Part 2 of our series “Know your sacred art terms: Romanesque”

A few days ago we talked about one of the “forgotten” forms of Christian sacred art, called Romanesque (~AD 1000 - 1200). We looked at some of the typical features of Romanesque architecture, particularly in the context of its arrival in England from the continent with William the Conqueror. This solid stone construction, with enormous monumental forms in columns and rounded arches were a study in architectural political messaging: the Normans are here to stay, Saxons; better get used to it.

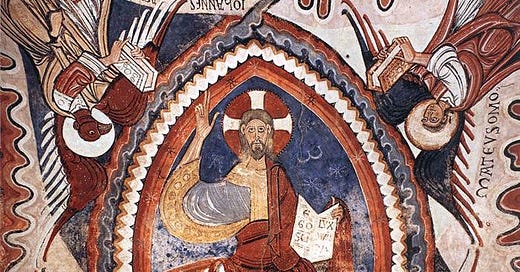

Walk into one of the few surviving churches decorated in this way and you understand it immediately; this is not Christianity safely away over there, up above the altar. It’s not God up there and far away and not very relevant. This is the entire heavenly court, all of Salvation History crowded into the room with you and looking straight at you. These aren’t images in a movie to be gazed at “reverently” from a safe distance; this is “full immersion” Christianity at its height.

Historical context

Romanesque art has sometimes been described, loosely, as “Western Byzantine” since it is mainly found in the early 2nd millennium in Western Europe and was influenced by northern European, “Barbarian,” artistic forms not found in the increasingly politically and culturally remote Eastern Empire under Constantinople. By the opening of the “Romanesque period” - 1000AD - the hopes of a revival of the political reality of a new Western Roman Empire, that had blossomed briefly under Charlemagne, had died. But the notion of a pan-national European western Christendom, a united western Christian culture, endured and grew as more European nations converted and Christianised. Carolingian art and architecture, influenced itself by Roman forms, contributed to the later development of Romanesque forms.

Romanesque painting: not just triumph but exuberance

Today I thought we’d look at some of the painting of this genre and at how it sends a similar, triumphal message. The decorative arts of the Romanesque also conveyed this idea of a pan-European, Western Christian Empire, but it also conveyed an exuberance, energy and positivity, a culture at ease with its moral status and confident it was doing the will of God.

Here we find a passion and enthusiasm not for mere conquest and dominance by a ruling class, but for bringing the realities of salvation to everyone of all positions in life, mainly through the missionary mediation of the monastic life1. This was the high point of early medieval monasticism, mostly conveyed through the Benedictine life that were major purveyors of the Romanesque style throughout Europe. Here was a Christianity that was literally going out to the peripheries in search of souls for Christ.

But we fail to really grasp the power of this art form until we understand its influence on the central experience, the reason these churches were built: the liturgy. The buildings themselves only tell us half the story. It’s what’s inside that tells the rest.

Romanesque stylisation: formalist and spiritual, not “primitive”

To modern sensibilities, trained for generations on the Post-Renaissance norms of naturalistic illusionism2 - “it’s only good if it looks real” - these figures might seem at first to earn the label “primitive”. But that would be a mischaracterisation, and would miss the message entirely. Since about 1500 we western Christians have come to think of sacred images very differently from the way our spiritual ancestors did.

We regard the image itself as an isolated “work of art” - intended to be framed and looked at as a discrete object, either above an altar or in a museum, and judged according to a set of extrinsic aesthetic standards. And those standards are necessarily humanistic; we “relate to” a work of naturalistic illusionism because it depicts the heavenly world as being very much like our own and its inhabitants as being much like ourselves, indeed, “based on” us in all appearance.

In every Renaissance Annunciation we are encouraged to imagine ourselves in the room with the Virgin, as observers, perhaps helping her spin some wool, when the angel arrives. It is “relevant” to us because it is humanistic, and therefore not terribly likely to lift us out of our preconceptions and this-worldliness.

Obviously there are similarities and both follow conventions for depicting angels, and a historical thread can be drawn between these two images, but it is easy to see that a radical alteration in the conceptual framework has happened somewhere along the way. One big difference is that we know the name of the painter of the early Renaissance version. By 1500 we were fully engaged in the cultural concept of the “artist”, and the road was paved for our current-day cult of celebrity. These two images were not intended to be taken in by the viewer in the same way and for the same reasons.

