediterranean areas from primitive styles of early Greek societies - late Neolithic and early Bronze Ages.

These were things like the Cycladic figures and the Maltese fat ladies ("corpulent votive figures"), developed in these nice warm climates where people had time on their hands. These slowly developed into more naturalistic styles through the Archaic period and on into "Classical Greece," when we got the Parthenon friezes.

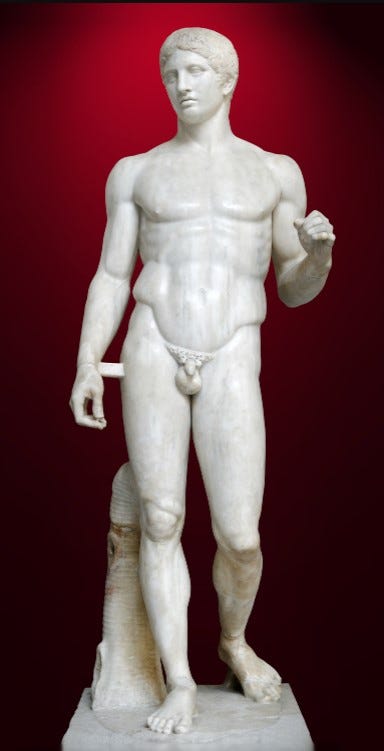

It was all getting more glorious and naturalistic and beautiful...

Getting more relaxed and contrapposto…

Then the whole business was picked up by the Romans, who were big into naturalism, aqueducts, roads, bridges and realistic portrait busts.

Everything was going swimmingly until "Rome fell to the Barbarians" (darn those guys and their primitive art!) and finally Christianity took over and made everything stupid again and we had to climb that hill all over from the bottom.

We fell back into our primitivist ways because we forgot how to make indoor plumbing and roads and art, and produced a lot of these weird, stiff, unrealistic figures, mostly in frescoes and mosaics, to entertain the masses while the priest did his unenlightened mumbo-jumbo at the altar with his back to the people. This was The Dark Ages where people were ignorant and illiterate and superstitious for a thousand years or so and nothing good happened.

And then BAM! Leonardo da Vinci the Genius Superhero invented Aristotle the Renaissance, perspective, sfumato and wooden helicopters and then everyone learned to read and joined the middle class and then Protestantism and then the New World and the Enlightenment and the French Revolution and democracy and freedom and equality, and we were finally saved forever by our own cleverness from our dark ignorant, credulous peasant past full of priests, spooky chanting and bad art.

I think this is probably the general picture most people have about the development of western art.

Turns out it's kind of wrong on every point.

…

Stay tuned for Part 3 of Lies the Renaissance told you.

Thanks for reading to the end. If you would like to see some of my “real” work, my painting, you can click on my Ko-Fi page, Hilary White; Sacred Art, here, where you can also drop a few coins in the tip jar if you enjoyed this. Right now painting and donations from supporters and patrons are my sole source of income. If you sign up to be a monthly patron, you can join my private patrons-only chat group on Signal.

You can also follow me at Hilary White: Sacred Art on Facebook and see a little hint of the Old Hilary White; journalist being cranky on Twitter too. Many thanks to all who have contributed to make it possible to keep working - the “struggling artist” thing doesn’t last forever, but it is a struggle for a while. Stay tuned.

We’re going to have to keep using the term for now to describe the earlier, symbolism-oriented forms of art, since to the western mind it is a catch-all and helps orient us. But later we’ll get into some of the distinctions. There are forms of traditional Christian art that fit in our minds into this category that have nothing whatever to do with Byzantium. cf. Coptic and Ethiopian iconography.

The cult of adulation - not veneration - of these paintings is one of the first instances of what was later to become the secular “cult of celebrity” that has become such a feature of life in the modern period. We’ll talk more about this later.

Let’s face it; Anglicans.

Thank you so much for this series, and all the other essays regarding the Renaissance. We moved to Italy 18 months ago, (la familia de mio marito e Siciliana), and lived in Rome for five months, (not nearly long enough!). We were painfully confronted by our dismal grasp of the history and art of Europe. Our education was U.S. centric, (where, in Los Angeles, some of the buildings are more than twenty years old!). In any case, we are curating our developing understanding and access to knowledge such as yours is invaluable! We had recently been introduced to Cosimo de' Medici and this was a great build on that. Maybe we can have a coffee in Roma some day! (We try to go often!).

I'm more and more sympathetic to your argument. But to play devil's advocate, couldn't one argue that the Renaissance style derives, in some ways, from the Aristotelianism (and its more positive view of the flesh vs Platonism) that began to make its way onto the scene in the 12/13C? This brings in its train (arguably) a greater focus on the humanity of Christ. We see statues and crucifixes get more common around this time too. So perhaps Renaissance 'naturalism' is part of this trend.

On another note, I remember hearing Alan Fimister (on a podcast somewhere) argue that the Renaissance/classical style of architecture involved a great loss of confidence, and Faith, compared to the gothic style. Instead of Christians doing their own thing, they just copied the ancients. The first 'pastiche', as it were. This seems to backup what you're writing above.

And on yet another note, I thought one view of the Renaissance was that it resulted (in part) from the fall of Constantinople, and the resulting exodus from the East benefiting Italy with its culture. This would suggest that the East and West moved <i>closer</i> at this point, not further, as you're writing above.

So many currents to trace. But for sure, things were going seriously wrong by the Baroque era... there's an kind of arrogance about its art.