This was not at all how sacred art was used in the first millennium of Christian culture. We are working from this bias when we look for Romanesque images in books or online. We pick out this or that figure of an angel, Christ or the saints and examine it by itself. This lifting of the individual images out of their larger ecclesiastical, liturgical context is to misunderstand the Christian culture of our ancestors, for whom these images were taken as part of a great cultural whole in which they were completely immersed in every aspect of their lives.

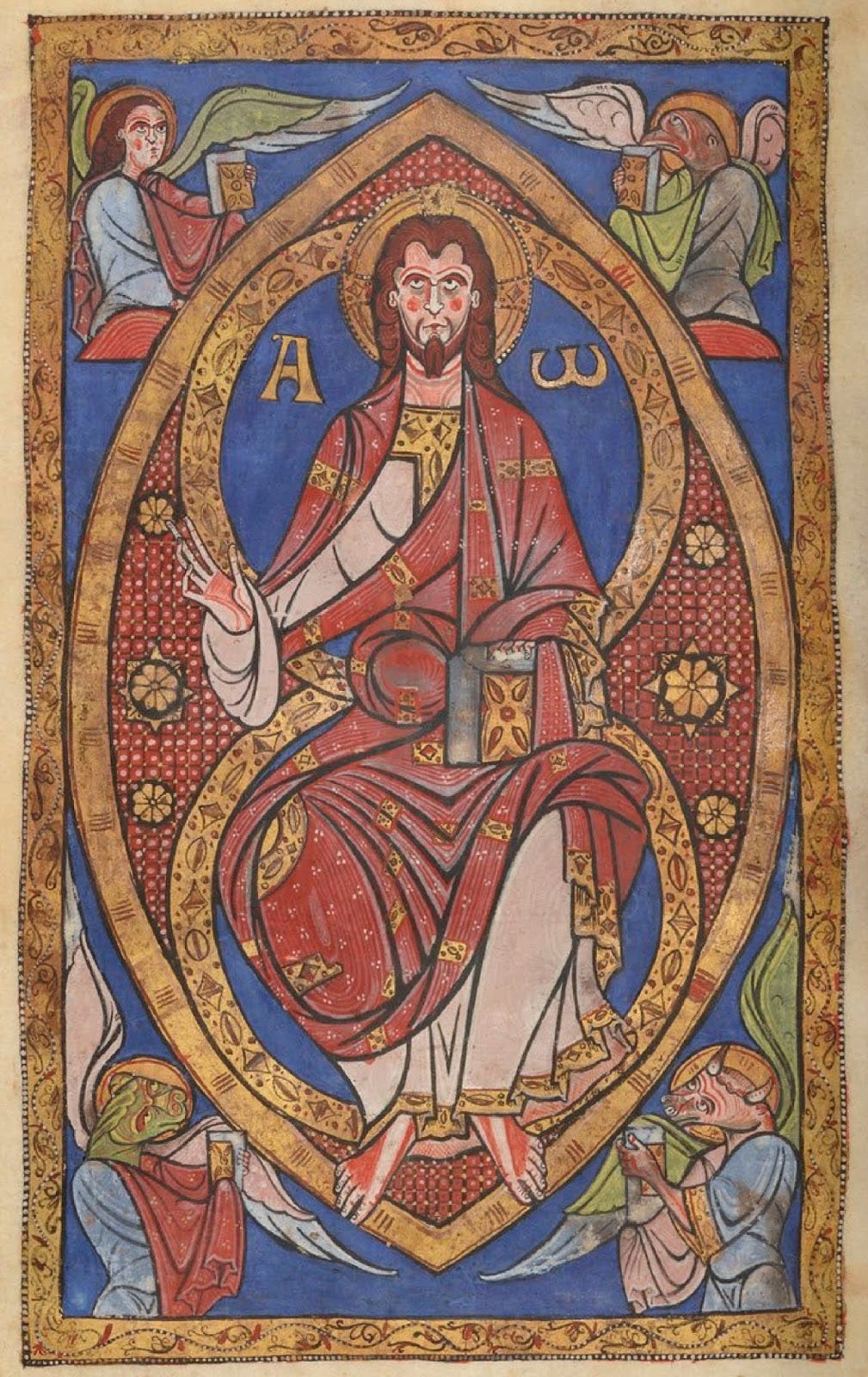

The wall of Romanesque figures depicted above - try to imagine an entire stone church covered in it floor to ceiling - does not allow us an instant of comfortable egoism. Romanesque art, especially seen in its liturgical context, makes it clear that heaven is coming for you.

Why does it look like that?

Romanesque painting is characterized by

boldly defined blocks of colours, not blended or mixed

stylized, linear, geometrical and symbolic, not naturalistic, figures

flat, two-dimensional perspective

strong, bold outlines

drapery is heavily stylised and formalised, often using the “damp fold” style, where folds of cloth are rendered linearly, and appear to cling to and outline the body’s limbs.

It’s mainly found in the form of wall frescoes in churches and as illustrations in manuscripts3.

The Benedictines were particularly influential in the development of Romanesque art, being responsible for the construction of many of the most important Romanesque churches in Europe, including the Abbey of Cluny in France and the Cathedral of Speyer in Germany. And of course because of their habit of copying and illuminating books.

Popular subjects of Romanesque painting include:

Christ in Majesty: A depiction of Christ seated on a throne, surrounded by angels and saints.

The Last Judgment: A scene depicting the final judgment of humanity, with the saved being separated from the damned.

Scenes from the life of Christ: Paintings depicting events from the life of Christ, such as the Nativity, the Crucifixion, and the Resurrection.

Old Testament scenes: Paintings depicting scenes from the Old Testament, such as the Creation of Adam and Eve, the story of Noah's Ark, and the Exodus from Egypt.

Archetypal or allegorical themes: stylised depictions of theological or mystical concepts from the text, writings of saints and mystics or scriptural commentaries.

Shop news

I wanted to take a moment to update readers on my Hilary White; Sacred Art shop. I’ve been struggling with the technical details of opening a proper Shopify store, and brother, this ain’t my area of speciality. It’s been a fight of two weeks, and I’ve only got as far as the Christmas things. Fine art prints have had to wait until I could find the right printer-shippers.

BUT! I’m almost there, and expect to be opening this week. Stay tuned. I will definitely be sending out an extra email when the moment comes.

If you’d like to support my work by donating, the Ko-Fi page is still up and working:

Many thanks,

HJMW

We must keep in mind that in the first few centuries after Christianity’s emancipation it was monasticism that was the dominant force for evangelisation, not what we would recognise today as “parish life” based in urban centres, under a bishop. The monasteries, not the bishops and secular priests, were the main force of expansion of Christendom, and monasticism was a meritocracy in which the common man with no family or wealth could and often did rise. A monastery would be founded, normally outside the boundaries of town or city, and would inevitably attract local people who would naturally cluster around it as a centre of peace, stability and economic as well as for opportunities for social, cultural and spiritual growth.

We’ve talked before about the shift from Byzantine/Romanesque symbolism to the aesthetic and ultimately philosophical naturalism that started to be the obsession of the West about 1500. See, “Lies the Renaissance told you”

It is often in the manuscripts that the best preserved images can be found, since they were often safely stored, closed, and were not exposed to the destructive powers of sunlight, oxygen and humidity. And until more recent times, manuscripts, though often forgotten were rarely deliberately destroyed for the sake of changing artistic fashions. Unfortunately, the wall frescoes are almost all lost simply because tastes changed. Fragments of Romanesque frescoes are often uncovered from their Renaissance and Baroque overlays when old churches are renovated in Italy and Spain.

This is beautiful and I love the “damp fold” draperies. I’ve been learning quite a bit about symbolism in Byzantine icons and other art from Jonathan Pageau and, rather than being primitive, these pieces are highly sophisticated, speaking volumes through the symbols incorporated into each lovely piece.

I prefer Romanesque architecture to the Gothic. I find the former more masculine. As far as the art goes: because I was a number of years Orthodox, the Romanesque painting style is nicely reminiscent of Eastern iconography. All that said, I appreciate artistic diversity here in Latin Christianity. Sometimes the art and architecture of the East gets (aesthetically) monotonous.